Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial

2.B.1. A Genealogy of Philosophic Enlightenment in Classical Greece

Chapter 16: Plato's Divided Line

ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY

|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial 2.B.1. A Genealogy of Philosophic Enlightenment in Classical Greece Chapter 16: Plato's Divided Line ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

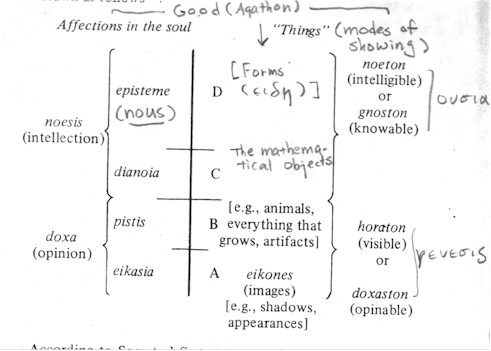

1. The description of the divided line. After stating that there are these two kinds of showing, the intelligible and the visible (duo autw einai, 509 d), Socrates lays out the prescription for the divided line:

| Wsper toinun grammhn dica tetmhmenhn labwn anisa tmhmata, palin temne ekateron to tmhma ana ton auton logon, to te tou orwmenou genouV kai to tou nooumenou, kai soi estai safhneiai kai asafeiai proV allhla en men twi orwmenwi to men eteron tmhma eikoneV -- legw de taV eikonaV prwton men taV skiaV, epeita ta en toiV udasi fantasmata kai en toiV osa pukna te kai leia kai fana sunesthken, kai pan to toiouton, ei katanoeiV. (509 e) |

Then take a line cut in two unequal segments, one for the kind that is seen, the other for the kind that is intellected -- and go on and cut each segment in the same ratio. Now, in terms of the clarity and obscurity with one another, you'll have one segment in the visible part for images. I mean by images first shadows, then appearances produced in water and in all close-grained, smooth, bright things, and everything of the sort, if you understand. [Segment A]

|

As John Sallis notes, "Th[e] first statement tells us three very important things about the line. First, it tells us that the major division of the line corresponds to the distinction between intelligible and visible. Second, it indicates the basic proportionality of the division. And third, it indicates that the principle of the proportionality is degree of clarity (safhneia), that is, that the relative lengths of the segment corresponds to the degree of clarity exemplified by what the various segments signify." (Being and Logos, p. 413) Then Socrates specifies that the least clear of all in the matter of self-showing, shadows and reflections, etc., are to be put at the bottommost of the four segments (A).

|

To toinun eteron teqei wi touto eoiken, ta te peri hmaV zwia kai pan to futeuton kai to skeuaston olon genoV. ...... H kai eqeloiV an auto fanai... dihirhsqai alhqeiai te kai mh, wV to doxaston proV to gnwston, outw to omoiwqen proV to wi wmoiwqh; (510 a 5 - 10) |

Then in the other segment put that of which this first is the likeness -- the animals around us, and everything that grows, and the whole genus [kind] of artifacts. [B]

...... And would you also be willing... to say that with respect to truth or lack of it, as the opinable is distinguished from the knowable, so the likeness is distinguished from that of which it is the likeness? |

This means that the lower division of the visible world A and B is an image of the upper division of the intelligible world C and D, and that the lower segment of each of the division is likewise an image of the upper segment of the same division (A is an image of B and C of D) -- all this just as the opinable is an image of the knowable. Then Socrates describes how the upper division of the intelligible should be cut:

| Hi to men autou toiV tote mimhqeisin wV eikosin crwmenh yuch zhtein anagkazetai ex upoqesewn, ouk ep'archn poreuomenh all'epi teleuthn, to d'au eteron -- to ep'archn anupoqeton -- ex upoqesewV iousa kai aneu twn peri ekeino eikonwn, autoiV eidesi di'autwn thn meqodon poioumenh. (510 b4) | In one part of it a soul, using as images the things that were previously imitated, is compelled to investigate on the basis of hypotheses [lit. from "presuppositions"] and makes its way not to a beginning [arche] but to an end [teleuten; this is segment C, that for the mathematical objects]; while in the other part [i.e. segment D, that for forms] it makes its way to a beginning that is free from hypothesis [lit. unpresupposed], starting out from hypothesis and without the images used in the other part, by means of forms themselves it makes its enquiry through them. |

Asked about what this means, Socrates explains further. First, about segment C, the proper domain of "geometry and its kindred arts" (gewmetriaiV te kai taiV tauthV adelfaiV tecnaiV; 511 b):

|

oimai gar se eidenai oti oi peri taV gewmetriaV te kai logismouV kai ta toiauta pragmateuomenoi, upoqemenoi to te peritton kai to artion kai ta schmata kai gwniwn tritta eidh kai alla toutwn adelfa kaq'ekasthn meqodon, tauta men wV eidoteV, poihsamenoi upoqeseiV auta, oudena logon oute autoiV oute alloiV eti axiousi peri autwn didonai wV panti fanerwn, ek toutwn d'arcomenoi ta loipa hdh diexionteV teleutwsin omologoumenwV epi touto ou an epi skeyin ormhswsi.

....... Oukoun kai oti toiV orwmenoiV eidesi proscrwntai kai touV logouV peri autwn poiountai, ou peri toutwn dianooumenoi, all 'ekeinwn peri oiV tauta eoike, tou tetragwnou autou eneka touV logouV poioumenoi kai diametrou authV, all'ou tauthV hn grafousin, kai talla outwV, auta men tauta a plattousin te kai grafousin, wn kai skiai kai en udasin eikoneV eisin, toutoiV men wV eikosin au crwmenoi, zhtounteV de auta ekeina idein a ouk an allwV idoi tiV h thi dianoiai......... Touto toinun nohton men to eidoV elegon, upoqesesi d 'anagkazomenhn yuchn crhsqai peri thn zhthsin autou, ouk ep'archn iousan, wV ou dunamenhn twn upoqesewn anwterw ekbainein, eikosi de crwmenhn autoiV toiV upo twn katw apeikasqeisin kai ekeinoiV proV ekeina wV enargesi dedoxasmenoiV te kai tetimhmenoiV. (510 c - 511 a) |

I suppose you know that the men who work in geometry, calculation, and the like treat [i.e. presuppose: hypothesize] as known the odd and the even, the figures, three forms of angles, and other things akin to these in each kind of enquiry. These things they make hypotheses and don't think it worthwhile to give any further account of them to themselves or to others, as though they are clear to all. Beginning from them, they go ahead with their exposition of what remains and end consistently [lit. all having agreed] at the object toward which their investigation was directed.

....... Don't you also know that they use visible forms besides and make their arguments [logoi] about them, not thinking about them but about those others that they are like? They make arguments for the sake of the square itself and the diagonal itself, not for the sake of the diagonal they draw, and likewise with the rest. These things themselves that they mold and draw of which there are shadows and images in water, they now use as images, seeking to see those things themselves, that one can see in no other way than with thought. ........ This is the form I said was intelligible (noeton). However, a soul in investigating it is compelled to use hypotheses, and does not go to a beginning because it is unable to step out above the hypotheses. And it uses as images those very things of which images are made by the things below, and in comparison with which they are opined to be clear and are given honor. |

A geometer, for example, draws on paper a right triangle, which is a visible form (horomenos eidos), but which as such belongs to segment B, i.e. a concrete diachronic object through which the synchronic invisible right triangle proportionality in the abstract shows itself, and which can thus produces furthermore an image of itself in mirror as when the geometer lifts up the paper in front of a mirror. When he makes arguments (logoi) about this right triangle, such as the Pythagorean theorem legs a2 + b2 = hypotenuse c2, he certainly is not thinking about the right triangle he has drawn on paper, which is usually just an approximate, i.e. inaccurate, representation of the invisible right triangle in the abstract (in synchrony) -- a representation whose sides probably do not perfectly conform to the theorem; rather he is thinking about that perfect right triangle in the abstract. Note that the right angle, the different types of triangles, the types of numbers used to calculate the theorem (odd and even), and whatever other properties of mathematics, the geometers take as given, simply parts of nature or reality about whose origin they do not enquire: "These things they make hypotheses and don't think it worthwhile to give any further account of them". They are only interested in discovering further properties of this and every right triangle not already known, such as the Pythagorean theorem. Taking the elements of geometry as given, without enquiring about why these elements are as they are or whence they come, and being interested only in discovering further properties of relations among these elements, thus the geometers are said to be investigating on the basis of hypotheses (the elements as "presuppositions") and making their way not to a beginning (arche: the synchronic origin, the reason why these elements are as they are) but to an end (the newly discovered, previously unknown, necessary proportionality among the sides of any right triangle: the Pythagorean theorem). And they do not enquire the origin of these elements ("go to a beginning") because they are unable to step out above these elements of geometry and arithmetics ("hypotheses"). It is for this reason that, even though the mathematical objects of the geometers are theoretically speaking forms, Glaucon, after understanding Socrates, has to make the statement about the inferiority of the Greek "mathematicians" of the time to the eidetic philosopher:

| aiV [tecnaiV] ai upoqeseiV arcai kai dianoiai men anagkazontai alla mh aisqhsesin auta qeasqai oi qewmenoi, dia de to mh ep'archn anelqonteV skopein all'ex upoqesewn, noun ouk iscein peri auta dokousi soi, kaitoi nohtwn ontwn meta archV. dianoian de kalein moi dokeiV thn twn gewmetrikwn te kai thn twn toioutwn exin all'ou noun, wV metaxu ti doxhV te kai nou thn dianoian ousan. (511 d) | The beginnings in the [geometric] arts are hypotheses; and although those who behold their objects are compelled to do so with the thought [dianoia] and not the senses, these men -- because they don't consider [look, study] them by going up to a beginning, but rather on the basis of hypotheses -- they don't seem to you to possess intelligence [nous] with respect to the objects, even though these objects are, given a beginning, intelligible; and you seem to me to call the habit of geometers and their likes thought [dianoia] and not intelligence [nous], indicating that thought is something between opinion [doxa] and intelligence [nous]. |

In other words, the mathematician, in taking the (mathematical) forms as the steppingstones most readily available for his ascendance in (mathematical) knowledge but as something whose source and way of being are a matter of indifference, although he is theoretically speaking taking hold of a (mathematical) portion of what is, does not understand it ("has no intelligence with respect to it") because he disregards its source, and this because he is not concerned with how he may know in the first place but only with how much he can know from there onward. The philosopher operative on segment D, however, will be different.

| To toinun eteron manqane tmhma tou nohtou legonta me touto ou autoV o logoV aptetai thi tou dialegesqai dunamei, taV upoqeseiV poioumenoV ouk arcaV alla twi onti upoqeseiV, oion epibaseiV te kai ormaV, ina mecri tou anupoqetou epi thn tou pantoV archn iwn, ayamenoV authV, palin au ecomenoV twn ekeinhV ecomenwn, outwV epi teleuthn katabainhi, aisqhtwi pantapasin oudeni proscrwmenoV, all'eidesin autoiV di'autwn eiV auta, kai teleutai eiV eidh. (511 b - c) | Well, then, go on to understand that by the other segment of the intelligible I mean that which the argument [logos] itself grasps with the power of dialectic, making the hypotheses not beginnings but really hypotheses -- that is, steppingstones and springboards -- in order to reach what is free from hypothesis at the beginning of the whole. When it has grasped this, argument now depends on that which depends on this beginning and in such fashion goes back down again to an end; making no use of anything sensed in any way, but using forms themselves, going through forms to forms, it ends in forms too. |

That is, when the philosopher intellect-ively sees the forms, he does not take these for granted as does the mathematician the mathematical objects which are forms also; rather he investigates whence the forms come, i.e. what the condition of possibility for these forms is, and in this way he comes to that condition of possibility, the ground, the "beginning" (arche), for all forms, which is, as seen, the form of the Good, which, as the final resting place for the soul, is not itself dependent on another form as its condition of possibility. This is how he does not mistake presuppositions (other forms, "hypotheses") as "beginnings" but arrives at the real beginning of all which must necessarily be "free from hypothesis" (a-hypothetical, not-presupposed). But now, having known the ground for all forms, he can come back to these forms again and understand them better than before as he can now see them against their source. In the context of the Republic, Socrates attempts to understand the forms of wisdom, courage, moderation, and, above all, justice (dikaiosune) against the form of the Good.

We take note for now that although Plato's "dialectic" as the explicitation of the inner meaning of forms seems to the moderns like a project of dictionary style definition just as does the Confucian eidetic equivalent of the "rectification of names", it is in fact a pre-scientific scientific project as we have seen, and that his ideal of going through forms without using images of them at all -- quite unlike the geometers -- is exactly the ideal the practitioners of classical mechanics try to achieve: whereas in the beginning of mechanics such figures as Descartes and his contemporaries and even Fermat later still depend on geometric figures and also the Cartesian coordinate to arrive at such "ends" (teleutai) as the velocity, momentum, and acceleration of a falling object, by the time of its mature period such figure as Lagrange has completely dispensed with any geometric or coordinate (i.e. 2 dimensional) representation of the kinematics of the objects and arrived at all conclusions ("laws", such as the Lagrangian [kinetic energy of the system]) by algebraic means (1 dimensional representations) alone.

2. The proportionality of the divided line. After naming the parts of the divided line, Socrates prescribes the proportionality of the divided line in accordance with the previously stated image-original relationship.

| kai oti ousia proV genesin, nohsin proV doxan, kai oti nohsiV proV doxan, episthmhn proV pistin kai dianoian proV eikasian. thn d'ef'oiV tauta analogian kai diairesin dichi ekaterou, doxastou te kai nohtou, ewmen, w Glaukwn, ina mh hmaV pollaplasiwn logwn emplhshi h oswn oi parelhluqoteV. (534 a5) | And as being is to coming-into-being, so is intellection to opinion; and as intellection is to opinion, so is knowledge (episteme) to trust (pistis) and thought (dianoia) to imag-ination (eikasia). But as for the proportion over which these are set and the division into two parts of each, the opinable and the intelligible, let's let that go, O Glaucon, so as to not run afoul of arguments many times longer than those that have been gone through. |

Sallis spells out the proportionality so far prescribed and then the consequences of Socrates' prescription:

prescription: (D + C) : (B + A) :: D : C :: B : A

consequence: D : B :: C : A

also: [(A + B) : B :: (C + D) : D]

|

"This result is, in fact, stated explicitly by Socrates in his third statement of the divided line (534 a). But the other result, that the middle two segments are of equal length (B = C) is not explicitly stated. This second result is especially curious, for clearly the general sense of the entire discussion of the line requires us to suppose that segment C (representing something belonging to the intelligible) involves a higher degree of clarity than segment B (representing something belonging to the visible). This means that there is a conflict between the proportionality which Socrates prescribes for the line and his stipulation that the divisions correspond to the degrees of clarity of what is represented. The line which he instructs Glaucon to draw, but which, in contrast to his procedure with the slave boy in the Meno (82 b), he apparently does not draw, cannot, strictly speaking be drawn." (p. 414 - 5) Hence Socrates' advice to "let go".

3. Education (illusion-overcoming) as the upward movement on the divided line. Sallis furthermore reminds us that the divided line "is a more adequate image [than the analogy with the sun]: it represents the visible and the intelligible as segments of a single continuous line rather than as two separated domains." (Ibid.) In other words, the double-sidedness of the divided line (subject-object) is meant to convey that "there is a correspondence between the participation of the affections of the soul in clarity and that of the things in truth (511 e)", which means that "for the degree of clarity definitive of a specific kind of condition in the soul there corresponds on the side of things the same degree of participation in truth. Thus, strictly speaking, what corresponds to the various conditions of the soul are various degrees of participation in truth on the side of what becomes manifest to the soul in that condition... [T]his can only mean that the fourfold division of things corresponding to the division on the side of the soul is not a division into four different regions of ultimately distinct things but rather a division into four different levels of participation of things in truth. Yet, for something to participate in truth means to become manifest as itself, and so, in different terms, the division on the side of things is a division into different degrees, different levels, of manifestness. Furthermore, something becomes manifest as itself precisely to the extent that it shows itself as one. What we have on the side of things are different levels of showing, four modes in which the same things can show themselves [more and more clearly, more and more as one], just as, on the side of the soul, one and the same soul can apprehend things with different degrees of clarity... the things corresponding to intellection are the 'same' as these things [in the visible, such as shadows, animals, and artifacts], but in a different, a more truthful, mode of showing." (p. 417) This sameness between the intelligibles and the visibles, Sallis maintains, is the reason why the middle two segments B and C are of the same length, for which he cites 31 c - 32 a in Timaeus as evidence.1

When, for the purpose of salvation, the soul moves upward along the line -- as it is supposed to, Socrates advises -- this means that the soul comes to see reality more and more clearly, more and more as itself. This upward movement is easy and a everyday activity of the common people below the level of the intelligible, within the level of the visible, but common people are usually stuck by the division between the intelligible and the visible. "[W]hereas the kind of images belonging to the level of eikasia [reflections in mirrors or water] are almost always recognized by us as images, whereas at this level we almost always have the original (and, hence, the distinction between original and image) already 'in view,' this is by no means the case at the higher level. We have not always already recognized the visible things as images of invisible things to be apprehended only by dianoia; that is, we do not always already have the intelligible 'in view.' On the contrary, we come to rest in the visible, so that the distinction between visible and intelligible is not immediately manifest." (p. 428) The second difficult hurdle is that between the mathematical objects of dianoia and the eidoi of noesis, as shown by the geometers' frequent inability to "go to the beginning" of the mathematical elements ("hypotheses") and "give account of them." The upward movement therefore depends on the provocation of the soul to cross these two hurdles and go up.

What this means is that, with respect to the first hurdle, the boundary between the visible and the intelligible, as Socrates notes, "some things of perception-sensation do not summon the intellect [noesis] to the activity of investigation" (523 b; ta men en taiV aisqhsesin ou parakalounta thn nohsin eiV episkeyin) and therefore do not lead the soul upward, "because they seem to be adequately judged by the senses" (wV ikanwV upo thV aisqhsewV krinomena), thus trapping the soul in contentment, in rest, "while others bid it in everyway to undertake a consideration" (ta de pantapasi diakeleuomena ekeinhn episkeyasqai) and therefore lead the soul upward because the senses in these cases seem to break down.

| Ta men ou parakalounta... osa mh ekbainei eiV enantian aisqhsin ama. ta d'ekbainonta wV parakalounta tiqhmi, epeidan h aisqhsiV mhden mallon touto h to enantion dhloi. (523 c) | The ones that don't summon the intellect... are all those that don't at the same time go over to the opposite perception. But the ones that do go over I class among those that do so summon, when the perception doesn't indicate a "this" more than its opposite. |

Those that do summon are those in which a mixed showing of mutually incompatible eidoi occurs: "Isn't it necessary that in such cases the soul be at a loss as to what this sensation indicates by the hard, if it says that the same thing is also soft, and what the sensation of the light and of the heavy indicates by the light and the heavy, if it indicates that the heavy is light and the light heavy?" (524 a; Oukoun... anagkaion en ge toiV toioutoiV au thn yuchn aporein ti pote shmainei auth h aisqhsiV to sklhron, eiper to auto kai malakon legei, kai h tou koufou kai h tou bareoV, ti to koufon kai baru, ei to te baru koufon kai to koufon baru shmainei;) As Sallis notes, such mixed showing most frequently occurs during situations of comparison, as when Socrates uses the example of the three fingers (index, middle, and the smallest finger) to illustrate the occasion of "summoning" (523 c). "He explains that when each is considered just as a finger, i.e., in that respect in which they are all the same, then dianoia is not provoked;... it is provoked only when one looks at the fingers in relation to one another and especially in contrast to one another. Specifically, the index finger appears big in relation to the smallest finger and small in relation to the middle finger, hence, both big and small; likewise, it appears thick in relation to the smallest finger and thin in relation to the middle finger, hence both thick and thin. More precisely, the kind of situation which provokes dianoia is that in which one of the fingers appears as a member in two pairs and such that it has one or the other of opposite qualities depending upon which pair it appears in. So, the kind of situation which provokes dianoia is that in which things appear in pairs, in dyads, and in which they are determined (e.g., with respect to size) only within such pairs..." (Sallis, p. 429 - 30) Once the dianoia is provoked in this way, it goes on first of all to separate the forms that are mixed up in the empirical object:

|

EikotwV ara... en toiV toioutoiV prwton men peiratai logismon te kai nohsin yuch parakalousa episkopein eite en eite duo estin ekasta twn eisaggellomenwn.

Oukoun ean duo fainhtai, eteron te kai en ekateron fainetai; Ei ara en ekateron, amfotera de duo, ta ge duo kecwrismena nohsei. ou gar an acwrista ge duo enoei, all 'en.Mega mhn kai oyiV kai smikron ewra, famen, all 'ou kecwrismenon alla sugkecumenon ti.Dia de thn toutou safhneian mega au kai smikron h nohsiV hnagkasqh idein, ou sugkecumena alla diwrismena, tounantion h keinh. (524 b - c5) |

... it's likely that in such cases a soul, summoning calculation and intellect, first tries to determine whether each of the things reported to it [i.e. the forms showing up] is one or two.

If it appears to be two, won't each of the two appear to be different and to be one? Then, if each is one and both two, the soul will think the two as separate. For it would not think the inseparable as two but as one. But sight, too, saw big and little, we say, not separated, however, but mixed up together... In order to clear this up the intellect was compelled to see big and little, too, not mixed up together but distinguished, doing the opposite of what the sight did. |

Again, this tells us that the essence of the form is that each is always one, and that "dianoia is, first of all, a distinguishing which separates the provocative mixture into distinct 'ones,' each taken by itself, and which poses these 'ones' in their distinctness over against the mixture. This posing of the distinct 'ones' over against the mixing-up of opposites presented by sight constitutes the originary opening up of the distinction between visible and intelligible. In fact, the description of dianoetic activity that we just cited concludes by making this explicit: 'And so, it was on this ground that we called the one intelligible and the other visible.'" (Sallis, p. 431) In the modern structural perspective, from what we have said, this awakening of dianoia -- which is the beginning of "education" (paideusis) -- corresponds to the distinguishing of the synchronic "laws" -- which are always each one, and as such distinct -- within the diachronic phenomenon in which they show up usually mixed up but whose intelligibility they, in thus showing, make possible: whether in economics, political sciences, linguistics, or the physical sciences, the object is always to achieve the dianoetic consciousness of the phenomena under study by discovering the "laws". We have used specifically as examples linguistic typology and physics. In all (diachronic) pronouncements of English the modified-modifier (synchronic) logic (eidos) shows up mixed up with its opposite, the modifier-modified, even though the former prevails on the large-scale (sentence level): "I don't like my constantly whining, finger-sucking, fail-to-grow-up brother who somehow thinks himself to be such a hot-shot." Here the modified-modifier logic shows up as the SVO sentence structure and postposed relative clause but the modifier-modified logic also shows up as the adjectival phrase-noun structure. The opposite logics of word-order on the level of eidoi (D), first manifesting themselves in clausal structures (modified-modifier in VO and modifier-modified in OV), noun-phrase structures (in noun-adjective and in adjective-noun, respectively), appositional structures (in preposition and in postposition, respectively), etc. on the level of C, then show up confusedly on the level of pistis as the words we hear which can further be copied or transcribed on paper which is the level of eikasia. Under the provocation of the typological confusions present in the actual pronouncements in diachrony (B) the noesis is supposed to separate each of the two logics of word-order as one and distinct from the other: thus doing linguistic typology. In the previous physics example of the accelerating cart with a metal ball hanging from a string tied to the cart's ceiling (level B), of which reflections can be seen in water or mirror (A), we see similarly that the first step of a quantitative description of the phenomenon ("doing physics problem") is to distinguish the eidoi F = ma, the trigonomic functions, and weight (C) -- which when one works through them one would discover to be reducible to one another or to other forms (as weight = mg = a variant of ma, and g leading to Newton's law of universal gravitation G(m1m2)/(r2): all this on level D: "going through forms to forms, noesis ends in forms too.") Hence Sallis reminds that "dianoia not only distinguishes the ones but also relates them. The most obvious sort of relation that it establishes in its beginning is that of opposites to one another" (ibid.): e.g. the modified-modifier logic is the opposite of the modifier-modified.

As the "soul" (or consciousness, mind, in today's structural perspective) has crossed the hurdle between the visible and the intelligible -- the division between the two becoming in the process manifest to it as well -- such as when a college student starts studying and understanding linguistic typology or classical mechanics, there is still the second hurdle, that between dianoia and episteme, to cross. How does the soul accomplish this? To understand this, let's look at how Socrates names one by one the fields of study that the soul has to go through in order to accomplish the upward movement from the visible to the Good.

dialectic (philosophy)

^

|

astronomy

^

|

3 D geometry

^

|

2 D geometry

^

|

arithmetic

Education: the upward way

|

The purpose of education -- and of science -- is, as Socrates repeatedly emphasizes, to draw the soul away from the diachronic, temporal world of coming-into-being-and-passing-away (tou pote ti gignomenou kai apollumenou) and turn it toward the synchrony of being-always (tou aei ontoV). The simplest study that would thus turn, i.e. summon dianoia, is arithmetics, since it starts with the concept "one" -- and the study of the one is apt to lead and turn around the soul toward the contemplation of what is (525 a; (kai outw twn agwgwn an eih kai metastreptikwn epi thn tou ontoV qean h peri to en maqhsiV), and similarly with all numbers (525 a 6) -- and since it is the arts of calculation (logistikh) and number (ariqmhtikh) that are both wholly concerned with number (525 a 9). But here Socrates indicates how to overcome the second hurdle: the person must study it, "not after the fashion of private men, but to stay with it until they come to the contemplation of the nature of numbers with intellection itself (... kai anqaptesqai authV mh idiwtikwV, all'ewV an epi qean thV twn ariqmwn fusewV afikwntai thi nohsei authi), not practicing it for the sake of buying and selling like merchants or tradesman." (525 c) In other words, one must study theoretical mathematics and physics for their own sake, in order to understand the derivations until the underivable "beginning", and not applied mathematics or physics for the sake of engineering. This is how dianoia can transform itself into episteme -- going all the way to the "Theory of Everything" (the "beginning"): once the soul (mind) reaches the synchronic-intelligible, it shall not descend back down to the diachronic-visible in order to understand or manipulate the objects there better ("engineering"), but shall keep going up (c.f. Sallis, p. 432 - 5).

The soul shall then study 2 dimensional geometry, again theoretical and not applied; then 3 dimensional geometry, dealing with solids rather than planes; then astronomy, "which treats the motion of what has depth" (... astronomian... foran ousan baqouV), i.e. adds the fourth dimension of time to the three dimensional. Pay special attention to Socrates' comment about the proper object of astronomy: those moving planets "fall far short of the true ones, those movements in which the really fast and the really slow -- in true number and in all the true shapes -- are moved with respect to one another and in their turn move what is contained in them. They of course must be grasped by argument and thought, not sight." (529 d; ... twn de alhqinwn polu endein, aV to on tacoV kai h ousa braduthV en twi alhqinwi ariqmwi kai pasi toiV alhqesi schmasi foraV te proV allhla feretai kai ta enonta ferei, a dh logwi men kai dianoiai lhpta, oyei d'ou.) In other words, falling or moving itself, not of this and that. Arithmetics and geometry being specifically Hellenic development, it is quite fitting that the Renaissance Europeans rediscover Plato, for soon afterwards Galileo has isolated "falling" itself (d = 1/2at2) and then Newton has grasped the "moving" behind all movings due to gravity with his law of universal gravitation: Plato's astronomy at last realized. But one does not finally transcend segment C until one reaches the final study, dialectic, or eidetic study (of forms), which is philosophy, but which in the modern structural perspective would be doing theoretical physics (until the theory of everything) but with the philosophical bent: i.e. the scientific enlightenment to be seen.

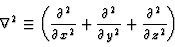

Note also how Plato's continuous addition of dimension to geometry (from 2 D to 4 D) during the ascendancy corresponds to the actual evolution of classical mechanics: Newton's F = ma is essentially for objects moving with 1 degree of freedom (in 1 dimension); by Lagrange and Laplace the basic equation is for the kinematics of the moving object with 3 degrees of freedom (3 dimensional: x, y, and z axes of Cartesian coordinate) or more. Ontogeny shows up in phylogeny, and classical mechanics, as the quantitative study of objects in motion ("astronomy"), picks up where Plato left off but repeats in its evolution the evolution of geometry:

| F = ma = | m | d2x dt2 | => (Lagrange) | m | d2x dt2 | + | m | d2y dt2 | + | m | d2z dt2 |

| => (the Laplacian scalar differential operator) |  |

4. The contemporary equivalent of the upward movement toward dialectic. Recall that what Plato was doing back then (in the functional perspective) with all this theory of forms and divided line, if transposed to today (into the structural perspective), would simply be the scientific project (from physics through chemistry to linguistics: eidetic study = science), and that, insofar as Plato did all that study of forms and logos about the divided line -- insofar as the purpose of doing philosophy was -- for the sake of eternal salvation, knowing how for Plato the dialectic might lead to eternal salvation would show us how today the study of science can lead to such salvation (the project of scientific enlightenment).

What we're trying to say here is that the object of "dialectic" today is the structure of reality as such, i.e. from the periodic table "up" through the standard model of elementary particles to the "theory of everything". It must reach a self-evident "beginning" -- strings or not -- from which all later equations of quantum theories and general relativity can be deduced, i.e. accounted for: "And do you also call that person dialectical who grasps the reason [logos] for the being [i.e. form] of each thing? And, as for the man who isn't able to do so to the extent he's not able to give an account [logos] of a thing to himself and another, won't you deny that he has intelligence with respect to it?" (534 b 3 H kai dialektikon kaleiV ton logon ekastou lambanonta thV ousiaV; kai ton mh econta, kaq'oson an mh echi logon autwi te kai allwi didonai, kata tosouton noun peri toutou ou feseiV ecein;) Socrates calls those latter who can't account for the later equations ("hypotheses") -- in his case the geometers -- merely "dreaming about what is" (wV oneirwttousi men peri to on); these "hypotheses" or equations standing alone arbitrarily (or rather the 20 something parameters in the standard model that need to be posited by hand rather than being deduced in order for the observed universe to show itself as it is) he calls mere "agreements": "When the beginning is what one doesn't know, and the end and what comes in between are woven out of what isn't known, what contrivance is there for ever turning such an agreement into knowledge?" (533 c; wi gar arch men o mh oide, teleuth de kai ta metaxu ex ou mh oiden sumpeplektai, tiV mhcanh thn toiauthn omologian pote episthmhn genesqai;)

The study of the structure of reality is grasping "about each thing itself what each is." (533 b; wV autou ge ekastou peri o estin ekaston.) That is, grasping the entirely synchronic aspect of reality. But when this dialectic is transposed to modern time, there are changes in this respect. First of all, the grasping of the synchronic laws (such as Maxwell's 4 equations of electromagnetism showing up in electromagnetism), when going toward the beginning (such as when this law of electromagnetism is united with that for the weak force), actually shows how the diachronic reality (the universe) evolves through time (the breaking of symmetry between electromagnetism and the weak force 10-12 second after the creation of the universe). The modern "dialectic" does not simply show why things around show themselves as they are (all that Plato was doing) but also explains where they came from: a time-dimension has been added. Plato himself is to add the time-dimension in his Timaeus.

Secondly, the peculiarity of the functional perspective in which Plato constructs his eidetic study is that human values and the objective (i.e. geospheric) structure of reality are compacted together, so that the former are taken to be ingrained in the latter. The way Plato "grounds" human values in the geospheric structure of reality is through the teleological conception of the cosmos, so that the idea of the Good can not only serve as the "beginning" (origin) for the forms of "bigger", "smaller", all the numbers, and all other forms making intelligible the physical aspect of reality, but also as the "end" (which is to say, the "beginning") for all human values ("justice is good", "courage is good", "pleasure is good in such and such circumstances"). Today the teleological notion of the universe has broken down, unless one subscribes to a value-ridden version of the anthropic principle such as that of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. That "facts" and "values" do not imply each other is the rule today. In this work we have traced the origin of human values in the objective, physical reality, but this time in the thermodynamic structure of the universe ("Origin of Good and Evil"). Such genealogy of course can be re-used to argue that the physical reality does specify what is right and what wrong, and what good and what bad, but such leap from "is" (that humans have constructed their values in reaction to the problem of order-formation within the thermodynamic universe) to "ought" (that therefore their values are rightly ordained by the universe) is not the intention of my genealogy. What all this means specifically is that Plato's dialectic, when transposed to today's structural perspective, is not the theory of everything, just as the Theory of Everything sought for in physics is not the theory of everything but only the theory of everything in the geosphere. A theory of biosphere and the noosphere needs to be added to complete the "dialectic".

Thirdly, as said, modern physics itself is not "groundless", but presupposes the worldhood (Weltlichkeit) whose decontextualization into presence-at-hand (Vorhandenheit) makes possible the eidoi known as the equations of classical mechanics. (This we'll explore in the study of the history of mechanics in "The Problem of Representation".) Plato's forms are given ground in the idea of the Good through the teleological conception of the cosmos, but today this eidetic structure of reality breaks up into Weltlichkeit on the one hand and physics and chemistry on the other. The upward movement in the structural perspective consequently has to change. Starting from the immediate perception of reality, the "soul" (mind) must move into the analysis of worldhood first (Division One of Heidegger's Sein und Zeit) and go to the "beginning" for worldhood in temporality (Zeitlichkeit) and Dasein's self-interpretive way of being; and only then shall come to classical mechanics, chemistry (unified in the periodic table), the new (post-classical, quantum) physics, and finally to the beginning for these in the "Theory of Everything". Illusion is broken, or overcome, first during the transition from Heidegger's Daseinsanalytik to classical mechanics and chemistry (corresponding to the transition from pistis to dianoia), and finally during the transition to the new physics (corresponding to the transition from dianoia to episteme or nous).

|

Dasein ---> | -->| "Theory of Everything"

^ | | ^

| | | | ------ transition (2)

| | | |

immediate | | | (classical) periodic

reality --------> Weltlichkeit | -------> physics -- table

|

transition (1)

|

The "transition", the overcoming of illusion, which is "education", is to be graphically illustrated with the allegory of the cave, which, as Sallis notes, "unites the sun analogy and the divided line".

Footnote:

1. C.f. Sallis' footnote 58, p. 417. Sallis also notes that the divided line is itself an image of the invisible divided line -- and, as such, corrupted, whence the contradiction in the drawing of it posed by the equality between B and C: "Thus, at the level of eikasia there is the image of the line which Socrates presents in the form of a verbal description. This image leads us to draw the line, to produce the visible thing of which the verbal description is an image, and thus we pass to the level of pistis. But then, in reference to the drawing (taken as a visible image) we try to formulate mathematically the various proportions that define the line; and thus we seek to take the measure of the line, to clarify it, by the way of a downward-moving dianoia. However, this clarification proves to be... impossible... there is a conflict between the original proportion and the stipulation that the length of each segment should correspond to the degree of clarity and truth that characterizes that level. Granted this stipulation, the middle segments cannot be equal in length -- or, in another sense, they could be equal only for one who remained stuck at the level of downward-moving dianoia." (p. 439 - 40) For another interesting discussion, c.f. "The political significance of the divided line", the Appendix to Darrell Dobbs' "The Justice of Socrates' Philosopher Kings" (1984). Especially: here he points out that if trust is the equal of thought, then "imaging is to trust as trust is to intellection and imaging is to thought as thought is to intellection. The intelligible continuity of the proportion imaged here is a nontautologous basis for the line's integrity, notwithstanding its visible appearance of discontinuity" (p. 825).

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |