|

Scientific Enlightenment Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.1. Chapter 3: The Origin of the Sacred, Animism, Taboo and Totemism ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.1. Chapter 3: The Origin of the Sacred, Animism, Taboo and Totemism ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

Copyright © 2004 - 5 by Lawrence C. Chin. All rights reserved.

We are now to elaborate on the origin of primitive religiousness in general, to see how its multivarious manifestations (not organized in an evolutionary succession but as different simultaneous manifestations) may have emerged from this common substratum by taking different directions. All the multivarious manifestations of primitive religiousness will be seen to derive from the thermodynamic anamnesic core of human religiousness.

The atheistic approach of such contemporary interesting theorists as Camilla Power, Chris Knight, and Nancy Jay (Throughout Your Generations Forever), just like that of the earlier "sociologists of religion" such as Peter Berger (The Sacred Canopy) or even Emile Durkheim, generally ignores and dismisses the experiential content of primitive religiousness by focusing solely on its sociological functions or rather "utilities" (aiding sexual selection, creating and cementing social solidarity, or ensuring patriliny) as if primitive people were fooling themselves in believing in gods and ancestor ghosts and the power of the totems (they were engaging in "collective deception", in the words of Chris Knight: "It is as if the gang of baboons all looked across the valley, saw no leopard -- but then joined in with their deceiver in pretending to see one." "Darwinism and Collective Representations", ibid., p. 334; collective self-deception achieved through heavy emotional involvement during ritual dance and enhanced by hallucinogens: "Cross culturally, ritual time tends to begin around dusk, when shadows lurk and the hold of reality fails. Trance-inducing dance, fasting and/or hallucinogens may enhance the effect. The whole point of all this is to make people see 'beyond' perceptible reality into the other-worldly domain -- that of morally authoritative intangibles. The gods and spirits, normally invisible, must be experienced at least periodically as more real than reality itself." And "[a] funeral occurs when a loved one has died. It is precisely that disturbing social absence which provokes counter-measures, the deceased's continued 'presence' being constructed by emotionally convincing display. If the illusory realm generated by ritual fails to eclipse 'this world', then something is wrong." "Sex and Language as Pretend-Play", The Evolution of Culture, p. 330; emphasis added). This contradicts my own experience, and my justification of their beliefs in terms of their "primitive" (functional) understanding of thermodynamics first resulted from reflection on my personal experience.

While growing up (Taiwan, 1970s) I had the bad habit of sticking my chopsticks into the rice of the rice bowl while taking a break from eating. My grandmother always shouted at me for this, saying one only did that when offering rice to the ghosts, "because ghosts didn't know how to use chopsticks". (The etiquette is to put the chopsticks on the table by the side of the rice bowl.) Once during the annual "Holiday of the Ghosts", when people customarily bought fake paper money especially manufactured for the use of the ghosts of deceased relatives, I was sent buying these too and watched my grandmother burn them in the yard (presumably the ghosts received the money in the form of smoke and used it for their daily "afterlife" expense). But that day my grandmother also put a bowl of rice with chopsticks stuck into the rice like I always did in the open yard in order to "feed" the ghost of something like a just deceased female relative that I had never met. I remembered staring at the rice bowl for some time, wanting to see how the ghost was going to eat the rice when no longer knowing how to use the sticks properly. (It seems that rice never vanished.) Some time later the light in our living room went on in the middle of the night while we were all sleeping upstairs. Next day I saw my grandmother murmuring on the sofa that the ghost was perhaps not appeased and more rice or money needed to be offered to her. I got deeply afraid then that without being well fed she would come in the middle of the night and harm me. (As people there always said -- and believed -- at that time: if you don't feed your deceased relatives or ancestors properly and don't give them enough money, they will get "hungry" and will come "eat you" in the middle of the night. The room in your house getting messy by itself when you are not even there or things mysteriously being mis-placed are the works of your dead relatives trying to warn you.) The point is that I at the time and all the people engaged in such practices really believed that the dead continued to exist in the immaterial, ghost form and that food needed to be offered to them (the original meaning of sacrifice: food for the ancestral spirits or gods) to prevent them from harming. This personal example is instructive because it was not embedded in an "official" ritual of the social collective as my grandparents, who were robotic, emotionless Mandarin government-military bureaucrats with little interests in local customs, performed the act purely out of personal belief. Nor did people in that increasingly modernized society do all these "rituals" in order to (unconsciously) cement social unity: the society was already being "secularized." This belief which was the only motivating factor left must be based on a certain human experience typically called "superstition" which, because it is basic to human thinking, repeats itself again in the less educated people even today when the ritual context ("culture", "custom") that it originally produced no longer exists to reinforce and legitimize its practice. (A famous pop-star in contemporary America hiring African witches to sacrifice small animals as a way to clear financial debt was considered only a "freak".) But precisely because of this such "superstition" can be isolated as the core experience whose extension (from the personal sphere), collectivization (as now the communal experience), systematization, and incorporation into social structures and functions readily produce what is observed as the primitive religiousness. Jay, Power, Knight, and the other sociologists have only focused on and explained the religiousness in terms of this incorporation into social structures and functions because they do not believe there is any "reality" behind the "ancestral ghosts", spirits, gods, and the like.

The personal instance just offered for example has already contained all the core ingredients of an ancestor sacrificial cult and only needs systematization, etc., to become such: the continued existence of the dead and their need to be fed or appeased just as the living. The offering to the dead can involve the slaughtering of animals or it may not. Thus "not all ritual killings are sacrifices, nor do all sacrifices involve slaughter. In some traditions, a plant may be substituted for an animal victim, and represent that victim..." (Jay, p. xxv.) The Huron for instance offered tobacco smoke to the sky-god and to certain large rocks thought to be the homes of powerful spirits. (Trigger, The Huron, 2nd ed., p. 107) Keeping in mind that the primordial experiential core of sacrifice is "feed for the ghosts" helps avoiding getting bogged down in superficial variations. (And also the "feed" frequently has to be in the form of smoke from burnt meat and plants in order to be congruent with the airy form of the breath-soul-spirit-god.) Naturally I wanted to know why I believed in ghosts when young. But then the more revealing question is why I stopped believing in ghosts later: because of the adoption of the structural perspective of modern science. The central theme of this work is that religiousness (and its superstitious core) is essentially the functional perspective doing thermodynamics with functional entities (consciousness objectified as "spirit" which gets identified as the energy of modern physics), which changes to a thermodynamics (conservation, transformation, dispersion) of structural entities (molecules, atoms, subatomic particles) when human consciousness starts taking grasp of the structural level of reality as the true reality.

When I first read about the two laws of thermodynamics I was struck by how common sense they were, that we had always already known them but were never aware that we knew them. The first law: energy can never be created or destroyed, but only transformed, this just means that nothing can come out of nothing, and nothing can ever disappear from something. Who knows not this? The second law as I first read about it in its manifestation as "the arrow of time": "Imagine a cup of water falling off a table and breaking into pieces on the floor. If you take a film of this, you can easily tell whether it is being run forward or backward. If you run it backward you will see the pieces suddenly gather themselves together off the floor and jump back to form a whole cup on the table. You can tell that the film is being run backward because this kind of behavior is never observed in ordinary life... it is forbidden by the second law of thermodynamics. This says that in any closed system disorder, or entropy, always increases with time... An intact cup on the table is a state of high order, but a broken cup on the floor is a disordered state. One can go readily from the cup on the table in the past to the broken cup on the floor in the future, but not the other way round." (Stephen Hawking, A Brief History of Time, p. 144 - 5) Similarly, we all know, even without ever hearing of the second law of thermodynamics in a physics class, that it never happens that, instead of being distributed evenly in the room, all the air suddenly moves to one corner of it, leaving us with nothing to breathe. Nor do we need to be reminded that when we put an ice cube into a glass of water, we will never see the ice cube get colder and the water get hotter. The reason for this, as I have already explained ("The Layered Structure of the Universe"), is that what we consider order is macroscopic order-formation that is not as complete or perfected an unity as is the microscopic, hence subatomic particles can go forward and backward in time (T of the CPT) but macroscopic objects cannot.

The common sense nature of thermodynamics, at least with respect to the first law, is documented in developmental psychology. Piaget for example made a division between the preoperational thought of preschool children and the operational thought afterwards, between which the acquisition of the understanding of conservation is precisely one chief determinant for the transition. "Conservation (the idea that amount is unaffected by changes in shape or placement) is not at all obvious to young [preschool] children... If they are shown two identical glasses containing equal amounts of lemonade, and then watch while the lemonade from one glass is poured into a taller, narrower glass, they will insist that the taller, narrower glass has more lemonade than the remaining original... [Similarly,] make two balls of clay of equal amount, and then ask a 4 year old child to roll one of them into a long skinny rope. When this is done, ask the child whether both pieces still have the same amount of clay. Almost always, 4-year-olds will say that the long piece has more." (Kathleen Berger, The Developing Person Through Childhood and Adolescence, 2nd ed., p. 290) The reason for this is, as Piaget explains, that preoperational thought is characterized by "centration", "the tendency to think about one idea at a time [in this case, the shape of the amount] to the exclusion of other ideas." (p. 289) But then, "older children, usually at around age 7 or 8 , understand the logical operation of 'reversibility', and realize that pouring the lemonade back into the shorter and wider glass, or rolling the clay back into a ball, would return things to their original state. Older children would also be able to arrive at these conclusions by applying the logical operation of 'identity' -- the idea that the content of an object remains the same despite changes in its shape." (p. 290 - 1) In other words, children are coming to grip with the first law of thermodynamics: nothing can ever disappear from something. This is foreshadowed earlier in the children's development by "object permanence" during the sensorimotor stage of cognitive development (8 - 12 months to 18 - 24 months), when they realize that what object slips out of sight, as when the toy rolls under the chair, continues to exist in some way, hence they search for it. Similarly, the moment when a child learns to ask where babies came from can be defined as the moment when s/he realizes that nothing can come out of nothing, hence that what exists must have come -- in fact continued -- from something else. We remark that the foundational stone of human religiousness is the belief in the continued (effective) existence of the breath-soul after death ("Synopsis of World Religions", and "Preliminaries on the Origin of Primitive Religion") and that such belief, as based on the anamnesis of conservation, is essentially like "object permanence", that the "person" after death must continue to exist in some form or another, and we search for and interact with it just as the child searches for the toy disappearing under the chair -- for ultimately nothing is ever created nor destroyed, but only transformed, so that out-of-sight does not mean cessation of existence -- the difference with the modern being that while we believe that the "person" continues to exist only as atoms, molecules, and ultimately the energy stored as these, the primitives believe, from the original human experience of breathing ("I breathe, therefore I think and metabolize": thence the compact identification of breathing-consciousness-living-animating: breath-soul as the "life-force"), that s/he continues to exist as conscious breath-soul-spirit (anima: this "life-force") which upon being exhaled from the dead blends into, and is, the whole atmosphere. The deities of natural phenomena and the therianthropic or theriomorphic ("totemic") spirit-gods on the one hand can then be hypostatized or metastasized from these ghosts of the dead floating in the atmosphere, and in fact frequently take precedence as the source for the latter; the whole atmosphere itself on the other hand can "animate" the whole of cosmos as the universal anima which in fact is where the breath-soul or life-force trapped ("reincarnated") in each of us and in every living being originally came from. "'There is indeed nothing in nature', writes Charlevoix, 'if we can believe the savages, which has not its spirit.'" (Cited in John Driscoll, "Totemism", Catholic Encyclopedia) Thus then animism, totemism, ancestor-cult, sacrifice (in both its communion and expiatory aspects: below) can all take off from here. The child's moment of awakening to conservation at the stage of operational thought is the ontogenic equivalent to the phylogenic moment when the Homo species realized that the dead must continue to exist as spirits. Things (and consciousness is taken as a thing!) don't just cease to exist when they disappear. It is not self-deception, but logic.

The path to the explication of sacrifice will yield up all those multivarious manifestations of primitive religiousness. Thus shall we begin. "We ordinarily interpret action with reference to the relation between means and ends so that if we know that a man is cutting wood to build a house, we believe we understand his action. We all agree that without the cutting of wood there is no building of wooden houses. But suppose we are told that 'without the shedding of blood there is no remission of sin' (Heb. 9:22)? How do we know whether the shedding of blood is or is not an indispensable means for remission of sin? And how do we recognize remission of sin when we see it?" (Jay, p. 1) Why is this Hebrew injunction today so mysterious? What if it is said "Without repayment there is no clearance of debt"? If we adopt the primitive understanding of thermodynamics we will immediately see that the remission of sin through the shedding of blood is as obvious as the cutting of wood for the building of house -- or the paying of debt for the clearance of debt owed.

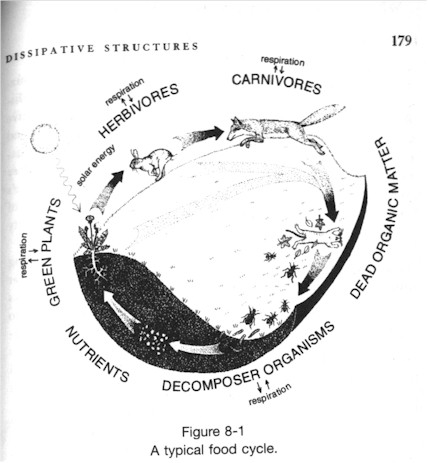

A house -- an order -- will not appear out of nowhere but can only come into being through the destruction, and the transformation, of some other order (the tree; the first law) -- and the total process of transformation (the order destroyed and the labour in-put to transform) necessarily involves loss of part of the order destroyed and energy input as waste (i.e. unrecoverable, un-transformable energy: the second law). The same with the destruction of the tree to keep order functioning -- such as burning fossil fuel (into which the primitive trees have been "condensed") to keep an automobile running. While the first law means that energy can never be created or destroyed but only transferred and transformed, "[t]he second law of thermodynamics states that energy conversions reduce the order of the universe. Put another way, energy changes, such as the conversion of chemical energy to kinetic energy, are accompanied by an increase in disorder, or randomness [or entropy]... Heat, which is random molecular motion, is one form of disorder. The more heat that is generated when one form of energy is converted to another, the more the entropy of the system increases." (Campbell, Mitchell, Reece, Biology, 2nd ed., p. 73) Life on earth appears and continues only because the sun is destroying itself, releasing part of itself to the earth in the form of energetic photons, which then get transformed into us or whose energy is converted to power us (i.e. their energy is used by the photosynthesizers to re-assemble ["recycle"] the pre-existent but disintegrated atoms into usable biomass containing the released solar energy in its chemical bonds now as chemical energy, which energy is then "harvested", that is, converted into kinetic energy, by herbivores and, through these, carnivores to power [animate!] themselves). But "the second law of thermodynamics tells us that the entropy of the universe as a whole is increasing; every energy transfer or transformation increases the entropy of the universe. For instance, about 75% of the chemical energy in the fuel tank of the car... will become disordered by being converted to heat. Moreover, all of the chemical energy converted to kinetic energy will eventually be transformed into heat: The organized energy of the car's forward and backward movement becomes heat when friction between the brakes and the wheels, and between the tires and the road, stops the car. Thus, even energy that performs useful work is finally converted to heat. All this disordered energy is added to the surroundings... Because of the second law of thermodynamics, a cell cannot transfer or transform energy with 100% efficiency. When a chemical reaction occurs in the cell, chemical energy is transferred between molecules; when light energy is trapped in photosynthesis, it is converted to chemical energy, when a flagellum moves, chemical energy is converted to the kinetic energy of movement. As any such transfer or energy conversion occurs, some energy always escapes from the system as heat. Cells do not have the machinary necessary to put the disordered molecular movement of heat energy to work, and even if they did, some of the heat would still be lost to the surroundings... the work of cells is powered by the potential energy contained in molecules." (Ibid.)1 A great ancestor has sacrificed himself, released part of himself (as the universal anima, the whole atmosphere) to get transformed into us (the reincarnation or re-materialization of this anima): the transmythological theme, to use Girard's characterization. The universal anima which is the substratum of all being, the result of the combination of the anamnesis of universal Conservation ("that there is never really any distinction or construction or dissolution but only re-shuffling and re-consolidating of the same underlying material here and now in this form and then and there in that form") with the particular experience of the conservation of the individual breath-soul which returns upon death to the "substratum" (atmosphere), thus takes precedence over the individual breath-souls as their source, and gives rise to "animism"2. This universal anima is literally taken to be the atmosphere, but, because the atmosphere is "above", can also be taken as the sky -- hence sky as the highest god.3 The universal Conservation implicit in the conservation of individual souls does not, for the primitive mind not yet concerned with logical consistency,4 mean that the conserved individual souls cease with their individualist identity. As the ancestral spirits that they are or as the ghosts or the natural-phenomenal or theriomorphic or therianthropic gods in which they have been hypostatized or metastasized, not only do they subsist as individuals in a variety of locales (in mountains, lakes, rivers, and, frequently artificially through our own effort, in "totem poles" or "charms") but they also visit us in dreams: dreams are taken as "visits" by external immaterial spirits because they seem independent of our consciousness, thoughts that "come to us" so to speak ("external consciousness" or anima). Our own breath-soul (the principle of our consciousness and metabolism) can go out and meet them, given our mastery of the necessary procedures for such "ecstasy" (c.f. Mircea Eliade in regard to the shaman.)5 The universal anima, as the substratum of all being, is precisely the primitive equivalent to the energy of modern physics, out of which all matter originally crystallized and to which all can be reduced given high enough temperature, according to the formula E = mc2. (Hence the Nuer designation of this anima, i.e. the divine, "kwoth, generally translated as 'spirit' by Evans-Pritchard", which Jay makes so much of [ibid., p. 14], is no mystery but common-sense: "Of kwoth itself, in a pure state, Nuer say they have neither experience nor knowledge; it is known only through its manifestations. These many manifestations differ widely from one another, but nevertheless, kwoth is believed to be one. Although kwoth is fully present in all of its manifestations, none of them can be said to be kwoth. For [Alasdair] MacIntyre [who thinks this makes no sense, is logically contradictory!], 'The difficulties in the notion of kwoth spring from the fact that kwoth is asserted both to be sharply contrasted with the material creation and to be widely present in it. It is both one and many; and the many, as aspects of kwoth, are one with each other.'" [Cited by Jay, ibid.] Jay, who does not understand religious experience any more than MacIntyre does, tries to make "intelligible" to us modern this "unintelligible" aspect of the foreign African thinking by comparing it with consciousness: "Of [consciousness] in a pure state (like the Nuer of kwoth) we have neither experience nor knowledge, for all consciousness is consciousness of something." [Ibid., p. 15] She consequently asserts that the core of religious experience, the sacred or the divine, is purely subjective, "what we have recognized is our own mind" (ibid.). Both are idiotic. In fact the divine is an objective phenomenon in the world that the primitives recognize by virtue of their anamnesis of Conservation. Think of the "cosmic dance" which Fritjof Capra makes much of ["Examination of the Parallels between Philosophy and Physics"], those endless mutual transformations of hadrons -- protons, neutrons, pions, etc. -- one into another because they are all just manifestations of the "one" energy. Metaphysicians of course would recognize in kwoth the mythic precursor of the Being of beings.) Literally energy, the universal anima thus not only materializes into everything or all the orders around us (e.g. the quoted reminder of Capra, "We tend to believe that plants grow out of the soil, but in fact most of their substance comes from the air"), but it also animates (as the kinetic energy of living beings!), energizes, and "revitalizes" these orders thus formed against their otherwise necessary tendency to disintegrate in accordance with "the arrow of time" (the second law) -- just as energy in the form of sun light re-energizes the biosphere everyday to stabilize all the biological orders therein (synthesized from atoms which ultimately came from the energy pool of the Big Bang) against their otherwise necessary entropic disintegration. As such this anima is the sacred or the mana.6 But too much concentration of its ability (power) to revitalize can also destroy, just as sunlight can also burn and kill during prolonged exposure to it or when concentrated by a magnifying glass. Hence the sacred, the mana, the power of this universal anima, has to be regulated in its use with special insulating rules (règles) constituting a system of taboo.7 Just like the un-equal distribution of matter-energy in the Universe, concentrated in galaxies and especially in stars -- which is caused by gravity and which, by the way, allows work to be done and orders formed -- the anima as mana is unequally distributed in the cosmos but is especially concentrated in certain localities (places or large rocks), objects, and some people (chiefs, shamans, and priests) -- and such unequal distribution, by the way, also allows work to be done and orders formed, because mana "could be transferred from one object or person to another", but only from its more concentrated region to its less concentrated region in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics, just like sunlight and electricity:8 "The fluidity of mana made it a kind of physical energy [it precisely is the primitive equivalent of it!]... the transfer could be affected by touching one mana-charged object with another with less mana; in particular, a person of high mana could infuse an object with some of his or her mana by handling it." (Alan Miller, ibid., p. 469 - 70) As we shall see shortly, the whole of primitive religiousness consists essentially in properly directing the flow of this anima-mana to do work and to thus maintain the order of the social organism.

The local concentrations of mana can be coincidental with the continued subsistence of the individual animae in different locales, mentioned earlier. Also, Miller makes the point (following Marett) that such local concentrations are usually identified in unfamiliar or uncanny objects and places (ibid., p. 469), but it is unclear whether it is their uncanniness which makes them suspect of high concentration of mana or the other way round.

Note that although taboo designates the negative aspect of mana, it is not to be confused with "evil", with that dissolutive force whose symbolization is conditioned by our experience of the linear aspect of entropy-increase or arrow of time. Taboo is rather the experience of the good god's capability also for harm if it be not properly handled.

Mana being the term the Polynesians used to designate the energetic universal substratum of all being -- this universal anima which is by the functional perspective taken simply as the atmosphere, and remember mana itself originally means "breath" -- other peoples have of course used different terms to name the same: in America the Huron used orenda, the Lakota, wakan, the Algonquin, manitou (Miller, ibid., p. 470; the Indo-European examples below); Egyptians called it maat, which was already quite beyond mana in connotation, in fact pre-philosophical, in accordance with their cosmological mode of existence, no longer tribal. Since that which is essential to the maintenance of life, i.e. food, whether as plants or animals, is produced by the atmosphere, nourished by it, and in fact is the concrete, tangible manifestation of this non-tangible energetic substratum of all being, universally the word to designate the primordial human experience of the "sacred" is frequently also the word for "food" or "nourishment" (i.e. restaurant): consider brahma and maat again, the Greek nomos and the Chinese Di.9 We will see more of the significance of this later when studying the meaning of sacrifice. Then there were the Indic rta, the Chinese Dao, the Presocratic arche, which had differentiated this original experience of the substratum into a philosophical concept properly speaking, as we shall see so much later. The progressive differentiation of this primordial substratum from mana through maat to Dao caused the gradual loss -- but never completely (except perhaps in Anaximander's apeiron) -- of its original concrete reference to the atmosphere, and by the time of the maturation of the structural perspective in the first part of the twentieth century it becomes "energy" with a quantitative meaning only. The contemporary New Age spirituality, for example, uses correctly the "energy" of physics to denote that original universal anima from which we all came. That the budding functional perspective of the primitive time could concoct a concept in such proper metaphorism of the modern "energy" as mana or manitou clearly are is explained by the fact that the primitive concept came from the anamnesis of Conservation while the modern results from the verification of this first law of thermodynamics (if there is never really any construction or dissolution but only re-shuffling and re-consolidating of the same underlying material here and now in this form and then and there in that form, then where did all these individual quarks and leptons that make up matter today originally come from? Differentiated from the pool of undifferentiated energy right after the Big Bang and at the beginning the radiation era. C.f. later.)

The anamnesis of Conservation underlies in fact what Rudolf Otto has designated as the experience of the "holy" (das Heilige), or the "numinous", in any case the sine qua non of religion. The development of this "ideogram" called the "numinous" into concepts of gods and spirits, which he calls "schematization", is here equivalent to the progressive differentiation-clarification of the anamnesis of Conservation. (Das Heilige, 1917, C.f. Miller, p. 470 -1) In other words, while in such traditional thinking as Otto's the experience of the sacred is given without explanation, I provide the foundation for this experience in the external reality, in the very thermodynamic structure of the cosmos, i.e. conservation of energy despite its endless transformations in accordance with the second law -- and this thermodynamic structure, together with gravity and that portion of electromagnetism called light, and unlike the atomic structure of matter and other forces, is immediately given to consciousness to understand -- so that human religious experience can be rendered simply common sense, not something mysterious. Similarly, Otto's opposition of the fundamental religious feelings mysterium tremendum and mysterium fascinans expresses the same "dichotomy of mana and taboo, the positive and negative aspects of the sacred power" (ibid., 471) His description of the effects of tremendum "by the ideogram of 'creature consciousness', the elementary feeling articulated by the thought of having been created, assembled, as it were, as a kind of contingent and therefore somewhat arbitrary and temporary configuration with no intrinsic merit or value or power" really just reflects the understanding of the status of individuality within the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos, "the necessary and eternal continuation, never increasing nor decreasing, of a 'Total' (the Underlying, the substratum: the law of conservation of energy) despite the constant formation and dissolution within this Total of the many individuals (which form and de-form, according to the second law of thermodynamics, from and back into the energy-substratum)" (as stated in the Synopsis). The radical opposition between the eternal Total and the temporal individual however causes him and many primitives to mischaracterize the sacred as radical otherness (das ganz Andere; ibid.). The self, in fact, is just an temporary aspect of the sacred. The mischaracterization reaches the maximum within the first mode of salvation in the radical otherness of the Yahweh of the prophets; but in the second mode the identity between the self and the sacred is restored, as in the formula Atman = Brahman.

The thinking about the experience of the sacred along this line is recently somewhat taken up by Georges Bataille, and our thermodynamic interpretation seems simply to be reformulating his opposition between the sacred and the profane in thermodynamic terms. E.g. Guy Ménard ("Le sacré et le profane, d'hier à demain", in Figures contemporaines du sacré, 1986) summarizes: "Le sacré, pour Bataille, c'est essentiellement - et, en un sens, très simplement - le bouillonnement prodigieux, le déchaînement exubérant, aveugle et violent de la vie sous toutes ses formes; déchaînement que l'ordre des choses, pour durer, doit de quelque manière enchaîner, endiguer. Se trouve par là-même définie, en contrepartie, la sphère du profane: le profane, dans cette perspective, ce sont justement ces 'digues' qui viennent enchaîner, harnacher le prodigieux déchaînement de la vie, et sans lesquelles la vie humaine (en tant qu'humaine) serait impossible." ("The sacred, for Bataille, is essentially... the prodigious bubbling, the exuberant, blind, and violent outburst of life [force, energy, the anima-mana] in all its forms; an outburst which the order of things, in order to persist, must in some way chain up and contain in dykes [i.e. though an order must have energy in-put to persist against the general tendency of nature toward entropy-increase, it must at the same time in-put this energy with caution and moderation: although all the biospheric orders cannot sustain their order against their tendency to reach equilibrium with the environment without the sun shining on them, excessive exposure or proximity to the sun would destroy them as well.]. Against that, as the counterpart, is defined the sphere of the profane [the order itself and its self-maintaining strategies]: the profane, in this perspective, is just these dykes which come to chain up and harness the prodigious outburst of life [energy, anima-mana], and without which human life would be impossible." The profane, as to be seen, is just the social organism with all its internal pathways and intercourses (the "dykes"), i.e. society conceived by the primitive as an organism.

"Ce faisant, l'humanité endigue cela-même qui devient - ainsi - le sacré: elle pose le sacré dans le mouvement même où elle s'en sépare. Elle enferme pour ainsi dire le sacré dans ce qu'on appellera des interdits... Au sens strict, elle interdit le sacré [taboo]. À prime abord, cette manière de voir peut paraître paradoxale. On voit cependant qu'il en est bien ainsi, que c'est bel et bien le sacré qui est interdit. Et cela se comprend: laisser libre cours au sacré, à l'exubérance aveugle et violente de la vie, comme les animaux ou les forces de la nature qui ne connaissent pas d'interdits (et que les humains, de ce fait, ont souvent considérés comme particulièrement sacrés, totalement dans le sacré [i.e. the raw, total manifestation of the anima, before its entrapment in the particularly regulated order of the human social sphere]), équivaudrait en effet à dissoudre l'humain dans la nature inconsciente, à retourner au 'grand tout' de la continutié cosmique [i.e. the dissolution of order back into the conserved equilibrium-substrate of being, or the order reaching equilibrium with the environment]. Laisser libre cours au sacré, pour l'humanité, ce serait au fond courir tout droit à la mort (en tant qu'humanité), un peu comme ces insectes fascinés par la flamme, et qui s'y précipitent... (On comprend bien sûr, et de ce fait, le caractère profondément sacré de la mort elle-même, dans la mesure où celle-ci est perçue comme ce qui fait précisément retourner les humains à la continuité du cosmos [the return of the individual, personal anima back to the atmospheric total anima].)"

"Mais on le sait bien: si l'ordre - profane - des choses, fondé sur la conscience, la raison, le travail et les interdits [i.e. order], permet l'existence de la vie humaine en tant que telle, il est lui aussi, à sa manière, porteur de mort. Plus exactement: si le profane est bien ce qui rend la vie humaine possible, il n'est pas lui-même porteur et source de vie [order needs energy input from the energy-substratum of being!]. Il s'agit bien plutôt d'une digue, d'un barrage, d'un frein [order as the enclosure of raw, formless energy into orderly form]. Avec le temps, l'ordre profane se fatigue, se sclérose, s'ankylose, se vide de sa substance (comme on pourrait également le dire d'une pile rechargeable...)" That is, given the second law of thermodynamics, or within the thermodynamic force field, order will collapse back into equilibrium unless energy be pumped in. For life, and the social community in the case of the primitives, these orders being open dissipative structures, are precisely systems that are constrained away from equilibrium and that pay what they owe to the second law by building internal kinetic pathways that send things in their environment, i.e. other orders, instead of themselves, to thermodynamic equilibrium. "Constamment, il a besoin d'être revivifié, régénéré, rajeuni, de se rebrancher - ou de se recharger - sur cet inépuisable réservoir qu'est l'exubérance cosmique de la vie. C'est-à-dire, en somme, sur le sacré." But the reservoir of energy itself, the sacred, has to be another order.

"Constamment, la vie humaine a besoin de lever les interdits qui endiguent le sacré, de les transgresser. La transgression apparaît bien en ce sens à la fois comme l'opposé de l'interdit et comme son complément indispensable. Insistons: la transgression n'est pas la négation, le refus ou l'abolition de l'interdit... mais plutôt sa suspension temporaire, ponctuelle. La transgression affirme à la fois la nécessité de l'interdit (sans lequel il n'y aurait pas de vie humaine possible) et la nécessité de son dépassement périodique (sans lequel la vie humaine se scléroserait)." The energy to be in-put must be ordinarily tabooed to avoid excessive exposure to it or infusion of it (like chocking oneself to death with food, as those who were just liberated from concentration camps or POW camps but were on the verge of starving to death were apt to do when suddenly provided with total access to food); but then it must periodically and cautiously be let in to sustain order against collapsing back into equilibrium. Religiousness then is precisely this process of restrictive and regulative feeding to the social organism of the energy-substratum which is otherwise too energetic as to be destructive: "'La liturgie et les rites des religions positives', suggère à cet égard Franco Ferrarotti au moyen d'une image saisissante, 'c'est la combinaison d'amiante qui permet d'accéder au sacré sans être réduit en cendres...'" (Ménard explains the same idea of the sacred in a different context in his more recent Petit traité de la vrai religion, Liber, Montréal, 1999; esp. Ch. 5, "Le sacré: interdit et transgression".) This will be the guiding principle for understanding the totemic sacrifice.10

Animism can through emphasis on different aspects of the anima-mana on the one hand lead to totemism and on the other to shamanism and deity-cults in general (I share thus Driscoll's view: "The basis of Totemism is the animistic conception of nature. The life revealed in living things, the forces manifested by physical objects are ascribed to spirits animating them or dwelling therein." Ibid.), and all these lead to sacrifice. Totemism (known mostly from the North Native Americans and the Australian aborigines) is thus not to be regarded as more primitive than any other pre-salvational (i.e. before the testamental religions and philosophy) religiousnesses but is on equal footing with these others. (Full clarification, later.) Animals differ from the rest of the natural phenomena in that they are "more" animated (obviously, since they are living: they are animae par excellence) and yet they belong to the rest of nature because of their constancy across space and through time: of one species every member looks like every other and the offspring look exactly like the progenitors. The lack of individuality in the animal species confers upon them a constancy that is more akin to nature than to human. And yet their animatedness stands out and seems thus to be the most suitable local concentration of the anima-mana into which the breath-soul of ancestors have blended: animals as a de-individualized whole are the "omphalos" in the whole scheme of the animation of the cosmos as a whole by the ancestral anima-mana. But if the ancestral anima is most concentrated in the animals, particular species among them can furthermore be singled out as the most concentration of anima-mana in all the localities in the whole of cosmos (the omphalos within the omphalos). That species is thus the totem animal: those animals are the anima of our ancestors and hence are our ancestors. Such derivation of the totem animal from the concentration of anima-mana does not exclude the identification of totem in plants and in other inanimate objects.

Thus follows the most important of the "catechism" of a totemistic world-view: a species of animals is the ancestor of our clan, it thus "protects and gives warning to the members of its clan", and furthermore "[t]he totem animal foretells the future to the loyal members of its clan and serves them as guide" (Freud, Totem and Taboo, trans. Strachey, p. 127)). "The clan totem is reverenced by a body of men and women who call themselves by the name of the totem, believe themselves to be of one blood, descendants of a common ancestor, and are bound together by common obligation to each other and by a common faith in the totem." (Frazer, cited by Freud, p. 129) Thus "Tylor says every Indian looked for and found hospitality in a hut where he saw his own totem figured and, if he was taken captive in war, his clansmen would ransom him (Jour. Anth. Inst., XXVIII). Morgan shows the superiority of the totem bond over the tribal bond among the Iroquois. In the Torres Straits warfare could not affect the friendship of the totem-brethren." (Driscoll) Since the ancestral anima animates the species as a whole ("As distinguished from a fetish, a totem is never an isolated individual, but always a class of objects, generally a species of animals or of plants..." Frazer, ibid.) it also animates ("reincarnates", so to speak) its clan descendants as a whole -- and the "reincarnation" of the ancestral anima in the clan as a whole which regenerates it at the same time against entropic disintegration is precisely the meaning of totemic sacrifice, as shall be seen. (The solidarity of the group produced by the totemic belief is a sociological function whose relationship with the two others, exogamy and patriliny-matriliny, shall be considered later.) Finally, "the man shows his respect for the totem in various ways, by not killing it if it be an animal, and not cutting or gathering it if it be a plant." (Frazer, ibid.) In fact, "the totem is generally taboo to the members of the clan. They could not kill it or eat its flesh." (Driscoll, ibid.) Thence also the totemic animal "which has died an accidental death is mourned over and buried with the same honours as members of the clan", and when the totemic animal "has to be killed under the stress of necessity, apologies are offered to it and an attempt is made by means of various artifices and evasions to mitigate the violation of the taboo -- that is to say, of the murder." (Freud, p. 126 - 7) The guilt generated by the necessary killing of the "ancestor" plays an important role later in the formation of the duality of communion-expiation taken on by sacrifice. Keeping in mind that it is the ancestral anima residing within and animating the animals that calls for the taboo helps avoiding distraction by exceptions: "Hill-Tout says the Salish tribes considered the real sulia [the ancestor spirit coming frequently to visit in dreams (ulia)] to be a spirit or mystery-being, though it might take the form of an animal and it could not be killed or hurt if the animal were slain, hence the hunter did not respect the life of the totem; in fact he was considered more successful in hunting his sulia animals than other men." The ancestor-nature looks after us by offering himself as the substance for our regeneration of ourselves (against entropic degeneration): this meaning is again to play an important role in totemic sacrifice later. Hence similarly "[t]he Melanesian is supposed to have peculiar success in hunting his totem animal." (Driscoll) What is important to note here is that what is ordinarily strictly tabooed -- the killing of the totem animals during ordinary occasions by individuals for his or her own purpose -- is to be ritually, periodically, and collectively performed: the sacrifice and eating of the totemic animal at solemn totemic festivals.

Recall that the nature of an open dissipative structure -- in this case, it is the social organism, the clan itself -- is to send some other orders -- the energy input -- to thermodynamic equilibrium (i.e. destruction) instead of itself so as to maintain itself, to revitalize itself against entropic disintegration. But this other order -- the totemic animal, i.e. the ancestral anima -- cannot be just taken in anytime by anyone but only periodically and collectively, with everyone participating at once, and then only carefully with predetermined procedures -- otherwise the social organism may choke itself to death or burn itself dead. This is the meaning of the ordinary totemic taboo and the extra-ordinary totemic sacrifice. This is what is described by William Robertson Smith.11 "A sacrifice of this kind was a public ceremony, a festival celebrated by the whole clan. Religion in general was an affair of the community and religious duty was a part of social obligation. Everywhere a sacrifice involves a feast and a feast cannot be celebrated without a sacrifice. The sacrificial feast was an occasion on which individuals rose joyously above their own interests and stressed the mutual dependence existing between one another and their god [i.e. the ancestral anima]." (Freud, ibid., p. 166) Feasting together was for the primitives the most effective way to cement a group of people together as kin, and thus to maintain social order. "'A kin was a group of persons whose lives were so bound up together, in what must be called a physical unity, that they could be treated as parts of one common life [of a single organism]... In a case of homicide Arabian tribesmen do not say, "The blood of M. or N. has been spilt", naming the man; they say, "Our blood has been spilt". In Hebrew the phrase by which one claims kinship is "I am your bone and your flesh".' Thus kinship implies participation in a common substance. It is therefore natural that it is not merely based on the fact that a man is a part of his mother's substance, having been born of her and having been nourished by her milk, but that it can be strengthened by food which a man eats later and with which his body is renewed." (Smith, & Freud, ibid., p. 167; emphasis added.) By eating the totem animal together and at the same time, the group establishes itself as a single organism participating in the same substance (i.e. the ancestral anima) which runs through all of them. The ancestral anima has reincarnated itself in the whole group and as the single group. "Anyone who has eaten the smallest morsel of food with one of these Bedouin or has swallowed a mouthful of his milk need no longer fear him as an enemy but may feel secure in his protection and help. Not, however, for an unlimited time; strictly speaking, only so long as the food which has been eaten in common remains in the body." (Ibid.) That is, because of the second law, and because of our nature as open dissipative structure, the ancestral anima we have in common in us would eventually dissipate in time, and then social order (group solidarity) would collapse. Hence the incorporation of the ancestral anima again, to revitalize the social organism, just as an organism has to eat repeatedly or periodically or else would collapse into equilibrium with the environment.

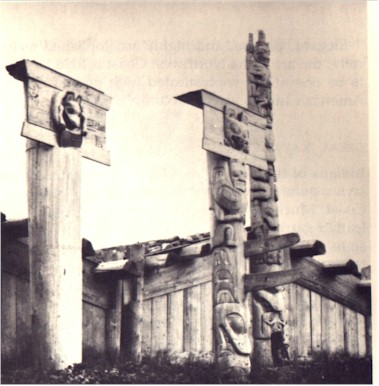

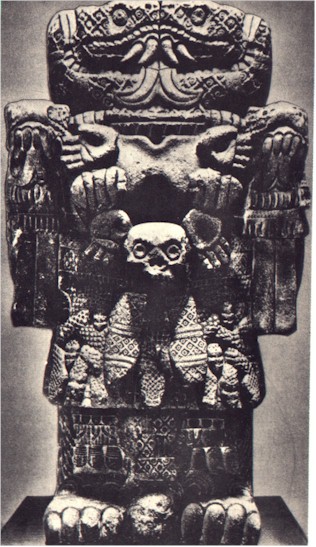

The periodic ritual of the sacrifice and feast of the totemic animal is therefore the occasion for the reincarnation of the ancestral anima in the social organism. "On [these] particular solemn occasions and at religious ceremonies the skins of certain animals are worn. Where totemism is still in force, they are the totem animals." (Freud, p. 127) Becoming the totemic animal signifies this reincarnation. So then is the meaning of such acts as: "dressing in the skin or other parts of the totem animal, wearing badges, masks, crest-hats of the totem, arranging hair, painting face or body, tattooing and mutilating the body so as to resemble the totem ; so also totems are painted or carved on weapons, canoes, huts, etc. From this custom we have the totem poles decorated with crests of clan and personal totems, and with red crosses representing the ghosts of their vanquished foes, who are to be their slaves in the other world." (Driscoll, ibid.) The globality and inaccessibility of the ancestral anima-mana is remedied by its localization ("entrapment") in an artificially constructed totem pole (artificial local concentration), which in this way is no different from the Asherah in Yahwism or from the wooden pole of the ancestor-king that King Wu made of his father (the problem of Asherah, later) -- or from any of the statues of gods for that matter: it depends on whether the anima is to manifest as totem animals, as gods, or directly as ancestors. (compare the various totemic poles below with Coatlicue).

| "Totem pole in Stanley Park, Vancouver, Canada. Totem poles are carved and painted logs, placed upright, made by Indians of northwest USA and Canada. The poles are decorated according to the function of the pole – for instance, it can serve as a grave marker, or depict a family legend... In declaring the totem animal, totem poles often also announced the status, wealth, and family history of the owners." (From Tiscali Reference) |

|  |

| Ancestral poles, Asmat, New Guinea, 1960, wood. "The fact that remote spirits and ancestors are portrayed partially accounts for the lack of naturalism... The Asmat pole is erected in ceremonies that prepare the participants to avenge the death of a community member in war [localize the ancestral anima to energize and consolidate the group before the battle]. Such poles represent ancestors; the openwork 'flags' are penises, exaggerated in a reflection of the Asmat male's aggressive roles in sex and head-hunting." (Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 8th ed. p. 516 - 7) | Haida mortuary poles and house frontal poles at Skedans village, British Columbia, 1878. "[These], used where totemic crest emblems of clan groups are displayed before the clan chief's house, are striking expressions of this interest in social status." (Ibid., p. 501) |

Coatlicue, goddess of earth and death [the dissolutive power, evil!], Aztec, fifteenth century. Andesite, approx. 8"6 high. (Ibid.)

At this point our analysis has to diverge into two different directions: the problem of the relationship between group solidarity and taboo and the necessary engenderment of expiation from the totemic sacrifice.

First, it seems that taboo is doubly determined, not just by the need to prevent over-exposure to the energetic ancestral anima-mana (while some exposure to it is necessary to maintain order), but also by the pragmatic need for group solidarity which the regulated exposure itself establishes. The use of ritual to establish group solidarity has been present since the very beginning, i.e. even the first ritual of sham menstruation of the coalition of women probably involved the subordination of the interests of the individual women to that of the group. (Here we continue with our narrative of Camilla Power and Chris Knight's theories ["The Origin of the Sexual Division of Labor"].) Power for example cites (from A.I. Richards) the view of men of the matrilineal, uxorilocal Bemba "on why the female puberty rite, chisunga, had to be performed": "No one would want to marry a girl who had not had her chisunga danced. She would not know what her fellow women knew. She would not be invited to other chisunga feasts. She would just be a piece of rubbish; an uncultivated weed; an unfired pot; a fool; or just 'not a woman'." She continues: "Until the final stage when the bridegroom arrived, men were respectful onlookers, averting their eyes as the chisunga procession passed their huts... The celebrants were women, observing a strict, ritually rehearsed hierarchy under the authority of the mistress of ceremonies (nacimbusa)... Candidates were expected to be humble at all times, even when subjected to torment and abuse... An elderly woman, often of royal lineage, who was proven as a midwife and had special ritual knowledge, the nacimbusa, made the chisunga through her energy and charisma; she worked 'magic of attraction' by attention to costly detail. Particularly important was a series of pottery models -- sacred emblems (mbusa) -- which were time-consuming and elaborate in construction, yet destroyed or discarded once they had been used for specific ritual actions... Throughout the ceremony, a three-week event in 1931, the primary cosmetic material was red camwood powder mixed with oil as a paint that made vivid crimson splashes... On four climatic occasions, the candidates and the main actors were daubed in this mixture..." ("Beauty Magic: The Origin of Art", The Evolution of Culture, ed. Robin Dunbar, Chris Knight, and Camilla Power, p. 92) The red colour is used of course to advertise "imminent fertility of the initiate, but the cosmetics also provide mechanisms for marking reciprocal relations and obligations among the women. These costly, lengthy, often traumatic rituals appear to be critical in mate choice; girls who failed to undergo initiation were traditionally unmarriageable -- 'fools' or 'weeds'. Much of the most elaborate art belonging to these cultures was produced either in the context of, or with reference to, female initiation." (p. 93) Remember that sham menstruation dance (masquerading as animals, as male, and as menstruating) as saying No to male sexual advance (unless he "brought home meat") would not work unless all women did it together -- simultaneously all saying No -- otherwise the man who was refused sexual access would simply go to another imminently fertile woman. "Within any coalition, the strategy [of cosmetic manipulation of menstrual signal] is well-designed for a reciprocal altruistic alliance, since any female must prove her commitment to the alliance when she is cycling before she can derive any benefits when she is not cycling." (p. 99) Any female who did not participate in the sham menstruation dance-procession would be a threat to the attempt of the coalition of women to establish the sexual division of labour to force men to provide meat for child-rearing women; hence the coalition of women would force her to, and hence the coercive and traumatic nature of these female initiations for the initiate, who was basically forced to learn that, from now on, she must "blend into the group", both for her welfare and for that of every other woman (no woman could get free meat from men unless all women get meat from them at the same time). Initiation ritual is for the initiation into the group. But this female initiation also advertised another, positive incentive for the men bent on mating: "Suppose a young female reaches puberty. At the time of her first menstruation, a cosmetic ritual should be staged, involving immediate coalition members in costly preparations, gathering and processing pigment, followed by energetic performance. Not only does such ritual advertise a female of maximum reproductive value; it also demonstrates in ways that are 'hard to fake' and 'easy to judge' the extent of the female's kinship support network and its ability to organize coalitionary alliances... [T]he species-specific adaptation which human cosmetic ritual advertises is the ability to form and deploy coalitionary alliances." That is, for the "choosy" men who have meat to invest, the dance-procession signals "Invest in me [i.e. choose me], because I have extensive kinship support, and my children will have it.'" (p. 101)

The first taboo is therefore the (even fake) menstrual blood of the imminently fertile women, who cannot be touched, who even have to be secluded, made inaccessible, even to the extent that the taboo on sex during pregnancy and the postpartum period can be assured by painting oneself "with red cosmetics believed to afford magical protection. Body paint functions, in effect, as an anti-rape device." (p. 106)12 We have already seen that by metaphorical magic the theriomorphic women become identified with the hunted animals, and her menstrual blood becomes the blood of these animals, so that the bleeding game animal similarly becomes tabooed, not to be touched, thus preventing the hunting men from devouring it himself and not bringing it home to the women. This of course broadens the solidarity formerly assured of the coalition of women to include now the whole tribe: now all men and women have to work together: men hunt, women cook and raise children. This is the first inkling of the taboo related to the sacred, and is more sociological than experiential: if the taboo on the bloody, raw meat be violated (eaten individually by the hunter in his selfishness), then the new social order just established -- the sexual division of labour -- would collapse. The energy of the sacred (of meat) can only be released after being "cooked" through women's labour: the removal of the taboo. All people must eat together as a group. The taboo on blood has thus established social solidarity and order, coercing the individuals to conform to the welfare of the whole group.

(Later we will see how men develop rituals (especially those relating to the ancestors, whether in terms of sacrifice or initiation) also to ensure the solidarity of the coalition of men particularly excluding women; and that it is precisely the rituals of men which typically predominate in even primitive societies.)

Similarly, the killing of the totemic animal by private persons during private occasions to release the ancestral ghost is tabooed not only because it is an imprudent act that is dangerous in its possible impropriety in handling the energetic mana frequently too exuberant as to be destructive (the experiential justification), but also because it is a selfish act which threatens the solidarity of the clan, amounts to a betrayal of the group, and thus cannot be tolerated: just like the taboo on incest. The sociological function of taboo is essentially the prevention of "freeriders" ("those who take the benefits that derive from social contracts while allowing everyone else to pay the cost", e.g. "who take the benefit but do not repay the gift", Robin Dunbar, "Culture, Honesty, and the Freerider Problem", The Evolution of Culture, p. 194, 196) For the private persons, there are always the "personal totems" to resort to (below). "As we have heard, there is no gathering of a clan without an animal sacrifice, nor... any slaughter of an animal except upon these ceremonial occasions." (Freud, ibid., p. 168) All people must release the ancestral anima-mana as a group. Religiousness, as we shall see in more and more details, is all about metabolism, and the unit of metabolism is no longer the organism as in the biosphere below but society and the cosmos. The communion sacrificial feast is the eating by the society projected as an organism (supraorganism: Corm): the eating is necessary because the order of the community (its low entropy) can only be maintained against entropic disintegration via the incorporation or reincarnation of the ancestral anima-mana concentrated in the totemic animal. All individuals must eat together at the same time during the communion feast in order to signify that it is the society that is eating, not individual persons. Anyone who does not participate is someone who derives benefits from living in the group but avoids the corresponding responsibility: a parasite. But the killing of the sacrificial animal to release this anima-mana is a sorrowful act, for, remember, the nature of an open dissipative structure (in this case, society) is that it maintains itself by destroying another order and sending the latter to equilibrium instead of itself. Now the ancestor has sacrificed itself, released its energy to regenerate us as a group, and thus restored us from the disorder into which we've fallen -- it itself has gone into that disorder.13 Recall that the word for "sacrificial food" and for "god" or "divinity" is frequently the same: god is food. This is really how the big question posed by Benveniste should be answered: "Pourquoi 'sacrifier' veut-il dire en fait 'mettre à mort' quand il signifie proprement 'rendre sacré' [sacrificare, sacrificium]? Pourquoi le sacrifice comporte-t-il nécessairement une mise à mort?" ("Sacré", Le vocabulaire des institutions indo-européennes, II, p. 188) Because of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos only through the destruction of another order can the energy needed be procured for regeneration: not the secondary function given by Mauss and Hubert of communication with the ancestor. The primitives have always known, as we know today, that energy is the substratum of all being, that matter (physical materiality) is really just energy in concentrated form -- the difference is that they have thought that this energy is "air" (spirit, wind) but we know it only to be an abstract quantity. Since energy is "trapped" in matter, the only way to release it is to destroy the matter. This necessity confers upon the primitive consciousness quite a different attitude toward death: thus Festus' statement is to be interpreted differently than by Benveniste: "homo sacer is est quem populus iudicauit ob maleficium; neque fas est eum immolari, sed qui occidit parricidi non damnatur." ("The person designated sacer is one whom the people judge as 'impure' [so far the Latin concept conforms to the double meaning of the sacred, of mana, as desirable but tabooed at the same time]; neither is it permitted for him to be killed, but whoever kills him is not to be condemned as having committed patricide [or murder]." Ibid., p. 189) Why? Because we kill the sacred animal-ancestor not out of malice, but out of necessity, and we are consequently not guilty of murder. Thus, though so dangerous as the sacred person is -- being too "energetic" -- such that he should not be touched, there are times when the sacred has to be killed to release the energy. Benveniste notes that the two Latin words for "sacred", sacer and sanctus, both came from the same root *sak-. The two words do not have the same meaning: "Pour sanctus nous avons une définition dans le Digeste I, 8, 8: sanctum est quod ab iniuria hominum defensum atque munitum est: 'est sanctum ce qui est défendu et protégé de l'atteinte des hommes', cf. Digeste I, 8, 9-3: proprie dicimus sancta quae neque sacra, neque profana sunt, sed sanctione quadam confirmata, ut leges sanctae sunt...; quod enim sanctione quadam subnixum est, id sanctum est, et si deo non sit consecratum": "Therefore we call 'sancta' those which are neither 'sacra' nor 'profana', but confirmed by 'sanction', such as, laws are 'sanctae'...; what is thus supported by 'sanction', is 'sanctum', and it is not to be consecrated to gods." "Sanctum" is thus not the sacred, not godliness itself, and hence not the sacrificial food -- not the restaurant. It is, rather, as Benveniste analyzes the matter, the boundary which protects the sacred, i.e. the rules of taboo. "On dit: uia sacra, mons sacer, dies sacra, mais toujours: murus sanctus, lex sancta. Ce qui est sanctus, c'est le mur, mais non pas le domaine que le mur enceint, qui est dit sacer" (p. 190). On the other hand, "qui legem uiolauit, sacer esto", "he who violates the laws [the taboos], that's the sacer"; i.e. the sacred itself -- and for example the priest embodying it -- can and in fact has to, for the sake of the continual existence of the community, violate the "sanctions", kill the sacer, and release the energy therein trapped. "Il n'y a pas de sanction pour celui qui, touchant le sacer, devient lui-même sacer... on ne le châtie pas [for he did the necessary], ni non plus celui qui le tue [he, 'contaminated with', i.e. having acquired the energy of, the sacred, has to periodically be killed too]." But by the killing of the ancestor we have then owed the ancestor, for, as he has himself paid the debt we as order owe to the second law, this debt still persists as that we now owe to our ancestor. The atmospheric environment, which is the ancestor, has become more disordered in order for us to persist as order. The debt is the order of the ancestor transferred onto us. This debt of ours necessarily exists no matter how we defer it (i.e. through the ancestor), simply because of the second law: there can be no such thing as a perpetual motion machine; energy has to come in, and we have to eat, and so does the social organism; and in the process more disorder is created in the surroundings. "We have heard how in later times, whenever food is eaten in common, the participation in the same substance establishes a sacred bond between those who consume it when it has entered their bodies. In ancient times this result seems only to have been effected by participation in the substance of a sacrosanct victim. The holy mystery of sacrificial death is 'justified by the consideration that only in this way can the sacred cement be procured which creates or keeps alive a living bond of union between the worshippers and their god.'" (Ibid., p. 170 - 1) This bond is the order of the social organism. But debt is guilt. Hence "when the animal is made the victim of a ritual sacrifice, it is solemnly bewailed" (p. 127). The communion aspect of sacrifice must thus necessarily be accompanied by another expiatory aspect. With this we arrive at the "logic of sacrifice" as described by Nancy Jay. (The ceremony for the "multiplication of the totem species" [intichiuma among the Arunta] similarly belongs to the expiatory side rather than to the communion.)14 We can also see that totemism is not a particularly distinctive religious mode apart from shamanism, ancestor cult, or deity-cultic practices in general, but forms with these a spectrum, whose variations from one end to another are the function of how the ancestral anima-mana (the sacred, the substratum of all being) is taken to reincarnate or manifest among the multivarious facets of the cosmos.

The primordial sacrificial religiosity is thus born out of the primitive understanding of energy-transformation and can be briefly summarized in this way : the primordial ancestor’s sacrifice has liberated the energy contained in him to create all the orders of the cosmos, plants and animals, each full of this ancestral energy, on which the social organism called human society feeds to thus subsist. These orders, say animals, are thus sacred, “totemic” to speak in the perspective of some, but in any case identified with the ancestor or god himself: e.g. bison, urus, whose signification “was found probably in its horns, which horns were then supposed to correspond to the horns of the moon, which moon itself was identified with the mother goddess. Hathor, the Egyptian goddess of moon, was a cow.” (René Bureau, "Esquisse d’une théorie sociologique du sacrifice", in Mort pour nos péchés, 3eme ed., publications des Facultés universitaires Saint-Louis, Bruxelles, p. 96.) The society gets hold of these sacred orders, destroys them, and liberates the energy therein to refuel itself and regenerate its order (communion sacrifice). Such liberation, however, exhausts the sacred order of the cosmos, and so part of the energy released from the destruction is deposited back (e.g. burnt back) to regenerate the cosmos’ own order (expiatory sacrifice) that is identified as the contemporary form of the primordial ancestor – and of all the ancestors whose soul has gone back to blend into it. Hence the testimony from Dogon as recorded by M. Griaule: “Ogotemmeli says to Griaule that by killing the victim, one liberates the vital force [i.e. energy] contained in its blood [blood as the concrete crystallization of its soul-life-force]; the Dogon word which corresponds to sacrifice means 'to make live': the ritual makes re-live at the same time the gods who have exhausted themselves while making the world continue [expiation], and men who have lost, by sickness or the violation of taboos, a part of their vital force [their energy, order, blood, soul: communion].” (“Remarques sur le mécanisme du sacrifice dogon” [1940], cited in ibid., p. 95: “Ogotemmêli dit à Griaule qu’en immolant la victime, on libère la force vitale contenue dans son sang; le mot dogon qui correspond à sacrifice signifie ‘faire vivre’: le rite fait reviver à la fois les divinités qui s’épuisent à faire durer le monde, et les hommes qui ont perdu, par la maladie ou la violation des tabous, une part de leur force vitale.") Then becomes intelligible, and in fact common-sense, all the symbolism of primitive, intraworld religiosity from diverse places of the world.15 Our next task is to analyze the details of this structure in terms of the primitive experience of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos.

POSTSCRIPT: (1) Émile Benveniste (in "Sacré", ibid.) has unearthed the same experience of the "sacred" (anima-mana) among the early Indo-Europeans through etymological studies. The four groups studied are the Indo-Iranians, the Germanic, the Latins, and the Greeks. In the Iranian case the word in question is spenta, which we have already encountered in Spenta Mainyu ("divine spirit"), and the seven deities of the elements are called the amesa spenta, the "immortal divines" (p. 181). Spenta is the Iranian designation of anima-mana, further associated with mathra ("parole efficace"), with xratu ("force mentale, vigueur de l'esprit"), with gatha, and originally derived from *k'wen, whence came sav-, "to be useful, advantageous, to profit". (p. 182 - 3) Thus "le verbe védique su- sva- signifie 'se gonfler, s'accroitre', impliquant 'force' et 'prospérité'; de là sura-, 'fort, vaillant'." (Ibid.) The ancestral anima-mana is energy which can energize and cause to grow; i.e. it is like food. But "to re-energize" can pass into "to reincarnate", as the energy coming into one to make oneself expand can be a sort of "re-materialization" of itself: "Le même rapport notionnel unit en grec le présent kuein 'être enceinte, porter dans son sein', le substantif kuma 'gonflement (des vagues), flot', d'une part, et de l'autre kuros 'force, souveraineté', kurios 'souverain'... Tant en indo-iranien qu'en grec, le sens évolue de 'gonflement' à 'force' ou 'prospérité'. Cette 'force' définie par l'adjectif av. sura est force de plénitude, de gonflement [the force of re-energization!]. Finalement, spenta caractérise la notion du l'être pourvu de cette vertu, qui est développement interne, croissance et puissance [and can thus serve as food, restaurant!]... Le caractère saint et sacré se définit ainsi en une notion de force exubérante et fécondante, capable d'amener à la vie, de faire surgir les productions de la nature." (p. 183 - 4) The sacred is the anima-mana which is "energy", and re-energizes.

That which re-energizes, i.e. stabilizes an ordered system away from equilibrium, is conducive to health. Hence in Germanic we find the related pair of "holy" (heilig) and "healthy" (Gothic adjective, hails; "hails traduit ugihV, ugiainwn 'en bonne santé, sain'; ga-hails traduit oloklhroV 'entier, intact', adjectif négatif un-hails, arrwstoV, kakwV ecwn 'malade'... Du thème nominal proviennent les verbes (ga)hailjan 'rendre sain, guérir'..." p. 186) which shows up in English as "holy" and "whole". "Le prototype de toutes ces formes se ramène à un adjectif *kailos, complètement ignoré de l'indo-iranien et du grec et qui, même dans les langues occidentales, est restreint à un groupe salve, germanique, celtique." (p. 187) The Germanic word related to the Avesta spenta is the Gothic weihs, which gets replaced by hails, hailig (p. 184, 187).

The sacred as the energetic and the re-energizing then passes into the taboo of its unscrupulous use. We have just seen the Latin example of this. On the Greek side the word for sacred is hieros, whose Vedic cognate is isirah, with the same energetic meaning of "vigour" and "liveliness". E.g. "l'épithète isirah s'ajoute au nom du vent: isiro vatah 'le vent rapide' ou 'agité'..." (p. 193) But when said of drinks (such as soma) it means "refreshing" or "makes vigourous", i.e. re-energizing. (Ibid.) The evolution of the meaning of hieros is posited as: from "strong" ("fort") through "permeated with force through divine influence" ("rempli de force par une influence divine") to "sacred". (p. 194) The Greek hosie, hosios on the other hand are the opposite of the Latin sanctus, i.e. the breaking of the taboo and the release of divine energy (anima-mana): "[Le hosie] ne signifie ni 'offrande' ni 'rite', mais bien le contraire: c'est l'acte qui rend le 'sacré' accessible, qui transforme une viande consacrée aux dieux en une nourriture que les hommes peuvent consommer... l'acte de désacralisation." (p. 200; in the culinary origin of taboo, then, hosie was women's cooking!) Thus the saying in the Hymn to Apollo, v. 237, wV osih egeneto, in relation to the custom of Onchestos and which Liddell-Scott translate as "the rites were established", actually means the repetition of the phrase "In the beginning was the hosie": in the beginning the primordial sacrifice of the god caused the release of energy in order for the world-order to be constituted (diakosmon), like the first flaming of the sun; subsequently the violation of the sacred has to be periodically repeated to re-generate the world-order against its entropic disintegration (hence the dictum of Cyrene: ton hiaron hosia panti, "the sacred (hiaron) is now accessible (hosia) to all"). What were established were not the rites, but the periodic releases of the anima-mana through the destruction of its embodiment-animals. While hieros corresponds to the Latin sacer, it is hagios which matches up with sanctus: "Enfin hieros et hagios montrent clairement l'aspect positif et l'aspect négatif de la notion: d'une part ce qui est animé d'une puissance et d'une agitation sacrées, d'autre part ce qui est défendu, ce avec quoi on ne doit pas avoir de contact." (p. 207) That Benveniste is here relying on Hubert-Mauss' scheme of sacralizing-desacralizing -- which we do not share -- does not concern us at the moment, and we'll consider in greater detail the Greek expression of the experience of the "sacred" later ("Greek Religion"). That different Indo-European languages use words derived from different roots to express the experience of the sacred mana vs. its taboo means not just that the Proto-Indo-Europeans did not have systematically fixed rituals expressed by fixed vocabulary, but rather more significantly that the experience of the sacred and its taboo was so basic to human experience as to repeat itself in all descendants groups of the Proto-Indo-Europeans who continually found different words for it.