|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One 1.3. Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions Chapter 6: Aztec (Mesoamerican) religion ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One 1.3. Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions Chapter 6: Aztec (Mesoamerican) religion ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

Copyright © 2005 by Lawrence C. Chin. You may print this out, but quotations, etc., require that proper references be given.

1. The cosmological mode: the cosmic politea manifested in the spatiality of the cosmos. The Aztec civilization is a chiefdom society, in evolution between the tribal stage and state-proper, the same as the Chinese Shang. It started when around 1325 a Chichimec group called Mexica settled Tenochtitlan; they built up the Aztec empire within a hundred years. In accordance with the microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism of the functional perspective, the Aztec built into their city a close correspondence between the cosmic structure and the political state. And this correspondence is already a full-blown cosmological mode, so that its symbolism mirrors closely that of the Chinese even of the imperial stage. We'll see here how the ideal structure of primitive (pre-salvational, "intraworld") religious experience we have isolated can again allow us to enter into the perspective of the Aztecs and comprehend their religious activities as something like common sense. Here we use David Carrasco, “Aztec Religion,” in Mircea Eliade, ed., Encyclopedia of Religion, vol. 2, p. 24 - 9.

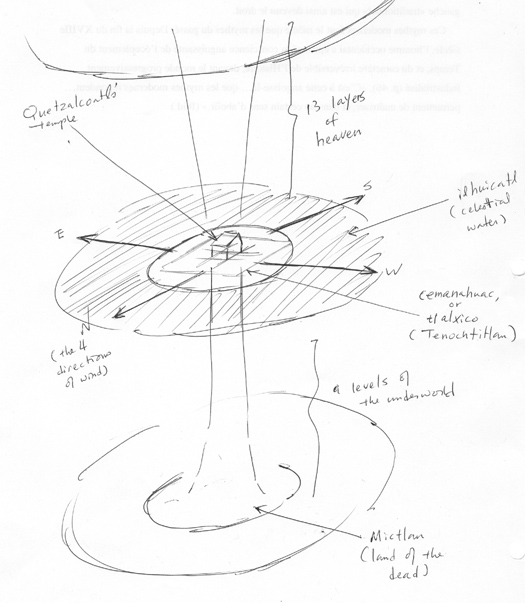

As elsewhere, the axis mundi and the omphalos -- based on the primitive understanding of the thermodynamics of order-formation as an island of low entropy in an equilibrium surrounding -- form the basic spatiality of the cosmos for the Aztecs (and Mesoamericans in general): "The image of the capital city as the foundation of heaven, which the Aztec conceived of as a vertical column of 13 layers extending above the earth" (Carrasco, p. 24) -- this is axis mundi. Already the great imperial city Teotihuacan, to which both the Toltec and the Aztec looked back as their symbolic place of origin, "was organized into 4 great quarters around a massive ceremonial center. Scholars and archaeologists have theorized that the four-quartered city was a massive spatial symbol for the major cosmological conceptions of Aztec religion." (Ibid.) The Aztecs built their capital city Tenochtitlan on the same spatial model. "The spatial paradigm of the Aztec cosmos was embodied in the term cemanahuac, meaning the 'land surrounded by water'." (p. 25) The land of human habitat itself is a omphalos. "At the center of this terrestrial space, called tlalxico ('navel of the earth' [i.e. the omphalos]), stood Tenochtitlan, from which extended the 4 quadrants called nauchampa, meaning 'the 4 directions of the wind.'" (Ibid.) We have here the spatial structure of the cosmological mode clearly expressed: the central order formation extending outwards in the four directions of East, West, North, and South, such as also so clearly expressed in the Chinese Yijing metaphysics. One can easily see how a little more differentiation of this spatial structure may result in the Chinese sacred 9-fold division of land (symbolized by the character for "well"):

|---------------------| |--------------------| | ^ | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |------|------|------| |< --- omphalos --->| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |------|------|------| | | | | | | | v | | | | | |---------------------| |--------------------| |

Just as the earth is the omphalos (order-formation) in the middle of the cosmic sea, and human habitation the omphalos in the midst of the earth, so ritual center is the omphalos in the midst of the human habitation from which the extremest order-formation, "consciousness of order", radiates, as seen in the legend about the earlier Toltec: "a number of accounts of the cosmic history culminate with the establishment of the magnificent kingdom of Tollan where Quetzalcoatl the god and Topiltzin Quetzacoatl the priest-king organize a ceremonial capital divided into 5 parts with 4 pyramids and 4 sacred mountains surrounding the central temple. This city, Tollan, serves as the heart of an empire. Aztec tradition states that 'from Quetzacoatl flowed all art and knowledge,' representing the paradigmatic importance of the Toltec kingdom and its religious founder." (p. 25)

"The waters surrounding the inhabited land were called ilhuicatl, the celestial water that extended upward to merge with the lowest levels of the 13 heavens. Below the earth were nine levels of the underworld, conceived of as 'hazard stations' for the souls of the dead, who, abided by magical charms buried with the bodies, were assisted in their quests for eternal peace at the lowest level, called Mictlan, the land of the dead." (p. 25 -6) Just as in the Chinese Yijing conception, the macrocosmo-microcosmic concentricism of the cosmological mode of the functional perspective dictates for the Aztecs that this spatial structure of the cosmos be repeated as the temporal structure of the cosmos as well: "The Mesoamerican pattern of quadrapartition around a center... was [also] used in the Aztec conceptions of temporal order as depicted in the famous Calendar Stone, where the four past ages of the universe are arranged in orderly fashion around the fifth or central age." This cosmic politea repeats itself in every other domain of the cosmic structure: "Recent research has shown that this same spatial model was used to organize the celestial order of numerous deity clusters, the architectural design of palatial structures, the collection of economic tribute in the empire, and the ordering of major ceremonial precincts." (p. 26)

2. The Aztec Anima system: the "sacred" of the Aztec

| One of the most striking characteristics of the surviving screenfolds... is the incredible array of deities who animated the ancient Mesoamerican world. Likewise, the remaining sculpture and the sixteenth-century prose accounts of Aztec Mexico present us with a pantheon so crowded that H.B. Nicholson's authoritative study of Aztec religion ["Religion in Pre-Hispanic Central Mexico" in Handbook of Middle American Indians, ed. Robert Wauchope,, vol. 10. 1971] includes a list of more than 60 distinct and interrelated names. Scholarly analysis of these many deities suggests that virtually all aspects of existence were considered inherently sacred and that these deities were expressions of a numinous quality that permeated the "real" world. Aztec references to numinous forces, expressed in the Nahuatl word teotl, were always translated by the Spanish as "god", "saint", or "demon". But the Aztec teotl signified a sacred power manifested in natural forms (a rainstorm, a tree, a mountain), in persons of high distinction (a king, an ancestor, a warrior), or in mysterious and chaotic places. What the Spanish translated as "god" really referred to a board spectrum of hierophanies that animated the world. [In other words, teotl, like the Nuer kwoth, Polynesian mana, or even the Chinese qi and the Egyptian maat, is just the Aztec word for the "sacred" and refers most appropriately to the atmosphere, air, the ancestral anima, which is then manifested in a variety of deities.] While it does not appear that the Aztec pantheon or pattern of hierophanies was organized as a whole, it is possible to identify clusters of deities organized around the major cult themes of cosmognoic creativity, fertility and regeneration, and war and sacrificial nourishment of the Sun. [Moreover, t]he general structuring principle for the pantheon, derived from the cosmic pattern of a center and four quarters, resulted in the quadruple or quintuple ordering of gods. For instance in the Codex Borgia's representation of the Tlaloques (rain gods), the rain god, Tlaloc, inhabits the central region of heaven while four other Tlaloques inhabit the four regions of the sky, each dispensing a different kind of rain. While deities were invisible to the human eye, the Aztec saw them in dreams, visions, and in the "deity impersonators" (teixiptla) who appeared at the major ceremonies... [They were] sometimes human, sometimes effigies of stone, wood, or dough... [In other words, the anima can take possession of people and things at special times, i.e. animate them.] (p. 26) |

The patron deities, as the ancestral animae proper to a group, followed and guided the migrating Chichimec who were the founder of the Aztec empire. In such circumstance the "patron deities... were represented in the tlaquimilolli, or sacred bundles" -- i.e., the idols or mana-poles wherein the anima-mana was especially concentrated and localized -- "that the teomamas ('godbearers', or shaman-priests) carried on their backs during the long journeys. The teomama passed on to the community the divine commandments communicated to him in visions and dreams" and thus became the authority figures in charge of the group's migration and settlement. (Ibid.) Note also that a "familiar pattern in the sacred histories of Mesoamerican tribal groups is the erection of a shrine to the patron deity as the first act of settlement in a new region... In reverse fashion, conquest of a community was achieved when the patron deity's shrine was burned and the tlaquimilolli was carried off as a captive." (Ibid.) Compare this with the Assyrian conquest of Israel and carry-off of the Covenant, and with the practice in China during the Warring Kingdoms where the conquest of a kingdom by another was signified by the victor's carry-off of the loser's sacrificial (bronze) vessels with which their royal house made offerings to its ancestors. "This pattern of migration, foundation, and conquest associated with the power of a patron deity is clearly exemplified by the case of Huitzilopochtli, patron of the wandering Mexica. According to the Aztec tradition, Huitzilopochtli inspired the Mexica teomama to guide the tribe into the Valley of Mexico, where he appeared to them as an eagle on a cactus in the lake. There they constructed a shrine to Huitzilopochtli and built their city around the shrine. This shrine became the Aztec Great Temple, the supreme political and symbolic center of the Aztec empire. It was destroyed in 1521 by the Spanish, who... carried the great image of Huitzilopochtli away..." (26 - 7)

3. The entropic cycles of the cosmos: cosmogony and the ages of the cosmos. The cosmos in the Aztec perspective displays the same entropic cycles of (restoration to) low entropic state and subsequent degeneration to high entropic state (collapse of order) that are seen among the cosmic conception of all ancient and primitive peoples of the functional perspective. However, "[e]ven though the cosmic order fluctuated between periods of stability and periods of chaos, the emphasis in many myths and historical accounts is on the destructive forces which repeatedly overcame the ages of the universe, divine society, and the cities of the past." (p. 25)

A. The creation of the cosmos: the first establishment of the low entropic state. The creation of the cosmos was credited to the highest god of the Aztec Anima system, Ometeotl ("lord of duality"), who was "androgynous.... the... omnipresent foundation of all things. In some sources he/she appears to merge with a number of his/her offspring... Ometeotl's male aspects (Ometecuhtli and Tonacatecuhtli) and female aspects (Omecihuatl and Tonacacihuatl) in turn merged with a series of lesser deities associated with generative and destructive male and female qualities. The male aspect was associated with fire and the solar and maize gods. The female aspect merged with earth fertility goddesses and especially corn goddesses." (p. 27) This highest god, in other words, was the generic anima (atmosphere) with moreover a duality within, and from which particular animae may be isolated. But this does not mean that s/he did not have a particular "home", a place of origination or "concentration": "Ometeotl inhabited the thirteenth and highest heaven in the cosmos, which was the place from which the souls of infants descended to be born on earth" (ibid.), i.e. all the animae within the general "atmosphere" that were concentrated in the place of their origination and which were to be re-incarnated in the material bodies on earth. The way in which Ometeotl created the cosmos was, according to the sixteenth-century prose account Historia de los Mexicanos por sus pinturas, by generating four offspring, "the Red Tezcatlipoca ('smoking mirror'), the Black Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl ('plumed serpent'), and Huitzilopochtli ('hummingbird on the left'). [Elsewhere the four offspring were: Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Xiuhtecuhtli, and Tlaloc; p. 27.] They all exist without movement for 600 years, whereupon the four children assemble 'to arrange what was to be done and establish the law to be followed.' Quetzalcoatl and Huitzilopochtli arrange the universe and create fire, half of the sun ('not fully lighted but little'), the human race, and the calendar. Then the four brothers create water and its divine beings." (p. 25)

The special character about the offspring Tezcatlipoca is that he "was the supreme active creative force of the pantheon... and was partially identified with the supreme numinosity of Ometeotl... [but] also identified with Itztli, the knife and calendar god, and with Tepeyolotl, the jaguar-earth god known as the Heart of the Hill, and he was often pictured as the divine antagonist of Quetzalcoatl. On the social level, Tezcatlipoca was the arch-sorcerer whose smoking obsidian mirror revealed the powers of ultimate transformation associated with darkness, night, jaguars, and shamanic magic." (p. 27) Remember that the animistic perspective sees all dynamic aspects of reality as the result of animation, i.e. of being animated by the particular "force" proper to each as if by air. Cutting with a knife, for instance, is an action carried by the animating principle (in analogy with air) of cutting-with-knife, which is then the "god of knife", and so on. Sexual passion then also must be directed by an animating principle which is thus the god of sexual powers and passions, Tlazolteotl (below). Centeotl, goddess of maize; Xilonen, goddess of the young maize; and Ometochtli, goddess of maguay then are all animae which animate the growth dynamics of maize and maguay.

B. The four eras. The cosmogony then continues thusly:

|

Following this rapid and full arrangement, the sources focus on a series of mythic events... The universe passes through four eras, called "Suns". Each age was presided over by one of the great gods, and each was named for the day (day number and day name) within the calendrical cycle on which the age began (which is also the name of the force that destroys the sun). The first 4 Suns were called, respectively, 4 Jaguar, 4 wind, 4 Rain (or 4 Rain of Fire), and 4 Water. The name of the fifth (and last) cosmic age, 4 Movement, augured the earthquakes that would inevitably destroy the world.

The creation of this final age, the one in which the Aztec lived, took place around a divine fire in the darkness on the mythical plain of Teotihuacan (to be distinguished from the actual city of that same name). According to the version of this story reported in Fray Bernadino de Sahagun's Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva Espana.... an assembly of gods chose two of their group, Nanahuatzin and Tecuciztecatl, to cast themselves into the fire in order to create the new cosmic age. Following their self-sacrifice, dawn appears in all directions, but the Sun does not rise above the horizon. In confusion, different deities face in various directions in expectation of the sunrise. Quetzalcoatl faces east and from there the Sun blazes forth but sways from side to side without climbing in the sky. In this cosmic crisis, it is decided that all the gods must die at the sacrificial hand of Ecatl, who dispatches them by cutting their throats. Even this massive sacrifice does not move the Sun until the wind god literally blows it into motion. These combined cosmogonic episodes demonstrate the fundamental Aztec conviction that the world is unstable and that it draws its energy from massive sacrifices by the gods. (p. 25, emphasis added.) |

Whereas all cultures understand the thermodynamics that the differentiated order of the cosmos (diakosmos) cannot be established and kept running without the input of energy released from the destruction of gods who are concentrated with energy (just as car isn't running unless fossil fuel is burnt in its tank to release energy to power it), the Aztec apparently have a more exaggerated sense of the energy needed to overcome the natural (downhill) state of high entropy: like a half broken machine, the cosmos could only be "started off" rather clumsily with the infusion of energy contained in a few gods, and only completely be "powered up" to be running at full capacity when a whole hoard of gods are sacrificed.

4. The Aztec human sacrifice to feed the gods and the structuration of temporality. That the purpose of sacrifice is to feed energy into the Anima (atmosphere) running the cosmos in order to maintain the differentiated order or low entropy of the cosmos -- and not about violence (e.g. finding scapegoats) -- is most clearly demonstrated by the famed Aztec religious practice of human sacrifice, "usually carried out for the purpose of nourishing or renewing the Sun or other deity (or to otherwise appease it), thus ensuring the stability of the universe." (p. 28, emphasis added.) Following the first massive sacrifice of the gods to power the Sun in the beginning of the fifth age, "Tonatiuh, the personification [or anima, soul] of that Sun (whose visage appears in the center of the Calendar Stone), depended on continued nourishment from human hearts." (Ibid.)

"Some of the large-scale sacrificial ceremonies re-created other sacred stories. For example, women and masses of captive warriors were sacrificed in front of the shrine of Huitzilopochtli atop the Templo Mayor. Their bodies tumbled down the steps to rest at the bottom with the colossal stone figure of Coyolxauhqui, Huitzilopochtli's dismembered sister, symbolically reenacting the legendary slaughter of the four hundred siblings at Huitzilopochtli's birth." (Ibid.)

"War was therefore waged to obtain the holy food that the Sun required, and thus to perpetuate life on Earth. The Aztecs used no terms like 'human sacrifice' for their rituals. For them it was nextlaualli, the sacred debt payment to the gods." Recall the primordial guilt or debt. "Thus warfare, sacrifice, and the promotion of agricultural fertility were inextricably linked in their religious ideology." (John M. D. Pohl, "Aztecs: A New Perspective" in History Today, Dec. 2002, p. 11.) War for the Aztecs is thus no different than hunting animals and gathering plants to keep oneself fed, except that here they are gathering food for the gods!

"Cosmology, pantheon, and ritual sacrifice were united and came alive in the exuberant and well-ordered ceremonies carried out in the more than 80 buildings situated in the sacred precinct of the capital and in the hundreds of ceremonial centers throughout the Aztec world. Guided by detailed ritual calendars, Aztec ceremonies varied from town to town but typically involved three stages: days of ritual preparation, death sacrifice, and nourishing the gods." As pointed out, the human experience of time was in primitive time determined by the repeated intervals (cycles) of re-fuelling (restoration to low entropy), use and exhaustion of energy (decline to maximal entropy), and refuelling again. Just as the day is ordered by the refuelling of the body during breakfast, lunch, and dinner, so the year is ordered by the refuelling of the god-cosmos: hence the relationship between calendar and sacrifice (meal time for gods).

|

The days of ritual preparation included fasting; offerings of food, flowers, and paper; use of incense and purification techniques; embowering; songs; and processions of deity-impersonators to various temples in ceremonial precincts.

Following these elaborate preparations, blood sacrifices were carried out by priestly orders specially trained to dispatch the victim swiftly. [One must not assume intentional cruelty behind this dispatch; the mind of the priests and the sacrificers was as always focused on the preparation of nourishment for the gods; that sufferings had to accompany the release of energy to regenerate the gods was either ignored or taken as a necessary evil.] The victims were usually captive warriors or purchased slaves. Though a variety of methods of ritual killing were used, including decapitation, burning, hurling from great heights, strangulation, and arrow sacrifice, the typical ritual involved the dramatic heart sacrifice and the placing of the heart in a ceremonial vessel (cuauhxicalli) in order to nourish the gods. Amid the music of drums, conch shell trumpets, rattles, and other musical instruments, which created an atmosphere of dramatic intensity, blood was smeared on the face of the deity's image and the head of the victim was placed on the giant skull rack (tzompantli) that held thousands of such trophies. All of these ceremonies were carried out in relation to two ritual calendars, the 365-day calendar or tonalpohualli ("count of day") consisting of 18 20-day months plus a 5-day intercalay period and the 260-day calendar consisting of 13 20-day months. More than one third of these ceremonies were dedicated to Tlaloc and earth fertility goddesses. Besides ceremonies relating to the two calendars, a third type of ceremony related to the many life cycle stages of the individual. In some cases, the entire community was involved in bloodletting. (Carrasco, ibid.) |

The fertility-rain god Tlaloc "dwelt on the prominent mountain peaks, where rain clouds were thought to emerge from caves to fertilize the land through rain, rivers, pools, and storms. The Aztec held Mount Tlaloc to be the original source of the waters and vegetation." (p. 27) Offerings, i.e. energy then needed to be in-put to this god so as to be transformed into water coming out from the other end to fertilize the land (do ut des). "Two other major gods intimately associated with Tlaloc were Chalchihuitlicue, the goddess of water, and Ehecatl, the wind god, an aspect of Quetzalcoatl." (Ibid.) Offerings can be expected in this respect to facilitate the emergence of Ehecatl whose "forceful presence announced the coming of the fertilizing rains." (Ibid.)

| The most powerful group of female fertility deities were the teteoinnan, a rich array of earth-mother goddesses, who were representatives of the... qualities of terror and beauty, regeneration and destruction. These deities were worshiped in cults concerned with [i.e. attempts were made to influence them to facilitate] the abundant powers of the earth, women, and fertility. Among the most prominent were Tlazolteotl, Xochiquetzal, and Coatlicue. Tlazolteotl was concerned with sexual powers and passions and the pardoning of sexual transgressions. Xochiquetzal was the goddess of love and sexual desire.... A ferocious goddess, Coatlicue ("serpent skirt") represented the cosmic mountain that conceived all stellar beings and devoured all beings into her repulsive, lethal, and fascinating form. Her statue is studded with sacrificed hearts, skulls, hands, ferocious claws, and giant snake heads. (Ibid., emphasis added.) |

There is also another regenerative, fire ritual associated with Xiuhtecuhtli, one of the first four offspring of Ometeotl:

| Xiuhtecuhtli was represented by the perpetual "fire of existence" that were kept lighted at certain temples in the ceremonial center at all times. He was manifested in the drilling of new fires that dedicated new ceremonial buildings and ritual stones. Most importantly, Xiuhtecuhtli was the generative force at the New Fire ceremony, also called the Binding of the Years, held every 52-years on the Hill of the Star outside of Tenochtitlan. At midnight on the day that a 52 year calendar cycle was exhausted, at the moment when the star cluster we call the Pleiades passed through the zenith, a heart sacrifice of a war captive took place. A new fire was started in the cavity of the victim's chest, symbolizing the rebirth of Xiuhtecuhtli. The new fire was carried to every city, town, and home in the empire, signalling the regeneration of the universe. On the domestic level, Xiuhtecuhtli inhabited the hearth, structuring the daily rituals associated with food, nurturance, and thanksgiving. (Ibid.) |

Xiuhtecuhtli therefore embodied, or served as the animating principle of, the universe in this respect and he was after a regular interval of time "running out", reaching maximal entropy. The human heart was then used as the fuel to refuel him, or namely the universe, to restore him/it to the former state of low entropy.

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |