|

Scientific Englightenment Div. One Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.3. Chapter 5: Germanic (esp. Anglo-Saxon) Religion ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Englightenment Div. One Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.3. Chapter 5: Germanic (esp. Anglo-Saxon) Religion ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

Copyright © 2000, 2004, 2005 by Lawrence C. Chin. All rights reserved.

The structure that we have worked out for "primitive religiousness" furnishes us with a way to understand such specific instance of it as the Germanic (with a focus here on the Anglo-Saxons), and therefore to read, interpret, and understand such sources of information as Gale Owen's Rites and Religions of the Anglo-Saxons (1985) and Edgar Polomé's "Germanic Religion" (Encycl. of Rel., vol. 5, p. 520 - 536).

1. The Germanic anima system. That is, the gods. The Germanic gods were specialization of the Proto-Indo-European system of Anima. The supreme deity of Indo-European inheritance, the sky god (*Deiwos), remained as Tiw (or Tiwaz, for whom Tuesday is named: OE Tiwes-daeg), but no longer as the supreme deity (unlike its cognates Zeus and Jupiter), only as a god of battle. Human sacrifices were however still offered to him. (Owen, p. 28) Its animal associate (the manifestation of its anima? In any case the looser form of the "totem") was the horse. "Dr. Ellis Davidson has suggested (Gods and Myths, p. 60) that Tiw was identical with the god known as Seaxnet" or Saxnot. (p. 30) The Germanic specialization had the gods divided into two families, the AEsir and the Vanir, the former usually related to war and the latter to fertility (such as of soil): the two areas on the success in which the survival of the group depended. The supreme deity was now Odin (or Woden, from which comes Wednesday: OE Wodenes-daeg), nicknamed Grim ("which apparently arose from the belief that the god habitually appeared in disguise (OE grima: a mask, visor or helmet)"; p. 10). In terms of etymology Odin, more than Tiw, derives directly from the primordial experience of divinity as the breath-soul blended into the atmosphere: it came from Old Norse ond, "breath"; "Othinn's name (Germanic, *Wothan[az]) derives from a root meaning 'to blow' and includes the connotation 'life-giving power' in some of its derivations." (Polomé, p. 527.) The atmosphere, as the Ancestral Anima (the god Odin), animates and nourishes all life, so that in the Germanic myth of the creation of man, the Voluspa, Odin, and his two other hypostases, Hoenir and Lothurr, created man from two tree trunks and by imparting the breath of life into him. (Ibid.) The atmospheric Anima may at times blow wind furiously: "The Germanic stem of his name, *woth-, also appears in German as Wut ('rage'). Adam and Bremen thus correctly interpreted Othinn's name as 'furor' when describing the pagan gods in the temple at Uppsala." (Ibid.) As said, if the original experience of "animation" of the organism by the atmosphere produces thus the conception of the breath-soul as also compacted of consciousness and metabolism, one should not be surprised to find that Odin, with his hypostases, also came to acquire the connotation of sense, feeling, intelligence and movement ("the second god [Hoenir] endows man with vit and hroering ('wit and movement')..."). (Ibid.) The AEsir (traceable to the Old English word os, "god"; Owen, p. 12; or possibly cognate with the Old Indic prefix asu-, "breath of life"; Polomé, p. 529) was the family of Odin/Woden. As a god of warriors according to Norse mythology, he chose, through his agents the Valkyries (choosers of the slain), "from those fighting in a battle, who were to be victorious and who slain." (Owen, p. 13.) Half of those slain he collected "to serve as his einherjar in Valhalla [below]", Freyja, from the Vanir, collecting the other half (p. 533). From Woden most Anglo-Saxon royalties (especially the Anglian kings) traced their ancestry. (On the other hand the Saxnot "was claimed as an ancestor by the Anglo-Saxon kings of Essex (the East Saxons). Theirs is the only surviving Anglo-Saxon royal genealogy to go back to Seaxnet rather than Woden... Dr. Dumville argues that originally Seaxnet may have been acknowledged [as the ancestor] by all the Saxon tribes"; p. 30.) Elsewhere Odin, as receiver of human sacrifices, may be identified with "the regnator omnium deus ("god reigning over all") venerated by the Suevian tribe of the Semnones in their sacred grove and honored as their ethnic ancestor with regular human sacrifices", though he might "have been worshiped as an eponymous founder under the name *Semno." (Polomé, p. 531.) "According to the Old Icelandic poem Havamal Woden/Odin was hanged on a tree for nine days and nights, pierced with a spear, a voluntary sacrifice, as a result of which he learned wisdom, the secret of runes" (p. 11). As we have seen, the acquisition of supernatural power via self-mortification (including fasting) works either through the karmic chain of causation or by energetic saving. As a result of this, not only was the runic alphabets accredited to Woden/Odin but human sacrifices offered to him were stabbed and hanged. We will see below that Odin, in accordance with his nature as the primary atmospheric Anima, also decreed cremation and the spirits of those cremated (e.g. the Anglian royalties) "went back to him" (rejoining the Ancestor).

The others of AEsir included Woden's consort Friga or Frigg (from which Friday, OE Frig-daeg), the goddess of childbirth and marriage, of passion, with "foreknowledge and skill in magic", reflecting the general prescience which the Germanic people respected in women; and Woden's son Thunor (whence Thursday, OE Thunres-daeg), "a god of simple physical strength, associated with thunder... He habitually carried a short-handled hammer... he used it to restore his goats to life, having eaten them, and to consecrate a bride" (p. 25). God eats of (so to speak) himself, as in sacrificial offerings, to regenerate himself -- to be able to produce more of animalia. "The swastika symbol was also associated with Thunor, perhaps as a representation of the lightning he created." (p. 25) Then there was Balder, also a son of Woden (according to late Norse sources, p. 25), with the story of death and near resurrection.

On the side of the Vanir were the main fertility gods Ing and Freyr, possibly identical with one another. While the sacred horses "were linked with Freyr in Scandinavia, Freyr and his twin sister Freyja were both associated with boars." (p. 31) We'll see more of the twin and of their other animal associations below. Freyr's father was Njord, "who controls the path of the wind and, as sea god, counteracts the effects of the thunderstorms, quieting the sea and smothering the fire." (Polomé, p. 533 - 4) Worshipped also was the Mother Earth, such as Nerthus among many Suebian peoples. Tacitus offers few details about her: "she remains hidden in a curtained chariot during her peregrinations among her worshipers; only her priests can approach her, and after the completion of her ceremonial journey she is bathed in a secret lake, but all those who officiate in this lustration rite are drowned afterward to maintain the 'sacred ignorance' about her." (Polomé, p. 531) "Tacitus [furthermore] (Germania, 45) mentions that the Germanic tribes called Aestii cultivated crops and worshipped the Mother of the gods (presumably a fertility symbol), in whose honour they wore boar masks instead of armour." (Owen, p. 31) This was presumably some sort of cosmogonic re-enactment to regenerate the vitality, hence fertility, of the cosmos. In any case such theme was behind the heathen new year beginning on 25 December, called modranect, "or in Latin matrum noctem -- 'Mother's Night'... Mother's Night may have acknowledged the cult of Mother Earth to ensure fertility in the coming spring season." (p. 34). Votive stones from the territory of Ubii on the left side of the Rhine in the second or third centuries CE. also mention matres, or matronae. (Polomé, p. 532) The "Mothers", or Norns, seem to exist in a trinity. Another fertility goddess indicated by the inscriptional material of the Roman period was Nehalennia, with attributes of cornucopias, specific fruits, dogs, and "whose sanctuary near Domburg in Sjaeland has yielded an abundance of altars and statues". (Ibid.) As fertility goddesses these -- matronae, Nehalennia -- not only were worshipped -- asked -- to offer prosperity for the family and protection against danger and catastrophes -- remember that in primitive religiosity the breakdown of the cosmos, as during natural catastrophes, was the result of the god's entropic breakdown due to the neglect of her worship, and the prosperity of the tribe the result of her healthiness due to the attentive care of her by humans -- but also determined, in this respect, in the case of matres, the fate of humans, and served as, in the case of Nehalennia, the patronage of navigation.

Without getting into details of Germanic cosmogony it may be mentioned in passing that Mannus ("man"), according to Tacitus' account of Germanic thinking (Germania 2), was taken to be the universal divine ancestor giving rise to the three sons that engendered the three principal Germanic groups of tribes: the Inguaeones, descending from Ing (*Ingw[az]), from the North Sea region; the (H)erminones, "whose territory extended from the lower Elbe southward into Bohemia"; and the Istaevones, of the Weser-Rhine area. (Polomé, p. 531)

As for the lesser gods, "Bede, in his treatise on Time, mentions two goddesses, Hreda and Eostre, equating Hredmonath with March and Eosturmonath with April." (Owen, p. 37; Eostre, possibly from *Austro, could have however been a Christian missionary term and so not native; Polomé, p. 533.) Also Geat, an ancestor god, probably "the tribal god of the Geat people, the race about to be conquered at the close of the partly fictional/partly historical poem Beowulf." (Ibid.) Then Heremond, a northern god. Hel, the goddess of the underworld of the dead. Note that "the dark hall of Hel... is not a place of punishment" (Polomé, p. 524), but a neutral underworld for the dead to go to. As "the lowest world where the wicked go", there was Nifhel, lying beneath all the worlds (ibid.). Two other mythical fertility figures that we shall encounter below are Sheaf (Sceaf, or Scef), a child who came over the ocean from nowhere to bring prosperity, and his son Beow, meaning "barley". (Owen, p. 32) "Sceaf was remembered as a great king in the literature and history of England, Denmark, and Iceland." (Ibid.) From him was derived Scyld Scefing ("shield with the sheaf", i.e. military might together with agricultural prosperity), "the legendary king whose career and ship funeral form the unforgettable prologue to Beowulf" (ibid.). Along with Woden Scyld, Sceaf, and Beow all figured in the legendary genealogies of Anglo-Saxon kings. In this connection, in the pre-migration Germanic world in general, the divine twins *Alhiz might also be mentioned, who were equated with the Roman Castor and Pollux and worshipped locally, especially among the eastern Germanic tribes, as ancestors. (Polomé, p. 531, 532.) After the migration, the "functional role [of the divine twins] is euhemerized in the figures of the twin founding heroes of various Germanic groups, such as Hengist and Horsa for the early Saxons in Great Britain, Raos and Raptos for the Vandalic Hasdingi, and Ibor and Aio for the Winnili (Lombards)." (Ibid., p. 532) In the Annals Tacitus also refers to Tamfana, whose "'temple' was allegedly leveled by the Romans during the celebration of an autumnal festival in 4 CE." (Ibid, p. 531) The Frisians had a goddess, Baduhenna, "near whose sacred grove a Roman detachment was massacred." (Ibid.) Fosite was another deity "to whom an island was consecrated at the juncture of the Frisian and Danish territories", and may be related to the Scandinavian Forseti. (Ibid, p. 533) The other gods that appear in the Germanic mythology passed down from Scandinavian sources (not analyzed here) include Hoenir, Lothurr, Loki, Thjazi, Mimir, Heimdallr, the archer god Ullr, the giants Suttungr and Belli, the goddess Ithunn, then Vili, Vé, and Ymir (the primal giant sacrificed by Vili and Vé to create the world from his body parts: the transmythological theme)...

The forces of entropic disintegration objectified apart from the "wrath of god" (such as when he was hungry) were personified among the Anglo-Saxons as: the men-eating thyrs, giant and demon, such as the monster Grendel Beowulf fought against (although not necessarily the entas (giants) "to whom [the Anglo-Saxons] attributed the creation of the great stone buildings which the Romans had left in Britain. The Anglo-Saxons, who in the first centuries after their immigration built only in wood, viewed these crumbling monuments of a superior civilization as eald enta geweorc (ancient works of giants)"; Owen, p. 65); the aelf (plural ylfe): hostile creatures bringing disease; dweorg (dwarf), another "unfriendly creature against which ritual actions and a metrical charm were employed" (ibid.); a kind of demon called succa; water monsters haunting the lakes; and finally dragon, such as Beowulf's final monstrous enemy, called wyrm and draca. Dragon seems everywhere to have derived from either worm or snake. "[T]raditionally, dragons were believed to live in barrows, guarding hoards of treasure" (p 90).

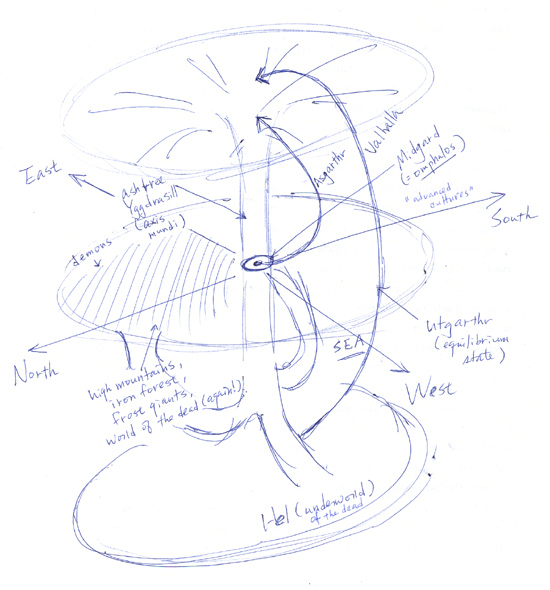

2. The spatiality of the cosmos: the axis mundi and the omphalos. The diachronic aspect of the worldview of the Germanic people -- the creation myth -- we do not deal with here, but only the synchronic aspect: "Man lives in the center of the universe; the major Germanic traditions concur in calling his dwelling place Midgard ("the central abode" [or the "middle-earth", exactly equivalent to the Chinese self-designation as the "middle-kingdom"]... OE Middangeard...). But the center is also the place where the gods built their residence, the Asgarthr... Outside is Utgarthr, the dangerous world of demons, giants... and other frightening creatures" personifying the forces of linear entropy (Polomé, p. 523). In other words, the Germanic mythical world is constructed in the same way as that of the Israelites or the Chinese or the Aztec or the Amerindians or any other peoples, i.e. according to the thermodynamic experience of order-formation: the omphalos in the center, the habitation of life as people know it, is the realm of order, i.e. "an island of low entropy in an increasingly disordered environment, hence precious and always endangered." In this way "Germanic myth evinces a real fear of this no-man's land outside the settlement, and the idea of the frontier is there all the time, with the [good, well-fed] gods serving to ward off dangers from the wild." (Ibid.) While this aspect (the omphalos) of the Germanic worldview is universal, the details of the Utgarthr -- "[t]he north and east [as] particularly dangerous abodes of demons;" the north, especially, "represented by high mountains", "'iron forest' (iarnvidr), where the brood of demons is born", and "frost giants (hrimthursar)" and as "the world of the dead" in addition to Hel; the south, as "the seat of advanced cultures", is given "a favorable connotation"; "in the west lies the big sea" (p. 524) -- are obvious reflections of the Germanic people's actual geographical location. In their later conception, however, the Asgarthr is transferred to heaven as the abode of the gods. In the new conception the meaning of Valhalla also changes. "Originally, it was a subterraneous hall for warriors killed in combat; later connected with Othinn, it becomes the heavenly residence of his heroic retinue, the einherjar. It is a huge palace with 540 rooms, each with a single door so large that 800 warriors exit through it to go and fight (Grimnismal 23 - 24)" (p. 524).

As mentioned, part of the experience of the omphalos is the cosmic tree, which manifests itself in the Germanic worldview in the symbol of the ash tree Yggdrasill, "where the gods sit in council every day", and which "rises to the sky, and its branches spread over the entire world. It is supported by three roots: one stretches to the world of the dead (Hel), another to the frost giants, and the third to the world of men." (Ibid.) That is to say, it is, as said, the connection between the world of the living and the world of the spirits, the axis mundi that not only stands in the center of the world as the source of its order but unifies all aspects of the cosmos that are not on the same plane of reality (the dead, the divine, the living profane), and has furthermore the function of propping up the sky to prevent the differentiated order of the cosmos from collapsing back into equilibrium. This idea was later on also manifested in the symbolism "Irminsul (or Saxon 'idol') destroyed by Charlemagne in 772 and described by medieval historians such as Rudolf of Fulda as a huge tree trunk." (p. 525) The Germanic Yggdrasill possesses the peculiarity of having at its foot three springs: the spring of the goddess of fate (Urthr: Voluspa 19), the wells or source of wisdom (Mimir: Voluspa 28), and the rivers of the world (Hvergelmir: Grimnismal 26). (Ibid.) "According to the Eddic poet, a clear vivifying liquid called aurr drips down continuously from the tree (Voluspa, 19)." (Ibid.)

3. Mediation, sacrifice, and temporality. In earlier times the Germanic peoples worshipped in groves, apparently without any representations of the deities; later the sacred groves were superseded by temples with idols in them, such as in England during the time of Christian mission (p. 41). In addition, "[English p]lace-name evidence suggests that hills were very often used for heathen temples." (p. 42) "It is more likely that the idols were pieces of wood on which carvers accentuated a natural resemblance to the essential feature of the 'god', as in a Danish example from an Iron Age site." (p. 42) An description of the interaction with the deity through the "pole" on the opposite side from England, in the case of the "Rus", is found, e.g. in "Ibn Fadlan’s account of his participation in the deputation sent by the Caliph al-Muqtadir in the year 921 A.D. to the King of the Bulghars of the Volga, in response to his request for help" (James Montgomery, "Ibn Fadlan and the Russiyyah"; Journal of Arabic and Islamic Studies 3 (2000); the translation of the Arabic is his):1

| The moment their boats reach this dock every one of them disembarks, carrying bread, meat, onions, milk and alcohol (nabidh) [probably made from fermented honey, not beer], and goes to a tall piece of wood set up [in the ground]. This piece of wood has a face like the face of a man and is surrounded by small figurines behind which are long pieces of wood set up in the ground. [When] he reaches the large figure, he prostrates himself before it and says, “Lord, I have come from a distant land, bringing so many slave-girls [priced at] such and such per head and so many sables [priced at] such and such per pelt.” He continues until he has mentioned all of the merchandise he has brought with him, then says, “And I have brought this offering,” leaving what he has brought with him in front of the piece of wood, saying, “I wish you to provide me with a merchant who has many dinars and dirhams [J. M. notes the "Rus fondness for Islamic silver"] and who will buy from me whatever I want [to sell] without haggling over the price I fix.” Then he departs. If he has difficulty in selling [his goods] and he has to remain too many days, he returns with a second and third offering. If his wishes prove to be impossible he brings an offering to every single one of those figurines and seeks its intercession, saying, “These are the wives, daughters and sons of our Lord.” He goes up to each figurine in turn and questions it, begging its intercession and grovelling before it. Sometimes business is good and he makes a quick sell, at which point he will say, “My Lord has satisfied my request, so I am required to recompense him.” He procures a number of sheep or cows and slaughters them, donating a portion of the meat to charity [J. M. notes: "The merchant probably held a feast of some sort"] and taking the rest and casting it before the large piece of wood and the small ones around it. He ties the heads of the cows or the sheep to that piece of wood set up in the ground. [We'll note the special significance of the animal head below.] At night, the dogs come and eat it all, but the man who has done all this will say, “My Lord is pleased with me and has eaten my offering.” |

As for who these deities of a family were which the wooden poles represented, Montgomery favours "Frey[r], of the Vanir, a god 'particularly associated with the Swedes' (Foote and Wilson, 389), a god generally held to be responsible for trade and shipping. His sister Freyja was the leader of the female divinities known as the Disir, 'who had influence on fertility and daily prosperity' (Roesdahl, 162). A sacrifice of an ox or a bull was most appropriate to Frey[r], who seems also to have been thought of as a bull, while his sister was thought of as a cow [more, below]... Jones and Pennick (A History of Pagan Europe, London, 1995, 144) on the other hand, associate Frey[r] with the horse and the pig." We immediately see that these wooden poles were the "mana poles", the artificially constructed regions where the anima-mana (in this case, of Freyr and his company) was especially concentrated. If we recall the overall structural field of sacrifice we have earlier isolated:

The above instance of offering, the sort of reciprocity captured in the formula do ut des, is a typical endergonic as the feeding of the gods to enable them to do certain things, or in energetic terms, the deposit of energy and its subsequent withdraw in some other energetic form (here a successful trade). The additional offering after the "return on the investment", which, with its concomitant "charity", reminds strongly of the Roman "daps... le repas offert après une consécration, repas de largesse, fête de magnificence", is still endergonic but, as thanksgiving, is to repair god's exhaustion after his "hard work" and which would result in his "anger" (entropic disintegration of the order of the cosmos or of society) if not remedied. The strongest, i.e. most nutritious, offering is of course the human sacrifice, which, as mentioned, the Germanic peoples (though not the post-migrational Anglo-Saxons?) periodically offered to their ancestor gods, such as Odin and Tiw. How the offering of the life of one's fellow tribesmen to the ancestral god helps to prevent his anger -- manifested as environmental catastrophes -- has previously been explained.

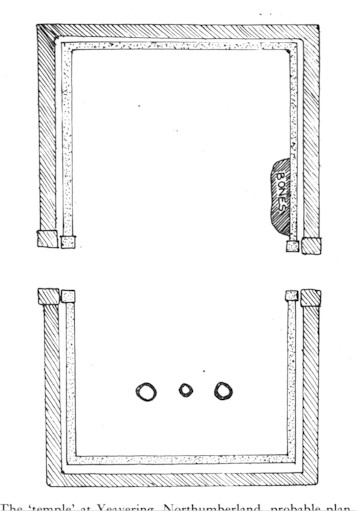

An example of heathen temple which started appearing by the time of Christian mission was excavated at Yeavering in Northumberland, "in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Bernicia, an area where the majority of the population were Celtic. The Anglo-Saxons were acknowledged as rulers in Bernicia during the sixth century and Yeavering became a royal dwelling-place from the reign of Aethelfrith in the first years of the seventh century." (p. 43; figure below.) Noteworthy here is a massive, high post outside the temple to the north-west, certainly with ritual significance, i.e. a mana-pole, equivalent to the Pacific totem poles (p. 43 - 4); and furthermore the pit by the door filled with the skulls of oxen. "To the west there was a building probably used as a kitchen for cooking the ceremonial feasts. Associated with this structure was an area apparently reserved for butchering the sacrificial beasts. It contained many remains of the long bones of oxen, but, significantly, not skulls -- they ended up in the temple" (p. 45).

A sacrificial formula is evident here: the body of the ox was for the communion feast of society but its head -- the seat of its spirit (anima) -- was given back to god himself: As mentioned, "[i]n Scandinavian paganism animals, particularly oxen, were offered to Freyr on his annual journey... The ritual sacrifice of oxen is a feature of Anglo-Saxon paganism evidenced repeatedly by archaeology and confirmed by historical document." (p. 45) What is evidenced here is another instance of "god eats god himself": the oxen were (sometimes) the materialization of the Freyr's anima and as such considered particularly nutritious, highly concentrated with energy. The society thus ate them to regenerate social order and Freyr himself ate them (or only their anima which was congruent with him) to regenerate his own order (the fertility of nature -- such as in the generation of crops -- which he represents), just as Brahman ate Brahman or the Egyptian gods ate Maat. (We have already mentioned the "re-fertilization" of the Mother Earth by magico-theatrical means at New Year.) The undifferentiated form of sacrifice of the ox (simultaneous communion feast to regenerate society and expiatory feeding of the god) signified thereby took place usually around November, the start of autumn, as "Bede (De Temporum Ratione XV) gave the English word blodmonath as the equivalent of November, explaining it: 'Blodmonath [was] the month of sacrifice because in it they dedicated to their gods [of fertility, Freyr and Freyja] the cattle which they were on the point of slaughtering' (Jones, p. 211, 213). In England in Anglo-Saxon days, and indeed until the agrarian revolution of modern times, the majority of cattle were slaughtered in the autumn and the carcasses salted as a winter food supply for the population since there was not sufficient fodder to keep the beasts alive through the winter. No doubt the slaughter, with its sudden excess of food, was an occasion for [communal] feasting... [And] the ox-head was dedicated to the gods [expiatory: to regenerate them so that they would not 'run out' by human exploitation of them but would be able to continue to provide next year]... [But moreover] perhaps the magnificent head of the beast... was an awesome object containing heathen magic." (p. 46) That is, where anima-mana or energy was especially concentrated, and thus nutritious and capable of serving as a "mana pole" at the same time. "The association of magic with the head of an animal is a not uncommon feature of heathenism. The Celts hung the heads of sacrificial animals on trees... In the sixth century, [as an example of the Germanic animal-head ritual], the Lombards had a custom of singing and dancing around a goat’s head." The head of the animal species that was considered especially the materialization of the deity's anima could thus serve the same function as did the totem poles or idols. "In later Scandinavian tradition goats were [as mentioned] associated with Thunor/ Thor; they drew his chariot. In one account the flesh of Thor's goat was eaten but the bones and the skins were kept by the god, who revitalized them with his hammer." That is, the part given back to the god was to ensure the future supply of the animals, future re-materialization of the god as these sacred animals. "This myth may have led to the bones, including the skull, of the goat being considered sacred to the god" (p. 46 - 7).

The pagan (i.e. primitive) religion of the Germanic (Anglo-Saxon) peoples was practiced seasonally -- they marked macro-level time-units with seasonal feast and bonfire. In addition to the autumn feast of the oxen, we have mentioned that "[t]he winter festival which Bede called Mothers' Night marked the pagan New Year and was held on 25 December. It is likely that this Yule festival (the pagan name for December and January, we may remember, was giuli) involved the bringing in of evergreens, the burning of a Yule log and a feast centered round a boar's head." (p. 48) The "totem pole" this time was of the boar-anima, still associated sometimes with Freyr. "February, Bede tells us, was called Solmonath in heathen times, but 'it is possible to call Solmonath the month of cakes which, in it, they used to offer to their gods' (De Temporum Ratione, XV, Jones, p. 212)." (p. 49) The cakes were baked "in the images of the gods and in the shape of Freyr's boar (Grimm, Teutonic Mythology, I, p. 63 and note)." (Ibid.) The food for god was god itself, so made to look like god. So far Freyr's fertility seems the principal object of ritual "excitement". "Bede tells us that sacrifices were made [i.e. food was offered] to the goddess Hreda in March and that the festival of Eostre fell in April. At this time of year the associated rites would almost certainly be concerned with the celebration of spring... [and] bonfires were lit on hills during spring festivals." (Ibid.) Then the midsummer festival with bonfires "in the hills, but often in the streets", and the dance round or jump over the midsummer fire (seen also in Persia and Rome). (Ibid.) Herbs were also cast in it "to gain immunity from ill-health and misfortune", i.e. the endergonic "sacrifice" to appease or repair the dangerous spirits representing forces of linear entropy-increase. (Ibid.) Then September, Halegmonath (Holy month), with "feasting in celebration of the crop, as perpetuated by the Christian Harvest Festival. Probably the shadowy mythical figures of Sheaf and his son Beow (barley) were once associated with these rites." (Ibid.) Thus we have:

"From this brief survey of the pagan year, we can see that the people in general would have been closely involved in these festivals, raising crops and animals, baking cakes, collecting fuel for bonfires, flocking to see images or wagons carrying the gods and joining them in procession. Above all they feasted, enjoying the fruits of their own labour while propitiating the deities." (Undifferentiated communion-expiation; ibid.) Nancy Jay has mentioned the "relation between sacrifice and temporal continuity": "Ancient calendrical systems are chronological orderings of sacrificial festivals; examples are Greek, Israelite, Egyptian, Roman, Hawaiian, Ashanti, Chinese, Vedic, Aztec, and Mayan calendars. In ancient Greece, for example, [citing Burkert] 'the order of the calendar is largely identical with the sequence of festivals. For this reason the calendars exhibit an extreme particularism; there are virtually as many calendars as there are cities and tribes'." (Throughout Your Generations Forever, p. 151) The same phenomenon is evidenced here among the Anglo-Saxons. That festive-sacrificial religiousness organizes calendar or the division of time in general is the same as eating orders our daily division of time: a system, whether a social organism, the cosmos, or a biological organism, entropically runs down after a definite interval of time so as to require re-energization. Just as refill-hunger-refill (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) define the intervals of a unit of time ("day") repeated cyclically within the larger intervals ("season") of the macro-unit of time ("year", or one harvest cycle) repeated also cyclically -- and this is the primordial Zeitlichkeit corresponding to the sacred Weltlichkeit of the primitives -- so the communion feeding of society and the expiatory feeding of the god-cosmos have to take place seasonally within a year (i.e. defining the unit of time one level above daily, personal eating) to ensure the healthy functioning of both.

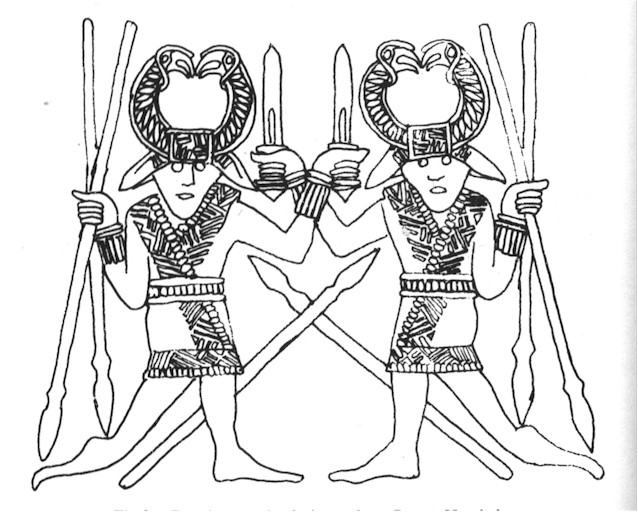

| "Dancing warriors" plaque from Sutton Hoo helmet, from Owen, p. 14. This picture gives us a notion of the custume of the Anglo-Saxon worriors around the 7th century A.D. |

The last ergonic sacrifice to be noted among the Germanic peoples is the endergonic deposit of energy in the (artificially constructed) structures of the cosmos to strengthen them. Just as among the late Neolithic and Bronze age Chinese here among the pagan Anglo-Saxons "we have a little evidence that an important occasion like the inauguration of a new building might involve sacrifice and the burial of the victim as a kind of 'guardian spirit': beneath the two posts which supported the roof of a hut in the Anglo-Saxon village of Sutton Courtenay... were placed the feet of a dog -- forefeet under one post, hind under the other. Under the entrance to King Edwin's hall at Yeavering rested the body of a man" (p. 48).

Just as among the Chinese Shang, among the pagan Germanic peoples both professional priests and "[k]ings and tribal chiefs figured in sacrificial and other pagan ceremonies" (p. 51), but "the populace were not allowed to share [in the mysteries] and to carry out any necessary sacrifices without fear of reprisal from offended parties" (p. 50). The king, whose "two main responsibilities [were] to keep his people fed and to ensure military victory" (p. 51), fulfilled the first by the seasonal sacrifices and feasts that catalyzed "the cyclic planting and harvesting of crops and the breeding and killing of beasts" (ibid.). "Warfare, less regular in its occurrence, was prefaced by divination." (Ibid.) The purpose of divination was to enquire the ancestral anima-mana about the future (energetic) state of the cosmos to which human enterprises were assimilated -- and the atmospheric Anima, running the cosmos, would of course know it. The king however could perform divination without the use of animals as vehicles of communication, and consequently not sacrifice on such occasion. Tacitus left a description of the method (Germania, 10; cited, p. 52):

| For auspices and the casting of lots they have the highest possible regard. Their procedure in casting lots is uniform. They break off a branch of a fruit-tree and slice it into strips; they distinguish these by certain runes [notis quibudam] and throw them, as random chances will have it, on to a white cloth. Then the priest of the state if the consultation is a public one, the father of the family if it is private, after a prayer to the gods and an intent gaze heavenward, picks up three, one at a time, and reads their meaning from the runes scored on them. If the lots forbid an enterprise, there can be no further consultation that day; if they allow it, further confirmation by auspices is required... (Owen, p. 52). | Auspicia sortesque ut qui maxime observant: sortium consuetudo simplex. Virgam frugiferae arbori decisam in surculos amputant eosque notis quibusdam discretos super candidam vestem temere ac fortuito spargunt. Mox, si publice consultetur, sacerdos civitatis, sin privatim, ipse pater familiae, precatus deos caelumque suspiciens ter singulos tollit, sublatos secundum impressam ante notam interpretatur. Si prohibuerunt, nulla de eadem re in eundem diem consultatio; sin permissum, auspiciorum adhuc fides exigitur. |

Compare this with the Shang or the general northern Asian procedure of burning animal bones (turtle shells, shoulder blades of an ox) and determining the response of the Ancestor by interpreting the cracks on them caused by the burning. Among the Germanic peoples there were also "sacrifices to establish contact with the spirit world" using principally the cock and the hen (Montgomery, ftnt. 59). We will see instances of this below.

4. Burial. The experience of the return of the breath-soul to the atmosphere after death gives rise to the belief of the journey of the soul to the world of the dead, where it needs to use just the same sort of things that it had needed to use when it was here among the living. Now the method of burials favored by the Saxons was inhumation (burial) while the Anglian preferred cremation (p. 68), in agreement with their self-designation of ancestry from Woden who had decreed cremation. In the case of inhumation the dead was always buried accompanied by things of daily necessities, the "grave goods"; which, if the dead had need of living beings when here, like servants or animals, would then constitute the second type of non-ergonic sacrifices, those for accompaniment: the killing of the living and the release of their souls to serve the dead in the afterlife. But the sacrifice of humans or animals was rare in burial as well as in cremation rites, reflecting more likely the material scarcity of Anglo-Saxon Britain that did not permit such waste of meat or labour. The inanimate equipment with which the Anglo-Saxon peoples accompanied their dead for their use in the afterlife were usually such things as spear in the case of dead men (possibly reflecting also the cult of Woden), and jewellery and spinning equipment in the case of dead women (p. 67). For both sexes there were also combs, pottery, and wooden containers, which probably held food or drink for the dead, thus serving the same function as sacrificial offering: feed for the soul. Even money was sometimes needed for the journey of the dead. The coins which have been found in the purse for the dead in Sutton Hoo ship burial (below) "were probably a symbolic payment for the forty oarsmen needed to row the ship" to the next world (p. 121; this practice "normally belongs with Greek and Roman paganism, where the common practice was to place a coin in the corpse's mouth. The custom had percolated into the Germanic world, apparently, since similar 'payments' occur in a small number of rich Frankish graves"; ibid.). "In some cases [of inhumation] superstitious practices may have been performed to prevent the dead person from troubling the living. These included decapitation of the corpse, the strewing of flints or placing of stones over the body and the burning of corn" (p. 73 - 4), but also the ritual breaking (killing) of spear and the filling of the grave soil with charcoal and pieces of pottery (p. 74). This again served the same function as did the defensive sacrifice (membrane formation): if the dead could not be placated with nutrients, then fortification had to be built to defend against them, or else they needed to be disabled or rendered weak and weaponless. The pagan graves were usually oriented north-south, but after conversion the Anglo-Saxon graves became east-west in the Christian manner (p. 74). "Surprisingly, it was in the seventh century, when Christianity was influencing people both physically and spiritually, that the Anglo-Saxons revived the custom of burial under barrows" (p. 75), which custom was general during the Bronze and Iron Age Britain. "Barrow burial plays a part in the northern mythology and in Icelandic literature is associated with Woden and with Freyr, who was himself believed to have been laid in a mound" (ibid.); but of course god could never "really" die. The purpose of the "raising of a burial mound" is "the ensuring of posthumous fame for the dead man." (p. 75) In this way, "[i]n what was probably the same urge to bury their dead under visible tumuli, certain sixth- and seventh-century inhabitants of England began using older barrows for their internment. Thus, mounds originally raised over Neolithic or Bronze Age graves came to be used, secondarily, by the Anglo-Saxons" (p. 78). The Christian Church stopped these pagan burial practices only by the end of the seventh century. Barrows (Old. Eng. hlaew) must not be thought of as some inheritance from the Proto-Indo-European ancestors, who were traditionally identified as the warrior nomads burying their chiefs in barrows in the southern Russian steppes some 4,000 B.C. (the "Kurgan culture" of Marija Gimbutas). As we shall see, the Proto-Indo-Europeans were most likely agriculturalists spreading out from Anatolia starting at least 6,000 B.C. (the view of Collin Renfrew and the recent Russian linguists). Furthermore, inhumation in mounds were motivated by the common experiences of ancient peoples and therefore was not peculiar to the Indo-Europeans (consider the gigantic burial mounds for the first emperor of China in Xian, 2,100 years ago).

Now before considering the cremation rites of the Anglo-Saxons, let us first look at the ship funeral rites peculiar to the sea-faring Germanic peoples. Here the dead was placed in a ship for his journey to the next world, "with the elaborate equipment the dead man would need for life [there] appropriate to his rank" (i.e. accompaniment; p. 97). The ship was then either towed out to sea and burnt, or burnt on land, or buried on land. Owen discusses three ship burials found in Britain, all in Suffolk, one at Snape (found 1862), two at Sutton Hoo (found 1938 & 1939). Ship burials originated in Scandinavia and spread outward from there such as to Britain. “In Scandinavia, where during the Iron Age, the dead were usually cremated and buried under mounds, a new type of ‘boat grave’ appeared in the sixth and seventh centuries. This new burial rite was complex: a boat was lowered into a large hole, the dead man was laid in it on a bed of grass accompanied by his weapons and domestic equipment; then a stallion and an old greyhound were laid beside the boat and killed. The boat was covered with planks, which included sledge-body side-rails, and covered with earth.” (Dolukhanov, cited by Montgomery.) The Anglo-Saxons followed this model. "It was evidently the practice of the community at Snape to cremate their dead and place the ashes in urns, in a common burial ground", with those for their leaders marked by a tumulus. (p. 102; more, below.) But the royal elite here received the special ship burial. The boat, 15m long and 3m wide, was brought along the River Alde to the nearest point to the cemetery, dragged uphill, placed in the trench already dug, with grave goods on its wooden floor, then buried unburnt. The first boat found at Sutton Hoo was 1.8m wide and 6.9m long, furnished with buckets holding food or liquor for the dead (the accompanying food). The second, 27.1m long and 4.3m across, lavishly furnished (the possible traces of animal sacrifice therein should be interpreted as "food to take with"), probably "commemorates Raedwald, King of East Anglia, who died in 624 or 625" (p. 107) and, although converted to Christianity, never abandoned paganism, having "in the same temple an altar for the holy Sacrifice of Christ side by side with an altar on which victims [food] were offered to devils [pagan gods and spirits]." (Bede, HE, cited by Owen, ibid.) This one was also dragged uphill and placed in the trench, with a large tumulus above.

Of ship cremated Ibn Fadlan again furnishes a description from the "Rus":

|

I was told that when their chieftains die, the least they do is to cremate them. I was very keen to verify this, when I learned of the death of one of their great men. They placed him in his grave (qabr) and erected a canopy over it for ten days, until they had finished making and sewing his [funeral garments].

In the case of a poor man they build a small boat, place him inside and burn it. In the case of a rich man, they gather together his possessions and divide them into three, one third for his family, one third to use for [his funeral] garments, and one third with which they purchase alcohol which they drink on the day when his slave-girl kills herself [or is sacrificed] and is cremated together with her master. (They are addicted to alcohol, which they drink night and day. Sometimes one of them dies with the cup still in his hand.) When their chieftain dies, his family ask his slave-girls and slave-boys, “Who among you will die with him?” and some of them reply, “I shall.” Having said this, it becomes incumbent upon the person and it is impossible ever to turn back. Should that person try to, he is not permitted to do so. It is usually slave-girls who make this offer. When that man whom I mentioned earlier died, they said to his slave-girls, “Who will die with him?” and one of them said, “I shall.” So they placed two slave-girls in charge of her to take care of her and accompany her wherever she went, even to the point of occasionally washing her feet with their own hands. They set about attending to the dead man, preparing his clothes for him and setting right all he needed. Every day the slave-girl would drink [alcohol] and would sing merrily and cheerfully. On the day when he and the slave-girl were to be burned I arrived at the river where his ship was. To my surprise I discovered that it had been beached and that four planks of birch (khadank) and other types of wood had been erected for it. Around them wood had been placed in such a way as to resemble scaffolding (anābīr). Then the ship was hauled and placed on top of this wood. They advanced, going to and fro [around the boat] uttering words which I did not understand, while he was still in his grave and had not been exhumed. Then they produced a couch and placed it on the ship, covering it with quilts [made of] Byzantine silk brocade and cushions [made of] Byzantine silk brocade. Then a crone arrived whom they called the “Angel of Death” and she spread on the couch the coverings we have mentioned. She is responsible for having his [garments] sewn up and putting him in order and it is she who kills the slave-girls. I myself saw her: a gloomy, corpulent woman, neither young nor old. When they came to his grave, they removed the soil from the wood and then removed the wood, exhuming him [still dressed] in the izār in which he had died. I could see that he had turned black because of the coldness of the ground. They had also placed alcohol, fruit and a pandora (tunbūr) [a musical instrument] beside him in the grave, all of which they took out. Surprisingly, he had not begun to stink and only his colour had deteriorated. They clothed him in trousers, leggings (rān), boots, a qurtaq, and a silk caftan with golden buttons [both ceremonial insignia to mark the deceased's honour], and placed a silk qalansuwwah [fringed] with sable on his head. They carried him inside the pavilion on the ship and laid him to rest on the quilt, propping him with cushions. Then they brought alcohol, fruit and herbs (rayhān) [M. mentions that these "were somehow used to effect communication with the spirit world"; hence not for use in the afterlife (as accompanying food and drug)?] and placed them beside him. Next they brought bread, meat and onions, which they cast in front of him, a dog, which they cut in two and which they threw onto the ship, and all of his weaponry, which they placed beside him. They then brought two mounts, made them gallop until they began to sweat, cut them up into pieces and threw the flesh onto the ship. [M. cites Smyser, “The sweating of the horses is evidently a relic of torturing sacrificial animals (or human beings) to enhance the value of the sacrifice to the god.” To, i.e., increase their energetic content. These, then, were all the non-ergonic sacrifices of accompaniment.] They next fetched two cows, which they also cut up into pieces and threw on board, and a cock and a hen, which they slaughtered and cast onto it. [The cock and hen do not here seem to be for communicational purpose, but for accompaniment, i.e. for equipment, food, or even divinational use in the afterlife. Thus M. cites Roesdahl (ftnt. 59): “These graves illustrate vividly concepts central to the traditional picture of Valhall. . . . What could be better to take to Valhall than your horse and weapons? Horses resplendent in their trappings were suitable for high-ranking men — even though they were not likely to have been used in battle — and presumably they also had to bear their masters to the Other World. Weapons were obviously necessary and the other grave-goods were no doubt useful both for the journey and for feasting on arrival.”] Meanwhile, the slave-girl who wished to be killed was coming and going, entering one pavilion after another. The owner of the pavilion would have intercourse with her and say to her, “Tell your master that I have done this purely out of love for you.” At the time of the evening prayer on Friday they brought the slave-girl to a thing that they had constructed, like a door-frame. She placed her feet on the hands of the men and was raised above that door-frame. She said something and they brought her down. Then they lifted her up a second time and she did what she had done the first time. They brought her down and then lifted her up a third time and she did what she had done on the first two occasions. They next handed her a hen. She cut off its head and threw it away. They took the hen and threw it on board the ship. [Evidently this was "a [shamanistic] way of communicating with the spirit world" by releasing the spirit of the hen which was to carry the slave-girl's soul to the yonder for a peek, as shown below.] I quizzed the interpreter about her actions and he said, “The first time they lifted her, she said, ‘Behold, I see my father and my mother.’ The second time she said, ‘Behold, I see all of my dead kindred, seated.’ The third time she said, ‘Behold, I see my master, seated in Paradise. Paradise is beautiful and verdant. He is accompanied by his men and his male-slaves. He summons me, so bring me to him.’” [M. cites (ftnt. 60) Simpson that "the wooden frame symbolizes a barrier between this world and the Otherworld" and notes further (ftnt. 61) that "[h]er dead master is apparently already seated at the communal table, feasting, before the cremation ceremony stipulated by Odin. She is, of course, under the influence of a strong hallucinogenic. Her desire to be reunited with family and her master contradicts Roesdahl’s assertion that 'apart from the Valkyries who fetched the dead warriors, there do not seem to have been any women in Valhall'".] So they brought her to the ship and she removed two bracelets that she was wearing, handing them to the woman called the “Angel of Death,” the one who was to kill her. She also removed two anklets that she was wearing, handing them to the two slave-girls who had waited upon her: they were the daughters of the crone known as the “Angel of Death.” Then they lifted her onto the ship but did not bring her into the pavilion. The men came with their shields and sticks and handed her a cup of alcohol over which she chanted and then drank. The interpreter said to me, “Thereby she bids her female companions farewell.” She was handed another cup, which she took and chanted for a long time, while the crone urged her to drink it and to enter the pavilion in which her master lay. [The nabidh was probably drugged, as M. notes (ftnt. 62).] I saw that she was befuddled and wanted to enter the pavilion but she had [only] put her head into the pavilion [while her body remained outside it]. The crone grabbed hold of her head and dragged her into the pavilion, entering it at the same time. The men began to bang their shields with the sticks so that her screams could not be heard and so terrify the other slave-girls, who would not, then, seek to die with their masters. [M. notes (ftnt. 64) Ibn Fadlān's possible failure "to see the ritual importance of the noise, intended to distract the attention of the spirit world, whose presence might mar the second ritual marriage inside the pavilion."] Six men entered the pavilion and all had intercourse with the slave-girl. They laid her down beside her master and two of them took hold of her feet, two her hands. The crone called the “Angel of Death” placed a rope around her neck in such a way that the ends crossed one another (mukhālafan) and handed it to two [of the men] to pull on it. She advanced with a broad-bladed dagger and began to thrust it in and out between her ribs, now here, now there, while the two men throttled her with the rope until she died. Then the deceased’s next of kin approached and took hold of a piece of wood and set fire to it. He walked backwards, with the back of his neck to the ship, his face to the people, with the lighted piece of wood in one hand and the other hand on his anus, being completely naked. He ignited the wood that had been set up under the ship after they had placed the slave-girl whom they had killed beside her master. Then the people came forward with sticks and firewood. Each one carried a stick the end of which he had set fire to and which he threw on top of the wood. The wood caught fire, and then the ship, the pavilion, the man, the slave-girl and all it contained. A dreadful wind arose and the flames leapt higher and blazed fiercely. One of the Rusiyyah stood beside me and I heard him speaking to my interpreter. I quizzed him about what he had said, and he replied, “He said, ‘You Arabs are a foolish lot!’” So I said, “Why is that?” and he replied, “Because you purposely take those who are dearest to you and whom you hold in highest esteem and throw them under the earth, where they are eaten by the earth, by vermin and by worms, whereas we burn them in the fire there and then, so that they enter Paradise immediately.” Then he laughed loud and long. I quizzed him about that [i.e., the entry into Paradise] and he said, “Because of the love which my Lord feels for him. He has sent the wind to take him away within an hour.” Actually, it took scarcely an hour for the ship, the firewood, the slave-girl and her master to be burnt to a fine ash. They built something like a round hillock over the ship, which they had pulled out of the water, and placed in the middle of it a large piece of birch (khadank) on which they wrote the name of the man and the name of the King of the Rūs. Then they left. (Montgomery's translation, ibid.; Owen's translation, ibid., p. 98 - 101.) |

As Foote and Wilson have noted (cited by Montgomery), "striking elements in this description [by an Arab of a people mixed between Germanic and Slavic], such as the ‘Angel of Death,’ the ritual intercourse, and the wary and naked kindler of the pyre, cannot be paralleled in Norse sources". The statement “Because of the love which my Lord feels for him. He has sent the wind to take him away within an hour” is quite instructive in confirming the original experience of divinity to be the atmosphere, wind, or air, to which the breath-soul is assimilated after its departure from the body. The dead is seen returning to the atmosphere when the atmospheric Anima violently swoops him up. Remember that the sacrificial food for the god is preferably burnt and rendered smoke so as to be congruent with the ancestral spirit, i.e. to easily blend into the atmosphere, thus being "eaten" by the Anima. As Montgomery writes in footnote (68) at this juncture: "Compare this with Snorri Sturluson’s comments: 'Odin made it a law that all dead men should be burnt, and their belongings laid with them on the pyre, and the ashes cast into the sea or buried in the ground. He said that in this way every man would come to Valhalla with whatever riches had been laid with him on the pyre... Outstanding men should have a mound raised to their memory, and all others famous for manly deeds should have a memorial stone... It was their belief that the higher the smoke rose in the air, the higher would be raised the man whose pyre it was, and the more goods were burnt with him, the richer he would be.' (Simpson, 193)"

Snorri Sturluson's recollection of Odin's decree captures the original motivating experience behind cremation. Owen notes that "those who cremated seem to have had a rather different conception of the afterlife from those who inhumed... [They] believed that fire worked some metamorphosis." (p. 79) In Beowulf the description of the cremation of the hero on the pyre itself is finished, after the mournful song of the Geatish woman, with the statement "Heaven swallowed the smoke." (p. 85) The poet also describes the cremation of another hero, Hnaef: "Heads melted, gashes sprang open, then blood flowed out of the body's wound. Flame, greediest of spirits, swallowed up all of those whom the battle took there, from both nations." (p. 86) It is not a different conception that is at issue, but a more forceful expression of animism: cremation, as a means of "melting" the body into the atmosphere, is the most forceful way to separate the breath-soul from the body and return it to the atmosphere (p. 20). In the daily circumstances of the Anglo-Saxons, however, "rather than being laid upon a pyre as in the literary tradition, the corpses were normally laid on the ground, or in a shallow trench, and the pyre heaped over them." (p. 87) The whole thing was also done haphazardly. Animals (pigs, oxen, horses, according to the age, sex and rank of the deceased) may have been burnt with the dead as food -- or for clothing and labour -- in the next world. The remains, as already hinted, were placed in pottery vessels and buried in the ground ("and some cremated remains were buried in the ground without vessels", p. 88). The ash constituted the "material" waste left behind after the "spirit" was rendered back to the atmosphere ("...the release of the spirit by fire which cremation was supposed to achieve", p. 88). But many of the pottery vessels had a hole in them to perhaps allow the soul of the cremated person to go in and out.

Of the varieties of decorational patterns on the burial potteries, the most interesting was the "wyrm motif", which "owed its popularity in the first place to its ritual significance as a protective device." (p. 90) Apparently, animae feared as forces of entropic disintegration could also be positively employed.

Of the varieties of decorational patterns on the burial potteries, the most interesting was the "wyrm motif", which "owed its popularity in the first place to its ritual significance as a protective device." (p. 90) Apparently, animae feared as forces of entropic disintegration could also be positively employed.

5. Mana objects. If shaman is the personnel intermediate between the world of the living flesh and the world of the spiritual dead, "mana-objects" are the instrumental intermediate. The Anglo-Saxon manifestations of these have been unearthed from Sutton Hoo: the whetstone sceptre (figure below), "an object of magic and potency, whether in enlisting the aid of ancestors or warding off evil" (cited by Owen, p. 113), i.e. like a mini-portable mana pole, a concentrator, conductor, or reincarnation point of the ancestral anima-mana of the atmosphere. First of all, the stag standing "on top of the sceptre, seems to have been a symbol of royalty in the northern world" (p. 114); secondly, the anima-mana in question seems to be that of Odin, the conceived ancestor of the royal house. "[T]hose special powers and influences that established the fortunes of the Sutton Hoo royal house were encapsulated in the staff, as Odin's divine strength was in his spear." (Cited by Owen, p. 114) Similar in function to the sceptre is the standard (see figure).

| <- The whetstone or sceptre from Sutton Hoo

The standard from Sutton Hoo -> |

|

6. A brief remark on the conversion and afterwards A major break in the otherwise natural course of the evolution of consciousness of the Germanic people occurred in the transitional period between pre-invasion and post-invasion, as a result of their Christianization. The civilizing forces from the Mediterranean region quickly broke down this paganism. We can only surmise that if the Germanic peoples had been left alone to develop into kingdoms in an “interaction sphere” of their own – that is, the emergence of mutually competing centralized states from mutually competing tribes or tribal confederates – there might emerge from some units of them, as did in other native spheres of civilization, grand philosophers pronouncing grand systems of the cosmos or spiritual enlightenment or great prophets ushering in some universal religions. But the fact is that they were caught up in the affairs of Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations. First some of them were “Christianized” in Arianism, e.g. the Franks. As the Franks established the first “state” the Germanic peoples knew, the forces of Catholicism took root there. This is the beginning of the Germanic peoples entering a new stage in their ideological mode. J. M. Wallace-Hadrill’s The Frankish Church offers a good account of the second stage, Catholicism, superceding the primitive animistic beliefs of the pagan Germans. The turning point is of course the conversion of Clovis. After his conversion, he ordered his Frankish noble followings to do the same, i.e. to be baptized. Thus the upper crust, and the upper crust only, of the Frankish peoples were now truly Catholic Christians, abandoning the last traces of loyalty to the primitive gods. This is the most important moment, setting up the course of the “Western civilization” that was to spring from Frankish descendants. At the moment, however, the “event” seemed almost a pure political expedient: through his new belief the king had now gained the active collaboration of the Gallo-Roman bishops, and so had the administrative controls over the Gallo-Romans who really ran Gaul. He also had now all the support from both the Roman church and the Eastern Empire in conducting the expansion of his kingdom. The king began granting charter to new churches all over the Frankish territory, ensuring a Christian life for the coming continental European civilization.

Across the English channel the Anglo-Saxons too were converted to Catholicism from their tribal pagan beliefs, with the coming of Augustine in the last years of the sixth century A. D. The process is narrated in detail in the last two chapters of Owen’s Rites and Religions. One cannot help but notice the neat coincidence: the move into the next level of political organization (from tribes to the beginning forms of “state”) was accompanied by the move into the next level of ideological belief (from shamanistic belief to an universal, salvational religion). If the political advance was “native” or only moderately influenced by the Romans, the ideological advance was entirely “Roman-induced”. This is the “break” in mental evolution that we meant earlier.

What follows in the history of the mind of the Germanic (now Western) peoples is the history of Catholicism. Jaroslave Pelikan’s The Growth of Medieval Theology (volume three of his The Christian Tradition) covers this portion of the story; it provides an overview of the entire history of Catholicism up to the point of Reformation. Now that the Frankish and Anglo-Saxon kingdoms were firmly connected with the Roman past in ideological history, a single Catholic tradition can be talked about as the overarching Latin Christendom encompassing the new Germanic players and the old Roman veterans; and this Catholic tradition, Pelikan shows, was consolidated around the teachings of St. Augustine in the early Middle Ages. The next thousand years of the Catholic tradition were to be Augustinian, either reactions against St. Augustine or re-affirmation of St. Augustine. First there was the consolidation of the Augustinian synthesis. From the end of the 8th century to the end of the 9th there appeared among the theologians the tendency to question this synthesis. Then followed the rather uneventful 10th and 11th century when theological speculation focused much on Christ and salvation through him. Then the 12th century was noted for the beginning of the cult of Virgin Mary as the mother of God. Then came controversies over the question of faith as a result of the theological “awakening” in the past centuries. The next, thirteenth century seems in one aspect to be of immense importance for the Catholic tradition, dominated by key figures such as Pope Innocent III, Saint Dominic, Saint Francis of Assisi, Thomas Aquinas, etc., but in terms of Christian “doctrines” (i.e. the official teachings of the church) this period was actually one of relative peace, the period of synthesis of all the thoughts previously achieved.

A most visible manifestation of the Christian intolerance often cited is the Inquisition, which is the subject of Bernard Hamilton’s The Medieval Inquisition. His main thesis is, however, that contrary to modern people’s perception of the Medieval Inquisition as an horrendous oppressive mechanism that involved torture of innocent people, in reality it was a rather moderate oppression (especially in comparison with the later Roman and Spanish Inquisition) that had as its principal aim the conversion of specifically Catharism and which only rarely involved imprisonment or death penalty. Catharism was a sort of dualism (on the Egyptian Gnostic model) which descended from the Bogomils in Bulgaria in the tenth century, and which became prominent in southern France in eleventh century or so. The Medieval Inquisition was founded principally to stamp out Catharism, but from the beginning lack of coordination and centralization weakened its effectiveness. The inquisitors hired were principally the mendicant orders – Dominicans and Franciscans – and a certain leniency and rationality characterized their work: always offering a grace period before starting the inquisition and always more concerned with conversion than punishment and therefore willing to forgive; and above all, they were cautious in conducting the trial, always vigilant of simple revenge being the true motive of the accusers. Furthermore, since “punishment” of the heretics was the business of the church and not of lay authority, it was technically called “penance,” and usually involved pilgrimage, and only rarely imprisonment or death. The author, however, points out that the use of prison as a standard form of punishment in later times must have its conceptual origin in the time of Inquisition.

The raw material of the Western civilization is produced by the "Germanic invasions." The most peculiar aspect of the "Western civilization" that emerged from these is the infusion of foreign material to produce it – in contrast with the Chinese, Mesopotamian, Egyptian, or Meso-American civilization which sprang spontaneously from its native soil without outside stimulus. If the Germanic tribes had not been caught up in the politics of the Roman empire, and if they had not been colonized on their mental plane by the Roman (Christian) religion, then the civilization that may have sprung from their soil would have taken a different shape – perhaps not very different in political form, but certainly extremely different in ideological (i.e. religious) outlook, considering that many scholars have traced the origin of some major social and political phenomena of the modern European theatre, including nationalism, communism, and Nazism -- and we have added feminism -- to Christianity. How would the "Germanic religion", a typical "intraworld" religion, differentiate later on? Into the first mode? The second mode (i.e. philosophy)? Or perhaps the Germanic and Celtic Europe might simply have remained tribal, and its religions intraworld, like New Guinea or Australia.

Footnote:

1. As for who these people called the "Rus" were, Montgomery favors their identification as "a people in the process of ethnic, social and cultural adaptation and assimilation — the process whereby the Scandinavian Rūs became the Slavic Rus’, having been exposed to the influence of the Volga Bulghars and the Khazars"; As he cites Logan: "In 839 the Rus were Swedes; in 1043 the Rus were Slavs. Sometime between 839 and 1043 two changes took place: one was the absorption of the Swedish Rus into the Slavic people among whom they settled, and the second was the extension of the term ‘Rus’ to apply to these Slavic peoples by whom the Swedes were absorbed."

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |