copyright © 2003 by Lawrence. C. Chin. All rights

reserved.

Zeno did not intend his paradoxes to intimate quantum mechanics and relativity, but merely to show that, on logical ground, motion -- in the everyday common-sense understanding of it, that is -- had to be only an illusion. This is to defend Parmenides' vision of Being against the sophistic criticism of it based on positivistic, fundamentalist misunderstanding (immanentization of the transcendent Being rendered moreover present-at-hand [vorhanden]). The apparent irony is that Zeno's defense seems itself based on the same fundamentalist misunderstanding, which becomes a trend in the aftermath of Parmenides. The solutions offered to his paradoxes, whether by Aristotle or many of the modern time, are furthermore based on concentration on his words and the inability, unawares, to understand what he meant by these words. (The moderns may be excused since Aristotle did not preserve Zeno's words well.) The history of deformation since Parmenides is important for three reasons. (1) It shows that when the functional perspective reaches its height -- the total logical formulation of the perspective -- and has moved from its immature stage of the inability to conceive of anything except as "things" (mythic consciousness) to the mature stage of the ability to "see" (only with nous) the source of existence beyond the empirical world of things, the transition to the immature stage of the structural perspective sets in which is characterized by an increase in the breadth of knowledge about the empirical world of things (the enlargement of the experiential horizon) accompanied by the stripping of this world down to its present-at-hand aspect (Vorhandenheit) only, but also by the shrinking of the depth of consciousness through again the inability to conceive beyond "things" and their presence-at-hand. The fundamentalist destruction of the depth of consciousness previously achieved then begins. A preliminary overview of the history of human consciousness can be given. (2) The fundamentalist misunderstanding, the immanentization of the transcendent reality interestingly can have the effect of a deepened understanding of the structure of the empirical reality, as with Zeno and Democritus. (3) The recovery of spiritual depth within the debris of the sophists' fundamentalist destruction of philosophy -- the work of Plato -- results in the synthesis of the breadth of knowledge with the depth of consciousness, the empirical with the transcendental. This is similar to the present project of scientific enlightenment.

(1) Eric Voegelin gives an excellent exposition of the rise and function of sophism in Order and History, vol. II, The World of the Polis (Chapt. 11, p. 267). After the Persian Wars Athens rose to political and economic predominance among the Hellenes, and strove for cultural "catch-up". "In order to become, in the proud words of Pericles, the school of Hellas, Athens had to be its schoolboy for two generations. The education of Athens through Hellas to the point where the pupil became the undoubted representative of Hellenic culture was the decisive event of the so-called Age of the Sophists." (Ibid.) Sophists refer to the non-Athenian Hellenic polymaths who, as migrants looking for livelihood, came to Athens to educate the Athenians. "In the first place... the term applies to the men who by historiographic tradition are called sophists, and especially to the Great Four: Protagoras of Abdera, Gorgias of Leontini, Hippias of Elis, and Prodicus of Ceos... Beyond this center we must include among the relevant personnel the older generation of Zeno of Elea and Anaxagoras of Clazomenae [coming to Athens]... [These two] were the mediating link between the philosophy of Parmenides and the methods of argumentation developed by Protagoras and Gorgias. And there must also be included the personnel which mediated Pythagorean wisdom... as well as the men who mediated knowledge from the medical school of Cos." (Ibid. p. 268 - 9) Such others can also hesitatingly be fit into the sophistic atmosphere as Herodotus whose History, "with its information on customs of foreign civilizations, was a splendid support of sophistic relativism with regard to ethics," or even Thucydides. (Ibid., p. 269) The achievement of the sophists, with the shallowness of understanding (nous), was, as said, breadth, polymathic or polyhistoric, and the classification of knowledge which "was retained through the ages as the Quadrivium and the Trivium": "The Quadrivium of arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy" and "the Trivium of grammar, rhetoric, and dialectic". (Ibid., p. 271)

The sophist decline from the transcendental back to the world of things, and the revelation of the present-at-hand aspect of these things, just like the Enlightenment thinkers of the 18th century Europe, is accompanied by arrogance, which always comes with the shrinking of consciousness and the rising of stupidity... to which Plato's philosophy is reaction. "Plato opposed his 'God is the Measure' deliberately as the counter formula to Protagoras' 'Man is the Measure.' In sophistic thought... there was missing the link between the well-observed and classified phenomena of ethics and politics [and the empirical world of things] and the 'invisible measure' [the source of being beyond] that radiates order into the soul [the order of the mind from enlightenment: minor salvation]. The opposition to a world of thought without spiritual order [without the enlightened state of mind] was repeatedly expressed by Plato at critical junctures of his work." The sophist shrinkage back to things is also always accompanied by such positivism as the "set of agnostic, if not atheistic, propositions... (1) It seems that no gods exist; (2) Even if they do exist, they do not care about men; (3) Even if they care, they can be propitiated by gifts. Plato opposes to them his counter-propositions that the gods do exist, that they care about men, and that they cannot be appeased by prayer and sacrifice." (Ibid., p. 274; c.f. Book II of the Republic.) This reminds of the rise of atheism and agnostics in the 19th century Europe after much positivistic science; as said, the restriction of consciousness to thinghood is the condition of possibility for agnosticism.

Since the highest point of spirituality (mysticism, philosophy, anamnesis of the source) has been reached in Hellas with Parmenides' vision, the sophistic retreat from it means the destruction of it through positivistic fundamentalism, e.g. Gorgias' essay On Being [or Nature] or sometimes On Non-Being (Peri tou mh ontoV h Peri tou fusewV).1 "The Gorgian tract was concerned with Parmenidean problems. It was organized into three parts defending successively the following propositions:

- 1. Nothing exists [en men kai prwton oti ouden estin];

- 2. If anything exists, it is incomprehensible [deuteron oti ei kai estin, akatalhpton anqrwpwi];

- 3. If it is comprehensible, it is incommunicable [triton oti ei kai katalhpton, alla toi ge anexoiston kai anermhneuton twi pelaV...].2

In the first part of his tract Gorgias proved the nonexistence of Being. He proceeded by demonstrating the contradictions to which the Parmenidean predicates of Being will lead. We select as representative the argument on the predicate 'everlasting':

|

Being cannot be everlasting because in that case it would have no beginning [text of (69) has: All that which comes to be has some beginning, and the eternal is not-coming-to-be so as to not have a beginning.]; what has no beginning is boundless [apeiron]; and what is boundless is nowhere. For if it were anywhere it would have to be surrounded by something that is greater than itself [that in which it is. And that which is surrounded by some other will not be the apeiron. For the surrounding is greater than the surrounded]; but there is nothing that is greater than the boundless; hence the boundless is nowhere; and what is nowhere does not exist.

[(69) to gar ginomenon pan ecei tin'archn, to de aidion agenhton kaqertwV ouk ecein archn. mh econ de archn apeiron estin. ei de apeiron estin, oudamou estin. ei gar pou estin, eteron autou estin ekeino to en wi estin, kai outwV ouket'apeiron estai to on emperiecomenon tini. meizon gar esti tou emperiecomenou to emperiecon, tou de apeirou ouden esti meizon, wste ouk esti pou to apeiron.]

|

The abstract of the essay On Being is a priceless document because it has preserved one of the earliest... instance of the perennial type of enlightened philosophizing [i.e. positivistic, just the opposite of real enlightenment, the destruction of enlightenment]. The thinker operates on symbols that have been developed by mystic philosophers for the expression of experiences of transcendence. He proceeds by ignoring the experiential basis, separates the symbols from this basis as if they had meaning independent of the experience which they express, and with brilliant logic shows, what every philosopher knows, that they will lead to contradictions if they are misunderstood as propositions about [present-at-hand] objects in world immanent experience. [Only things of the empirical world can be surrounded.] Gorgias applied his acumen to the Parmenidean Being; but the same type of argument could be applied to other symbols of transcendence, and the set of three propositions about the gods are probably the summary of such an argument..." (Ibid., p. 275)

Gorgias does much word-play with being (to on) and non-being (to me on), and this empty word-playing without any experiential ground is another positivistic sophistry. The opposition of the non-Being of some Eastern enlightened ones and the Being of Western enlightened ones is not to be confused with such word-playing, for their words are grounded in experience of transcendence (the enlightened state of mind comporting toward the source of being).

At the time Parmenides' mystical, salvational experience of the source of being must have suffered such dismissals and rebuttals as fundamentalist misunderstanding of the Gorgian kind from all quarters, Pythagoreans, sophists, or otherwise.3 Zeno's defense of Parmenides against these unjustified derisions then consists also in transferring the characteristics of transcendent Being (Oneness, Immutability, etc.) onto the immanent world with thus the demonstration of the logical impossibility of plurality and motional change. The immanent world here is the world of common sense with immutable things moving in immutable space and time, i.e. that which underlies the immature stage of the functional perspective as well as of the structural (as in classical mechanics), and which happens to be illogical because the immature consciousness is illogical. It does not matter whether Zeno had with a positivistic mind really misunderstood Parmenides or was simply fighting dung with also dung -- not being serious with his paradoxes4 -- it is thus that he happened to have exposed the illogicality of the common sense notion of space, time, and motion which is at first transcended by the mystic philosophers at the end of the functional perspective and, when their insights faded out during the rise of the structural perspective, again corrected by quantum mechanics and relativity which are the expressions of the mature stages of the now structural perspective.

The modern sophistic spirits do not differ from the fault of their predecessors. As said, they throw much derisions upon the Greek mystics by turning their symbolism into analytical propositions about immanent objects or word-plays that seem ridiculous: the less intelligent making fun of the very wise as if the latter were idiots, unaware that they fail to comprehend something profound. This is a sign of the arrogance said to accompany positivism and stupidity in general.

"We may say that the [sophistic] age indeed has a streak of enlightenment insofar as its representative thinkers show the same kind of insensitiveness toward experiences of transcendence that was characteristic of the Enlightenment of the 18th century A.D., and insofar as this insensitiveness has the same result of destroying philosophy -- for philosophy by definition has its center in the experience of transcendence [i.e. is mystic]. Moreover, the essentially unphilosophical character of sophistic writings may have been the most important cause of their almost complete disappearance in spite of the impressive collection and organization of materials which they must have contained. For the materials could be taken over by later writers and, stripped of the materials, the writings held no interest for philosophers. And, finally, we can understand more clearly why Plato concentrated the essence of his own philosophizing in an emphatic counter-formula to the Protagorean homo - mensura. After the destruction of philosophy through the sophists, its reconstruction had to stress the Deus - mensura of the philosophers; and the new philosophy had to be clearly a type of theology." (Ibid.)

The lesson here is that consciousness in the Hellenic world started differentiating around 500 B.C.; that the result of the differentiation of consciousness was always, or rather could be, two-fold: one issuing into the tradition of spiritual enlightenment from the Milesian through the Italic Presocratics to the Athenian Socrates and Plato, i.e. the tradition of the maturity of the functional perspective; another into the reduction of the world to its bare present-at-hand empirical physicality. It is in this latter tradition -- the budding of an immature structural perspective -- that not only sophism but also the Hellenistic sciences later on belonged. This budding tradition however failed to come to fruition (the underlying reality of molecules and atoms below and the solar system above was never revealed) and was interrupted by the collapse of the classical world. The rise of classical mechanics and Enlightenment after Renaissance was the second time consciousness differentiated out the Vorhandenheit of reality -- in large measure based on the Hellenic, first time -- and this time it would fully blossom.

While positivism -- the denial of any reality beyond the empirical and measurable, and the conception of the empirical solely in its presence-at-hand, best exemplified by empiricism's demand of visibility and falsifiability, the arrogant attitude of "If I can't see or understand it, then it can't exist" -- is the expression of the immature stage of the budding structural perspective, its mature stage is the recovery of the experience, formerly achieved but now lost, of the transcendent, eternal reality that is the source of the empirical and falsifiable, with the correlative "depth of soul open to the divine", i.e. the enlightened, awakened state of mind. That is, mysticism, which is theology generalized or purged of images. Plato's reaction to the sophistic destruction of philosophy is paralleled today by, e.g. Heidegger's revival of metaphysics (remembrance of Being forgotten) against the deformation of Western philosophy into discourse on logical categories from the scholastic until German idealism on the European continent; and, in the English speaking world, when the reaction does happen here and there, by, e.g. Eric Voegelin's recovery of ancient experiences of transcendence against the Enlightenment tradition which evolves into the destruction of philosophy in "analytic philosophy" and derisions of it by scientists due to positivistic misunderstanding of the Gorgian type. These reactionaries are not considered here to be the final answer in modern time, as they are only recovery of the lost. Spirituality and its completion, mysticism, must be sought within the structural perspective and its new found knowledge themselves, i.e. the breadth of knowledge and enlarged experiential horizon will be retained together with the recovery of that which is now outside, this by correlating the lost experience of transcendence with the emerging experience of transcendence within such frontiers of science as modern physics: scientific enlightenment.

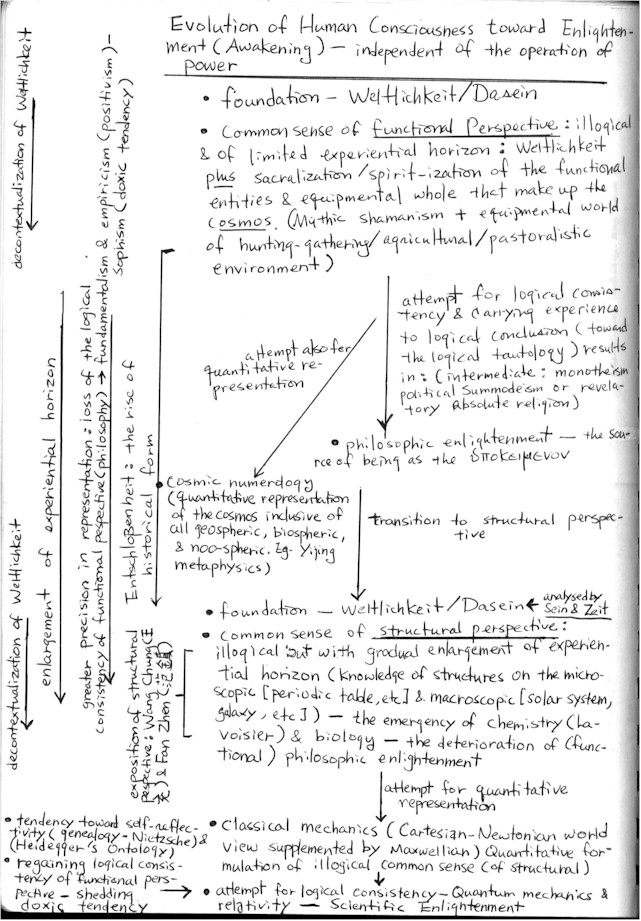

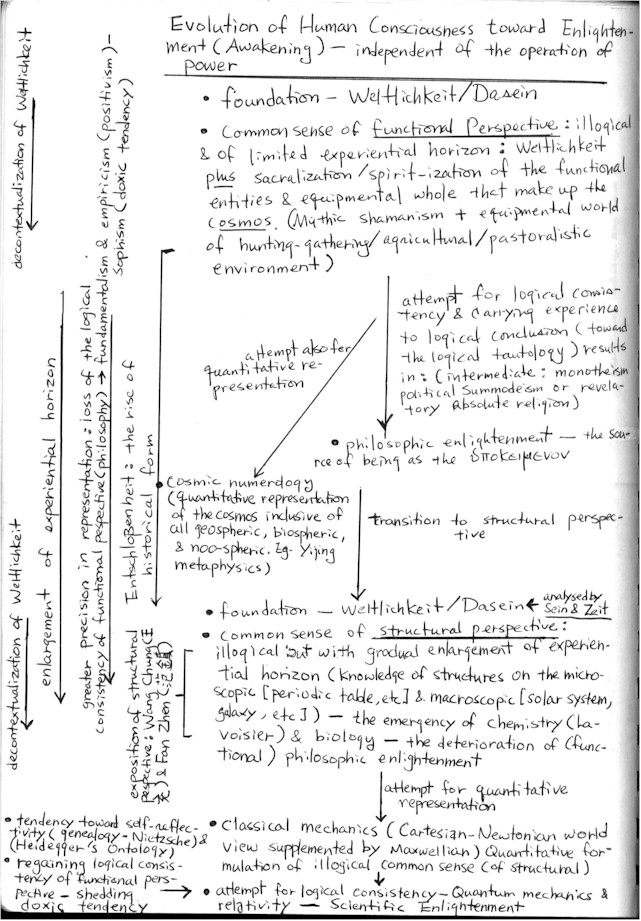

A simplified version of a preliminary view of the structure of the evolution of human consciousness since its inception until contemporary time can thus be given:

-- -------------------------------------

| New Physics - philosophy

| 2

| Heidegger's ontology of Dasein and

| Weltlichkeit as recapturing the found-

| ation and as reflexive metaphysics

| --------------------------------------

| chemistry and biology as

| the structural paradigm

STRUCTURAL--| &

| 1.3 complete, i.e. quantitative, exact

| formulation of common sense decontext-

| ualized worldliness (classical me-

| chanics)

|

|

| 1.2 decontextualized Weltlichkeit

|

| 1.1 semi-functional, semi-structural perspective

| & the non- (or less-) sacred Weltlichkeit

-- ---------------------------------------

STARTING OVER

-- ---------------------------------------

| 2 philosophy (non-reflexive)

|

| decontextualized Weltlichkeit

FUNCTIONAL--|

| 1 mythic, shamanistic world view

| & the sacred Weltlichkeit

-- ----------------------------------------

|

The more detailed view:

It is important to understand the evolution of consciousness in both its upward and downward dimension. At every stage of the advance in the differentiation of consciousness, there is a cross-road phenomenon, a possible divergence, one toward spiritual depravation (downward) and the other toward spiritual advancement (upward). Hence within the functional perspective, as the mythic consciousness disintegrates due to the differentiation of consciousness (decontextualization of Weltlichkeit), there appear the sophists, with symptoms of spiritual depravation manifested in their cultural relativism, nihilism, atheism, positivism (leading to fundamentalism or literalization of the symbols expressing spiritual enlightenment, seen above): this is the downward dimension. But at the same time there appears Plato, reasserting the traditional values of theism and absolutism (e.g. that justice is desirable in itself, the central theme in Republic) but this time on a more differentiated basis or on a higher level: this is the upward dimension toward spiritual enlightenment. During the Western Enlightenment of 1700s the differentiation of consciousness has resulted in a corpuscular, atomic, materialist conception of reality (what we will see later as the "de-animization of the cosmos") but this is expressed solely in the downward dimension, leading to spiritual depravation manifested in the Western I-it relationship toward nature, positivism (again!), atheism, nationalism, then communism, fascism, feminism... For this reason "science" is detested or ignored by many in the study of humanities wishing to avoid the downward fall. It is the upward dimension of the structural perspective that is attempted here: hence scientific enlightenment.

Footnotes:

1. Sext. in Hermann Diels, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Gorgias, B 3. Diels notes: "Die Identitaet der Schriften Peri tou mh ontoV und Peri fusewV ist strittig [controversial]."

2. I'm not sure of the meaning of the Greek here.

3. In his Parmenides, Plato wrote: ... esti de to ge alhqeV bohqeia tiV tauta [ta grammata] twi Parmenidou logwi proV touV epiceirountaV auton kwmwidein wV, ei en esti, polla kai geloia sumbainei pascein twi logwi kai enantia autwi. "In truth is the book some sort of defense for Parmenides against those attempting to make fun of him by showing that, if all is One, many absurd (laughable) and contradictory consequences would follow from his logos." (Cited by Kirk and Raven, p. 186) Here it is said that the deriders were Pythagoreans. Nick Huggett (ibid.) sums up: "For the first half of the Twentieth century the majority reading -- following Tannery -- of Zeno held that his arguments were directed against a technical doctrine of the Pythagoreans. According to this reading they held that all things were composed of elements that had the properties of a unit number, a geometric point and a physical atom: this kind of position would fit with their doctrine that reality is fundamentally mathematical. However, in the middle of the century a series of commentators (Vlastos, 1967...) forcefully argued that Zeno's target was instead a common sense understanding of plurality and motion -- one grounded in familiar geometrical notions -- and indeed that the doctrine was not a major part of Pythagorean thought. We have implicitly assumed that these arguments are correct in our readings of the paradoxes. That said, Tannery's interpretation still has its defenders." It is more important here to understand the nature of derisions, of which any un-enlightened positivistic soul is incapable.

4. This possibility is suggested by Plato's words following the previous: antilegei dh oun touto to gramma proV touV ta polla legontaV, kai antapodidwsi tauta kai pleiw, touto boulomenon dhloun, wV eti geloiotera pascoi an autwn h upoqesiV, ei polla estin, h h tou en einai, ei tiV ikanwV epexioi. "This book retorts against those saying [reality] to be plural, and it pays them back in their own coin, and more [to spare], by showing that yet more absurd (laughable) consequences would follow from the hypothesis that reality is plural than from that reality is One -- if one examines the matter more sufficiently." (Kirk and Raven, Ibid.)