|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One

Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial

2.B.1. A Genealogy of the Philosophic Enlightenment in Classical Greece

Chapter 14: The Theory of Forms and the Story of the Good in Plato's Republic

ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY

|

Copyright © 2004, 2005, 2006 by Lawrence C. Chin. This chapter is best viewed in Google Chrome of Internet Explorer. In Safari or Firefox, the Greek characters will not show.

The "theory" of forms together with the Agathon is meant to explain the structure and source of existence through the comprehension (rather, the anamnesis) of which (major) salvation is possible. It -- and so the exposition of salvation -- is completed only in the Republic, of which it forms the emanating kernel. But it must be noted that in theme the Republic has shifted from the major salvation of Phaedo to minor salvation, i.e. the order of the soul and of the human social collective (polis): justice. The kernel really comprises three "stories": the story of the Good; the story of the divided line; and the story (allegory) of the cave. Here we deal with the story of the Good (the Agathon).1

(1) In Book V of the Republic important distinctions are made between (a) the ordinary person engaged in everyday concern (the pre-ontological, in Heidegger's words, or of the "work-a-day" mode) and the philosopher; (b) knowledge (episteme) and opinion (doxa); and (c) what is and what is and is not at the same time, which is also a distinction between the one and the many, and between "two modes of showing", showing as one and as many. The following exposition of this most difficult part of Platonic dialogues will make extensive use of John Sallis' Being and Logos.

The "theory of the form" is fully elaborated here, after which the Good is explicated as much as possible. The forms -- formally understood as necessary hypothesis -- appear in our linguistic description of reality, i.e. in the conceptualization of reality through logos; that is, through our speaking about reality on the level of things an underlying layer of forms emerges as conditional for the intelligibility of things (for their making sense as they are, as this and that thing), in the same manner as (the analogy to be used later) langue is underlying and conditional for parole. There is, in Sallis' words, a definite "connection between logos and the process of [things'] becoming manifest [as such as they are, this chair here, that house there]." (Sallis, ibid., p. 13)2

"In posing [the question, What is logos?] we have in mind the double meaning of the verbal form 'legein', which means both to say, to speak, and to lay in the sense of bringing things to lie together, collecting them, gathering them together; and we have in mind the question posed by this double meaning, namely, the question as to how it is that saying (and, in general... language) could have presented itself to the Greeks as a laying, a gathering together. We have in mind a primordial 'experience' of language as 'gathering lay'..." (Ibid., p. 7. C.f. The comparison between the Dao of Laozi and the logos of Heraclitus and John.)

In speaking, in addressing this as beautiful and that also as beautiful, we notice that the many beautiful things would not be beautiful unless underlying them is, or unless we understand beforehand, the concept "beautiful" with reference to which the beautiful things can be understood as beautiful, and which furthermore, in contrast with those many things referring to (partaking of) it in order to be so understood, is invariably one. (We are going into distinction c here.) Moreover when addressing this as beautiful we are saying that it is not ugly. epeidh estin enantion kalon aiscrwi, duo autw einai. "Since the beautiful is the opposite to ugly, they are two." Two forms are showing up in such addressing. oukoun epeidh duo, kai en ekateron. "Since they are two, isn't each also one?" (476)

Forms are (each) one -- this is the essential nature of this underlying, conditional layer of reality. But in their manifestation -- showing forth -- in the (empirical, temporal) world, i.e. always in things thus addressed in speech, they show up as many, as this and that beautiful thing: a form only shows up through embodiment -- the eternal and unvarying only showing up to us through temporalization, within the thermodynamic flux. Kai peri dh dikaiou kai adikou kai agaqou kai kakou kai tautwn twn eidwn peri o autoV logoV, auto men en ekaston einai, thi de twn praxewn kai somatwn kai allhlwn koinwniai pantacou fantazomena polla fanesqai ekaston. (476 - 5) "And the same logos holds for justice and injustice and good and bad and all the other forms; each is itself one, but [by showing up] in communion with actions, bodies [i.e. the thermodynamic flux], and one another does it appear to be apparitional many."

(a) The distinction between the ordinary person and the philosopher. The ordinary person, here characterized with regard to their comportment toward beauty, comport themselves solely toward beautiful things. oi men pou... filhkoi kai filoqeamoneV taV te kalaV fwnaV aspazontai kai croaV kai schmata kai panta ta ek twn toioutwn dhmiourgoumena, autou de tou kalou adunatoV autwn h dianoia thn fusin idein te kai aspasasqai. (476 b 5) "On the other hand, the lovers of hearing and lovers of sight... surely delight in [lit. greet] beautiful sounds and colors and shapes and all that crafted from these, but their thought [dianoia] is unable to see and delight in [greet] the nature [phusin] of the beautiful itself."

As for the philosopher: oi de dh ep'auto to kalon dunatoi ienai te kai oran kaq'auto ara ou spanioi an eien; "... wouldn't those able to approach [go to] the beautiful itself and see it according to itself be rare?" (476 b 10)

The ordinary person is dreaming. O oun kala men pragmata nomizwn, auto de kalloV mhte nomizwn mhte, an tiV hghtai epi thn gnwsin autou, dunamenoV epesqai, onar h upar dokei soi zhn; skopei de. to oneirwttein ara ou tode estin, eante en upnwi tiV eant'egrhgorwV to omoion twi mh omoion all'auto hghtai einai wi eoiken; "Is the [person] holding [that there are] beautiful things but not holding [that there is] the beautiful itself nor, if some one leads [him] to the knowledge [gnosis] of it, being able to follow [the guide] -- does [this person] seem to you to live in dream or awake? Look at it this way. Isn't dreaming precisely this, that whether in dream or awake, someone believes the likeness of something to be not likeness but rather that itself to which it is like?" (476 c2)

The philosopher is awake. o tanantia toutwn hgoumenoV te ti auto kalon kai dunamenoV kaqoran kai auto kai ta ekeinou meteconta, kai oute ta meteconta auto oute auto ta meteconta hgoumenoV, upar h onar au kai outoV dokei soi zhn; "The [person] -- contrary to these -- believing [there is] the beautiful itself and able to see it itself and those partaking of it, and not believing those partaking [of it] to be it itself nor it itself to be those partaking [of it], does this [person] seem to you to live in dream or awake?" (476 d)

There are thus four logically possible types of person:

- who sees forms only (what is): actually impossible, non-existing type.

- who sees both forms and things partaking of them (what is & what is and is not; see below): philosophers.

- who sees only things (what is and is not): ordinary person.

- who sees nothing (what is not): actually impossible, non-existing.

(b) The distinction between knowledge (episteme, gnosis) and opinion (doxa). oukoun toutou men thn dianoian wV gignwskontoV gnwmhn an orqwV faimen einai, tou de doxan wV doxazontoV; "And it would be right if we say that the thought [dianoia] of this [person: the philosopher], insofar as he knows, is knowledge [gnomen], and of the [other person: the ordinary person], opinion [doxa], insofar as he opines?" (476 d 5)

(c) The distinction between the one and the many, what is and what is and is not, the "two modes of showing". Socrates asks, o gignwskwn gignwskei ti h ouden; "Does the knowing [person] know something or nothing?" ti. "Something." (476 e7) poteron on h ouk on; "Is [this something] being or not-being?" (476 e 10) On. PwV gar an mh on ge ti gnwsqeih;. "Being. For how can non-being be something known?" This answer of Glaucon to Socrates echoes the goddess' introduction to Parmenides as a young man.

Plato:

- what is (being), entirely knowable: to men pantelwV on pantelwV gnwston, "the entirely being [is] entirely knowable" (477 3), corresponding to knowledge (gnosis, episteme): Oukoun episthmh men epi twi onti pefuke, gnwnai wV esti to on; "And isn't knowledge by nature [tended] toward being, to know how being is?"

- what is and is not, opinable. ei de dh ti outwV ecei wV einai te kai mh einai, ou metaxu an keoito tou eilikrinwV ontoV kai tou au mhdamhi ontoV; "If now there is something such as both to be and not to be, wouldn't it lie between the purely being and the in-no-way being?" (477 a 5) This, of course, corresponds to opinion (doxa).

- what is not, non-being, entirely and in no way knowable: mh on de mhdamhi panthi agnwston (477 3). Corresponding to ignorance (agnoia).

Socrates is making a strict distinction between doxa and episteme (a more technical designation of gnosis). For this he has to define power precisely. Fhsomen dunameiV einai genoV ti twn ontwn, aiV dh kai hmeiV dunameqa a dunameqa kai allo pan oti per an dunhtai, oion legw oyin kai akohn twn dunamewn einai, ei ara manqaneiV o boulomai legein to eidoV. (477 c) "We say that power is a certain kind [genos] of beings by which we are capable of what we are capable of and also everything else is capable of whatever it is capable of, as when I say sight and hearing are among powers, if perchance you understand the form of which I wish to speak." dunamewV gar egw oute tina croan orw oute schma oute ti twn toioutwn oion kai allwn pollwn, proV a apoblepwn enia diorizomai par'emautwi ta men alla einai, ta de alla. dunamewV d'eiV ekeino monon blepwn ef'wi te esti kai o apergazetai, kai tauthi ekasthn autwn dunamin ekalesa, kai thn men epi twi autwi tetagmenhn kai to auto apergazomenhn thn authn kalw, thn de epi eterwi kai eteron apergazomenhn allhn. "For by power I see not some color nor shape nor anything of the sort such as in many other things to which I look when I distinguish individual things for myself, that these are these, those are those. By power I only look to this, on that which it is [i.e. depends] and that which it accomplishes. And by this I called each [power] of these a power, and that which depends on the same thing and which accomplishes the same, I call the same [power]; and that which depends on another and accomplishes another I call another [i.e. different power]." (477 d) In this sense the power specific to knowing or knowledge (episteme) is the most "vigorous" of all powers (paswn dunamenwn errwmenestathn, 477 d-10). Opining -- that power by which we can opine (wi doxazein dunameqa) -- is a different power, weaker, capable of mistakes (anamarthton) in contrast to "knowing" (the power for episteme) which is not capable of mistakes (mh anamarthton). The two, by their different natures, are dependent on or proper to different matters (ef'eterwi ara eteron ti dunamenh ekatera autwn pefuken), one on being (forms and their showing as forms -- and ultimately, the form of the Good showing in these forms' showing themselves) and knowing being and how being is (episthmh men ge pou epi twi onti, to on gnwnai wV ecei), the other, opinion, opining neither-being-nor-non-being (ouk ara on oude mh on doxazei; 478 c6). Opinion is therefore in-between, darker than knowledge and brighter than ignorance (gnwsewV men soi fainetai doxa skotwdesteron, agnoiaV de fanoteron).

At this point two important issues arise. First, Socrates is elaborating on the two ways as introduced by the goddess in Parmenides' vision (ei d'ag'egwn erew, komisai de su muqon akousaV, aiper odoi mounai dizhsioV eisi nohsai. [So the goddess says to Parmenides the young man in his vision:] "Come and I'll say, and you, having heard, take [with you] the story, what are the only paths of search for thinking..." [Frag. 2]):

- h men opwV estin te kai wV ouk estin mh einai, peiqouV esti keleuqoV, alhqeihi gar ophdei "The one way, that Is and that it is impossible for it [Is] not to be, this is the road of persuasion, for it follows truth."

- h de wV ouk estin te kai wV crewn estin mh einai, thn de toi frazw panapeuqea emmen atarpon. oute gar an gnoihV to ge mh eon, ou gar anuston, oute frasaiV "The other way, that Not Is and that it is necessary that it [Not-Is] should not be, this way I show you to be a path of total unknown, for you cannot know Non-Being nor articulate [phrase] it, for it [Non-Being] is not possible."

Parmenides' two paths therefore are taken up into Plato's two extremes. The goddess then reveals to Parmenides the young man the third, the "opinion of the mortals" (doxa broteiaV), the empirical world, "the deceptive cosmos" (kosmon apathlon; Conche's translation: "le trompeur arrangement-en-monde"), which then is taken up into Plato's in-between, both-being-and-non-being or neither-being-nor-non-being or... deceitful in this way.

Second, the meaning of that "neither-being-nor-non-being", which is going to figure, on the other side of Eurasia, so prominently in Buddhist discourses on the nature of this world. There are three senses of this.

The first is that of the traditional metaphysics: beings are the presence and absence of Being. "[The ontological tradition] tries to think [Being and beings] together, but not as if To-be were just another though greater being which somehow produces all other beings as different from itself [as imagined by the first mode of the testamental religions]. Rather, beings are, and they are not 'other' than their process of Are-ing; for other than To-be [the entirely being] 'is' only Not-to-be [the in-no-way being]... [But] Be in its fullness [i.e. 'entirety'] is 'absent' from and in beings... beings come-to-pass only as Be presences but not-all-at-once [in between the two extremes]." (D. Guerrière, c.f. "The Traditional Metaphysical Reading of Parmenides"). There, in accordance with the general orientation of this work, this meaning of beings as both (or neither) to be and (or nor) not to be is rejected as illogical.

The second sense is that of the thermodynamic reading of Buddhism, where Socrates' formula corresponds to, e.g. Chi-Tsang's second level of truth concerning the truth of existence (of beings): "things neither exist nor do not exist." (萬物非有非無) The third level might as well be brought in: "things neither exist nor do not exist, but not that they not exist nor that they not not-exist; the middle path is not one-sided, but neither is it not one-sided." (萬物非有非無, 而又非非有非非無,

中道不片面, 而又非不片面. C.f. "The Conception of Non-Being in Chinese Philosophy".) Or in Buddha's original words regarding the person that has reached Nibbana and for whom the chain of origination and the wheel of death and rebirth -- i.e. the empirical cosmos -- has dissolved as just so much illusion -- which it really is -- his "ego" or individuality is thus to be spoken of: "And if anyone were to say to a monk whose mind was thus freed: 'The Tathagata [i.e. enlightened one] exists after death', that would be a wrong opinion and unfitting, likewise: 'The Tathagata does not exist..., both exists and does not exist..., neither exists nor does not exist after death.'" (Sutta 15 in Digha Nikaya, trans. by Maurice Walshe.) This is the sense in which the empirical, visible reality around us (beings) is virtual, existing but not really existing, and this virtual existence is in fact the only logically possible existence given the law of Conservation. It is because of this that the first sense is rejected, since even the slightest self-withholding of Being is illogical. This is also the sense in which modern cosmology converges with the Sunyavada and Chinese Buddhism. (Later.) But this sense seems only implicit elsewhere in Socrates' speech (below on the Good) and not the sense here.

What does seem to be Socrates' sense here is the third sense provided by John Sallis. The world of beings is that which appears, manifests as being and non-being at the same time (ei ti faneih oion ama on te kai mh on..., 478 d 5). This third sense relates to the "second mode of showing". If the distinction between "what it is" and "that it is" -- the foundation for the later distinction between existence and essence -- be recognized as being implicitly made by Socrates here (as he does make it, below), then the second sense relates to "that it is" and this third to "what it is", "how it shows itself". This sense is also logically correct, for now, i.e. in this functional perspective. Hence we retain the second and third sense, rejecting the first.

The cause of this ambiguity of beings (in both the second and third sense) is, of course, their embodiment, i.e. in the temporal, thermodynamic flux. The characterization as virtual reality and as ambiguous showing-forth is also in terms of participating in or partaking of both to-be and not-to-be (to amfoterwn metecon tou einai te kai mh einai; 478 e). Now in the noticing, in the emergence of the conditions (forms) for things' appearing as they are, say, as beautiful (manifestness, unconcealedness), in logos, in our linguistic description of reality, a certain problem becomes also evident, the third sense as ambiguous showing-forth. Thus Socrates asks: Toutwn gar dh... fhsomen, twn pollwn kalwn mwn ti estin o ouk aiscron fanhsetai; kai twn dikaiwn, o ouk adikon; kai twn osiwn, o ouk anosion; (479 5) "Now, of these many beautiful things... we'll say, is there any that won't appear also as ugly? And of the just things, also any that won't appear as unjust? And of the holy, also any that won't appear as unholy?" As Glaucon answers: Ouk, all'anagkh... kai kala pwV auta kai aiscra fanhnai, kai osa alla erwtaV. "No, but it's necessary that they appear as beautiful and also as ugly, and so on with all the others you ask about." Socrates continues: Kai megala dh kai smikra kai koufa kai barea mh ti mallon a an fhsomen, tauta prosrhqhsetai h tanantia; (479 6) "And those things we say to be big and small and light and heavy, are they to be addressed as such [by such name] any more than as the opposite [by the opposite names]?" We know Glaucon's answer. So Sallis explains: "It should be carefully noted that Socrates began by speaking about how things look (e.g. beautiful things also look [rather "appear", phanetai] ugly). But then he made a transition -- an extremely crucial transition -- from how things look to how they are addressed by name, from looking to being-named." (Ibid., p. 391) So in the end, Glaucon admits: kai gar tauta epamfoterizein, kai out'einai oute mh einai ouden autwn dunaton pagwV nohsai, oute amfotera oute oudeteron. (479 c) "For the many are ambiguous, and it's not possible to think of them fixedly as either being or not-being, or as both or neither." This then corresponds to Chi-Tsang's third level of truth (the Middle Path), except that, as said, Plato is interested in the many's showing and not (yet) in their existence as such, as with the Buddhist. "Note carefully what Glaucon is concluding... that these things cannot be thought fixedly, determinately, at all." (Sallis, ibid., p. 392) This is valid of both the second and the third sense: both their existence as such and their existence as this or that cannot be thought determinately. But Sallis quickly switches to the third sense of showing. "What is encountered by the attempt to think them is something indeterminately manifold, an indeterminate many..." (Ibid.)

"The crucial question which we need to consider in reference to this discussion is: precisely how does it happen that these things come to be manifested as indeterminate manys? In other words, how is the transition made from that stage at which things look both beautiful and ugly to that stage at which they present themselves as indeterminate manys, i.e. as neither beautiful nor ugly nor both nor neither?... the answer: the transition is a transition from looking to being-named." That is, just as the underlying reality of forms conditioning the surface, empirical reality of things becomes manifest in logos, so does the (indeterminate) nature of this surface reality, otherwise un-noticed. "But how is it that calling the things by name is able to bring about such a transition? Initially the thing looks both beautiful and ugly. Such 'looking' ['appearing'] is possible only if the beautiful and the ugly have not been explicitly distinguished. This is evident if one considers what happens once the beautiful and the ugly are distinguished, that is, once they are posed as distinct, as opposed, as mutually exclusive. [This is forms appearing in speech.] What happens is that when the thing looks beautiful, this looking carries with it the exclusion of the ugly, so that to look beautiful is to look not ugly. But, in turn, the thing also looks ugly, and its looking ugly excludes the beautiful from its looks. The result is that the thing cannot be fixed, i.e. determined, (1) as beautiful, since it looks ugly, nor (2) as ugly, since it looks beautiful, nor (3) as both, since the beautiful and the ugly exclude one another, nor (4) as neither, since it looks ugly and beautiful. Withdrawing from all of these determinations, proving not to be determined by them, the thing thus presents itself as indeterminate many. Hence, the relevant transition is made and the thing becomes manifest as indeterminate many only when the distinction between the beautiful and the ugly is posed [i.e. when the forms appear]. But how does this distinction get posed? What does this posing involve? It is merely a posing (in proper distinctness) of what is named in the names. That is, it is a posing of that as which the thing is addressed when it is addressed by the names 'beautiful' and 'ugly' -- a posing of each as one in distinction from and opposition to the other. [The posing is the moment of the appearance of forms, which appear always definitely and as one, not many.] Therefore, what primarily makes the transition possible is a posing of an order of distinctness by means of names. More precisely, what makes the transition possible is an addressing of the things by name in which there is simultaneously a posing of what is named in the name [i.e. the form], a posing of it over against the things, as 'hypothesis'."

"We need to relate this very crucial discussion of the indeterminate many (as between being and non-being) to the fundamental distinction introduced earlier between what an eidos is (or alternatively, a showing in which it would show itself as it is) and a showing in which it shows itself in community with actions, bodies, and other eide and thus shows itself as it is not, as many. Clearly, what is between being and non-being (indeterminate manys) corresponds to the latter, to the second mode of showing: such a thing comes forth in a showing in which an eidos shows itself in community with other things so as to look like many -- for example, in a showing in which the beautiful shows itself, not as it itself is (as the same as itself, as one) but rather as also ugly, as passing into ugly, as mixed with ugly. So, that showing in which an indeterminate many stands forth is a showing in which something (which is itself) shows itself as it is not. It is in this connection [but this is only the third sense] that we must understand what is meant in saying that such things are between being and non-being. On the other hand, what stands forth in such a showing is distinguished from being by the negativity which belongs to the showing, the negativity consisting in the fact that what shows itself shows itself as it itself is not. On the other hand, it is distinguished from non-being by a corresponding positivity, a positivity which consists in the fact that, in such a showing, something shows itself; that is, even if it shows itself as (i.e. so as to look like) what it is not, even if it shows itself in disguise, even if it shows itself in such a way as also to conceal itself, nevertheless, it does show itself, it is not totally concealed..."

"[This] indicates that the difference between the knowable and the opinable is just the difference between the two modes of showing. This means, in turn, that the distinction between the knowable and the opinable is not fundamentally a distinction between two kinds of things, between which some relation would subsist, but rather a distinction between two ways in which an eidos can show itself. It is a distinction between a showing in which an eidos shows itself as it itself is (as one [and by itself]) and a showing in which an eidos shows itself as it is not (as many [and in things, i.e. in community with other eide]). In both cases what shows itself is the same thing (the eidos) -- which is to say that the knowable and the opinable are not two parallel regions of things. A beautiful thing is just that which stands forth in a showing in which the beautiful itself shows itself as it is not (i.e. in the second mode of showing); this -- and only this! -- is the proper sense in which a beautiful thing is an image of the beautiful itself." (Sallis, ibid., p. 392 - 3)

Dreaming, not knowing that the image is just an image (function of something else) but taking it to be the independently existing thing itself, the ordinary person thus does not really know the image: TouV ara polla kala qewmenouV, auto de to kalon mh orwntaV mhd'allwi ep'auto agonti dunamenouV epesqai, kai polla dikaia, auto de to dikaion mh, kai panta outw, doxazein fhsomen apanta, gignwskein de wn doxazousin ouden. (479 e) "And those who look at many beautiful things, but don't see the beautiful itself and aren't even able to follow the person leading them to it, and the many just things but not justice itself, and so on with all the rest -- we say that they opine all these things but know none of what they opine." "The implication clearly is that one could know the things which these men only opine, that is, that the knowable and the opinable are two modes in which the same thing shows itself." (Sallis, ibid.)

The eros of the philosopher, of the person who has caught sight of the (divine) condition of possibility of existence (in this case concerning the way things appear as what they are, their showing) and is therefore on the path toward salvation, the negation of his finitude -- to have the "dhamma eye open", in Buddha's words -- his eros is of a different direction than that of ordinary people. "On the one hand, the philosopher sees both parts of the whole, both the beautiful itself and the beautiful things, but on the other hand, his love is directed only to the first of these two parts." (Ibid., p. 395) Ti de au touV auta ekasta qewmenouV kai aei kata tauta wsautwV onta; ar'ou gignwskein all'ou doxazein; (479 e7) "And what about those who look at each itself and being always the same according to itself? Don't they know and not opine?" Knowing really things, why they are as they are (and whence they came), and the eros directed to this real rather than, as with ordinary persons, to the corrupt manner of showing (in Sallis' third sense) or to the virtual reality -- such is the beginning of salvation. "... only the philosopher is directed to the whole, for he alone is directed to a showing in which each thing shows itself as one, as a whole, rather than as divided up, though indeterminately, into many; and only the philosopher is directed to a showing in which what shows itself shows itself wholly, a showing in which it does not, in showing itself, also conceal itself by showing itself as it itself is not." (Ibid.)

Sallis is obviously arguing from the Heideggerian perspective. As said, the "theory of form" (in this third sense relating to why things are what they are) is valid only in the functional perspective within which Plato operates and in the structural perspective has to be replaced by Weltlichkeit and the laws of science. Here the detail of this transition (replacement) will be elaborated.

In the structural perspective this manner of explaining why things show up as what they are (explanation by reference to forms) is most retained in linguistics. As indicated, Saussure's distinction between langue and parole to explain how language operates corresponds exactly to the way Plato tries to explain how things operate to obtain their intelligibility (showing) for us. Saussure sees the total phenomenon of language (langage) -- corresponding to the whole showing of things here -- to consist in a synchronic side, a synchronic field, langue -- corresponding to forms --and a diachronic side, parole or speech -- corresponding to things. We may make a speech, "the stubborn and harsh professor is carrying his favorite suitcase today that looks quite ridiculous." This is possible -- for the speaker to utter this parole and for the listener to understand it -- only because it is a partial manifestation of the langue called the English language which has no real "objective existence somewhere", is never really totally uttered at any place on earth at any time, but which, of course, we all sort of understand, though imperfectly; it exists in a vague and imperfect manner in our head, i.e. in the heads of the community of English-speakers. Every speaker of English utters this speech somewhat differently from every other as each has a different accent -- no one can be said to pronounce the words so absolutely correct as to be the measure, the ideal, the embodiment of real English to which others pronouncing the same words differently are only approximating -- not to mention the non-native speakers who speak this same sentence with heavy accent. It can therefore be said that the actual utterances of the English langue, the diachronic showing of each English word in speech is only a corruption of the ideal, of the eidos of that word in the synchronic. The pronunciation of the words in actual speech is therefore exactly a showing forth of the English langue in which, in showing itself, it also conceals itself by showing itself as it itself is not. The langue itself, the English language as it is, according to itself, though making possible our speaking of it and the intelligibility of what we speak, is never "visible" (i.e. actually heard), but only "intellected" (noetized).

When we leave pronunciation and look at the sentence uttered in entirety, we see that the langue has shown itself here -- though also hiding itself -- not just in this phonetic aspect but also in the grammatical aspect. In the particular example we are using above the showing appears not to have concealed itself as well, since it seems grammatically perfect, without mistakes, both in terms of morphology and syntax. One can of course take issue with the "today", which, interposing between "suitcase" and "which", disrupts the ideal construction of relative clauses in English, should have been inserted elsewhere, say, in the beginning of the sentence, and in this sense makes this parole equally a corrupt showing of the langue: a showing of the English grammar as it itself is not. Theoretically a person can be found who has never uttered a single sentence with grammatical error. But even so, since the entire langue is never actually present, showing forth, in any acts of parole, the latter can be said to be always the showing-forth and at once concealment of the langue in both phonetics and grammatics. The language is always already here before the grammarians appear to study it, figuring out its phonetic and grammatical structures, i.e. explicitating what we always already unconsciously know but never really know. The grammarian, directed in his eros toward and explicitating the langue, therefore corresponds to the philosopher, and the ordinary person who just speaks without knowing why they speak what they speak -- why the words are pronounced this way, why every sentence they speak comprises a word denoting some thing (noun) and another an action of the thing (verb), why the nouns, in normal declarative sentences, usually precede the verbs which precede the objects -- this person doesn't really know his language, but only opines it, especially if s/he could not follow the linguist explaining these whys to him or her and even denies the existence of grammar (the whys) altogether.

But we all know that language changes through time. Saussure emphasizes that the changes of a language are not just "phonetic changes undergone by the signifier" nor "changes in meaning which affect the signified concept"; rather, the changes "always result in a shift in the relationship between the signified and the signifier". For example, "Latin necare 'kill' became noyer 'drown' in French... [where] the bond between the idea and the sign was loosened, and... there was a shift in their relationship". Language-change is "one of the consequences of the arbitrary nature of the sign". (Course in General Linguistics, trans. Roy Harris; p. 75 - 6.) What is remarkable about linguistic change is that it is precisely the corrupt showing of the langue in parole which reversely changes the langue to conform to the corrupt showing. "Modern German has ich war, wir waren, whereas at an earlier period, up to the 16th century, the conjugation was ich was, wir waren (English still has I was, we were). How did this substitution of war for was come about? A few people, on the basis of waren, created the analogical form war." In other words, they were making grammatical mistakes, the showing in speech of the eidos of the first person singular preterite (was) as it itself is not due to the "influence" -- we may say "co-presence" in this instance of speech -- of another eidos (the first person plural preterite). "This form, constantly repeated and accepted by the community, became part of the language [i.e. langue]." (Ibid., p. 97) Forms, therefore, are not as invariable as Plato has conceived it. What is beautiful may become ugly and what is ugly beautiful through time within a single culture and more strikingly across culture. Plato had not at his disposal at the time the help of cultural anthropology or the study of cultural change.

But in pursuing these whys, the linguist has to posit that English, as it is, i.e. as langue, is more or less an isolating SVO language. More or less, that is, it is itself only a corrupt and partial manifestation of a universal linguistic typology, of which each language (langue) in the world is only a manifestation of a part, and just about in all cases a corrupt, imperfect, approximate manifestation at that.

For an excellent full exposition of linguistic typology the reader is referred to Bernard Comrie's Language Universals and Linguistic Typology (2nd ed. 1989). "The order of constituents of the clause is one of the most important word order typological parameters... In its original form, this parameter characterizes the relative order of subject, verb, and object, giving rise to 6 logically possible types, namely SOV, SVO, VSO, VOS, OVS, OSV... [Now] the distribution of these types across the [approximately 5000] languages of the world [today] is heavily skewed in favour of the first three, more especially the first two..." (Comrie, ibid., p. 87) Furthermore, "Lehmann argues... that the order of subject is irrelevant from a general typological viewpoint", so that the most prevalent of all, SOV and SVO can be reduced to just OV and VO. (Ibid., p. 96) OV and VO thus seem like eidoi which show themselves in the majority of the world's languages. But that's not the end of the story. For OV tends to be, i.e. is typologically, associated with other word order typological parameters: adjective-noun (AN), genitive-noun (GN), postposition as adposition, prenominal relative (relative construction preceding the noun: RN), tendency toward suffixing of grammatical markers, post-(main) verbal auxiliary, and standard of comparison preceding the comparative ("than he bigger"). VO is then typologically associated with all the opposites of these: noun-adjective (NA), noun-genitive (NG), preposition rather than postposition, postnominal relative (NR), tendency toward prefixing of grammatical markers, preverbal auxiliary, and standard of comparison after the comparative ("bigger than he"). Moreover, OV languages tend to be agglutinating, and VOs isolating (with the inflectional being the type for languages transiting from OV to VO; c.f. Winfred Lehmann, Proto-Indo-European Syntax, 1974). Thus the eidos discerned to run through the two series of typological parameters is deteminant-determined or modifier-modified ("operator-operand or adjunct-head, dependent-head, modifier-head") for the OV and modified-modifier ("operand-operator, head-adjunct, head-dependent, head-modifier") for the VO type. (Comrie, ibid., p. 96)

Since, for example, Japanese and French are the two most consistently OV and VO among the commonly known languages, the two eidoi can be said to show themselves most purely -- i.e. with less mixture, in the least community, one with another -- in these two languages. Most other languages are somewhere in between the two series of typological parameters, leaning toward one end or the other: i.e. the two eidoi (modifier-modified and modified-modifier) show themselves in community with each other in these languages. So consider the following examples, first Japanese (TOP = topic marker, DAT = dative postposition, LOC = locative, ACC = accusative):

kanojo wa kinoo yuubinkyoku de shachoo ni tegami o dashita

that-girl TOP yesterday post-office LOC manager DAT letter ACC sent

"yesterday at the post-office she sent the letter to the manager."

This is the typical OV clausal word-order: subject, locative, etc. adverbial phrases, indirect object, direct object, verb. French would have everything reverse: j'ai vu la femme dans cette chambre ("I saw the women in this room") has its Japanese counterpart kono heya de kanojo o mita (this room-LOC that-girl-ACC saw). The two eidoi of word order showing up respectively in these two sentences are inverse of each other. But in German whereas the VO eidos shows up on the level of the main clause on the subordinate level (both in verbal phrase and subordinate clause) it is the OV eidos which shows up, so that in an instance of German speech (bodies, action; but of course this is because German is so in langue) the two opposite eidoi are showing in communion with one another: "die Frau sendt den Brief", but "die Frau hat in der Post den Brief gesandt" and "Ich weiss, dass die Frau in der Post den Brief gesandt hat". That is, though German is considered a VO language, the VO eidso is showing itself in it as it is not because in the actual instances of world's languages it is usually showing in community with its opposite, OV, just as the "beautiful" does in actual beautiful things in community with "ugly". Even in French, the OV eidos shows up in the pronominal constructions in communion with the otherwise predominant VO eidos, "je l'ai vu dans cette chambre".

In the matter of nominal constructions, as in the following relative and adjectival modification of nouns, the eidoi modifier-modified and modified-modifier again show up most purely in Japanese and French: "arawareta hito wa, kireiina shojo no kao o mita" (appeared [Past] man TOP beatiful girl-GEN face-ACC saw; "the man who appeared saw the face of the beautiful girl"); "l'homme qui est apparu a vu le visage de la femme blonde". In German langue, of course, both eidoi are active and each can appear in parole: "der Vorschlag, den Ich vorgestellt hat..." or "der von mir vorgestellt Vorschlag..." And so in auxiliary constructions: "boku wa omizutori o mi ni iku tsumori desu" (I-TOP omizutori-ACC seeing-DAT go intending is [=am]; "I'm intending to go to see [lit. go into the seeing of]) Omizutori [a festival]"); "je veux aller voir le festive". Or in quoted speech: "kare wa kanojo o mite, 'sensei wa shinda no ga?' to kiita" (he-TOP she-ACC seeing, 'teacher-TOP died PARTICLE INTERROG' that asked; "he, seeing her, asked if [that: to] the teacher had died"; in other words, subject, subordinate [quoted] clause, verb). In these instances the two opposite eidoi are showing up relatively unmixed in Japanese and French, but in English too they appear so often in communion with one another: hence whereas OV should appear in conjunction with adjective-noun (kireiina shojo: beautiful girl) and noun-postposition (sensei-ni: teacher to, "to the teacher") and VO in the opposite manner (la femme blonde, au professeur), in English adposition precedes the noun as a VO language should be ("to the teacher") but adjective precedes the noun also ("the magnificent duo"): the showing-together of modified-modifier and modifier-modified.

What is noteworthy here is that the "forms" of linguistic typology are invariable and grounded in logic itself (once things are named and the names come to be modified, a relationship of temporal succession appears between the modifier and the modified) and that language-change consists in the shifting frequency (or the degree of exclusion of other forms) with which these fixed forms appear in them. Perhaps similarly the change of langue due to conformity to the impurity of the showing of eidos that was earlier specified in the example of "grammatical mistakes" does not demonstrate the variability of forms but only the changing frequency of their showing in particular spheres?

From the example of linguistics it can be seen that science in general is the "project" of Platonic forms, attempts to account for why things in the temporal (diachronic) are as they are by searching for the synchronic ideal which -- is it always? Not sure yet -- shows and conceals itself in these things temporal and, in thus so showing, makes possible the things' showing themselves in the way they show themselves. "In Plato's Academy the Socratic quest for definitions was to be transformed into a programme of research, in which philosophical problems would be explored and settled with the objectivity and deductive rigour of mathematics" (Gallop, ibid., p. xv).

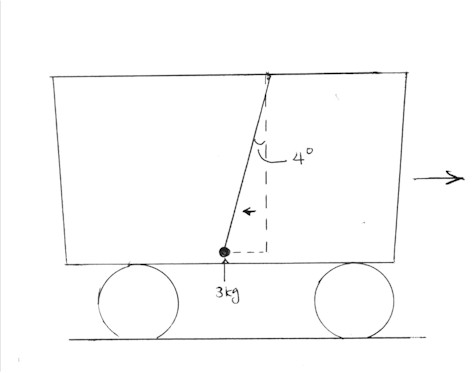

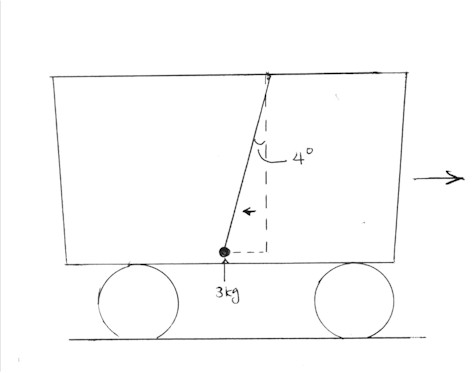

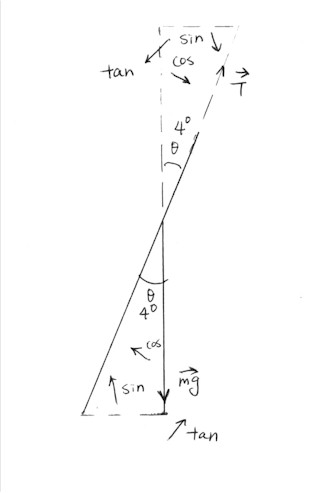

Let us, then, consider what the Platonists would do if the Academy had persisted until today, i.e. in the context of science; now I surmise, a Platonist would be fascinated with physics as the ultimate expression of the "Platonic project" -- that is, let us see how this project of forms corresponds with the laws of mechanics. The philosopher sees a cart accelerating, inside which a metal ball of 3kg hangs from a string and swings backward due to the cart's forward acceleration. All data of the situation are measured, i.e. perceived: angle of the swing 4 degree; acceleration of the cart 0.69m/s2. Seeing the cart moving, the philosopher as physicist defines momentum (as the "quantity" of the motion perceived [Descartes]) to be p = mv and force to be F = (mv)d/dt. That is, these are the "forms" presupposed (hypothesized) in the quantitative perception (measurement) of the moving cart. Where did these forms come from? What allows us to understand what we see as the cart moving and moreover to quantitatively perceive this? The Weltlichkeit and the decontextualization of it: hence it is said that the Platonic project of forms diverges, in the structural perspective, into Heidegger's analysis of Dasein on the one hand and, on the other, the laws of science on the basis of Weltlichkeit and as the completion of this: together they constitute, and complete, the Platonic project of forms at long last. Leaving Heidegger's phenomenology for later, let us see how, on the second tier, the quantitative perception of the moving cart in terms of -- and made possible by -- the eidoi p and F works.

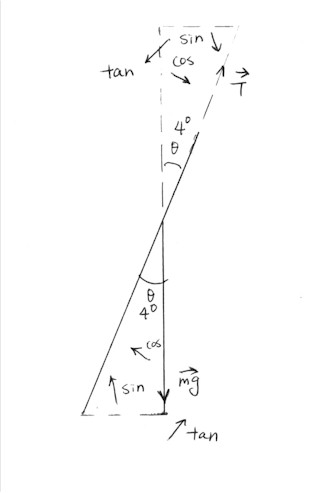

This perception, when reversely articulated, is the "solution" or "calculation" of a "problem". Here, for example, "find the acceleration a of the cart by knowing the angle of the swing to be 4 degree". It is after the "problem" is solved that we have all the "components" (data) of the perception: a vertical component of force which has two parts, the tension of the string and gravity (showing up as the weight of the metal ball), and which is 0, as there is no vertical acceleration, i.e. SFy = ma = T-> + mg-> = 0, so that the force of the tension of the string cancels out the force of gravity on the ball, Tcosq - mg = (T * mg / T) - mg = mg - mg = 0; and a horizontal component of force (the "moving" of the cart), Fx = ma = Tsinq = ma / T * T; now Tsinq / Tcosq = tanq = ma/mg, so that a = gtanq;(3) as tanq4 = 0.0699 and g = 9.8 m/s2, a = 9.8 * 0.0699 = approx. 0.685 m/s2 which is the acceleration of the cart.

The eidos ("form") F = ma which has made possible the physicist-philosopher's quantitative-structural perception of the moving cart, is thus showing itself twice in a vertical and a horizontal component. It is moreover showing itself in community with other "forms", here obviously those trigonometric functions describing the properties of a right triangle (the relationships of proportion between its sides called cosine, sine, tangent). As said, F = ma is itself the composite of two forms, derivative differentiation (d/dt) and p = mv. But it also shows up in this case of perception in community with still other forms, like w(eight) = mg (3kg = m9.8m/s2) which, though reducible as a variant of F = ma, contains the form g, which is not a pure form, but a derivative from (i.e. an eidos composed of) another, the universal law of gravitation G(m1m2) / (r2), and the mass of the earth (the form is actually just "mass" as density x volume). G is measured to be 6.673 x 10-11 Nm2/kg2 (Nm = Newton-meter);4 so the magnitude (the content of this form) of g is

| Fg = | G | Mearthmobject

(Rearth + h)2 | = (6.673 x 10-11 Nm2/kg2) ( | (5.98 x 1024kg)m

6.37 x 106meter | ) = m(9.8m/s2) |

which means g = 9.8m/s2 (h is the distance of the object from the surface of the earth). In other words, forms themselves (w = mg; Fgravity = G(m1m2/r2) are not "bottomless" but may trace their descent -- until some final point: ideally, where all laws of nature can be derived, as necessary, from, say, their mutual consistency. Whereas F = ma is definitional, tautological, so "bottomless" (in classical mechanics) G and the "inverse square law" are not and must derive from somewhere. (Of course once we ground these other "not-yet-bottomless" in the new physics the definitional character of F = ma might be lost.) Hence the point again: "forms" have to refer to a final Form good by itself and giving rise to all these minor forms not good by themselves but only in reference to that final Form. The "project of forms" of the Academy is thus continued by (after Dasein analysis) the projects of science in general and the clearest instance of the modern day "project of forms" is physics. The laws governing existence revealed in physics "remain always the same", and "clear and visible by itself" but are not directly seen but only intellected; thus they are "that which is" (o esti), just as the eidoi of linguistic typology are for the way languages are. But here the important issue arises. The "showing" of these laws in actual empirical circumstances are half-hidden, obscure, because, first, each shows up in community with other laws (and often each is itself a composite) and, second, there are "hidden variables". With the knowledge of the angle of the swing and the weight of the metal ball it is theoretically possible, by the reverse application of "forms" (F = ma), to know the acceleration of the cart, but in reality only approximately, due to the effects of friction which are not taken into account in the "calculation" (i.e. the reverse application of the eidoi). That is, not all the forms that show up in community with one another in this single case have been determined. But we have also discovered the laws ("forms") governing the workings of friction in the air, on solid surface, etc., so that theoretically still it is possible to get the absolutely correct calculation, i.e. the empirical phenomenon (the showing of the eidoi of Nature in actions and bodies through time) can be entirely reduced to "forms" and not just accepted as necessary corruption of forms (in the sense of Nature's eidoi showing but at once concealing themselves). "In classical physics, probability is used whenever the details involved in an event are unknown. For example, when we throw dice, we could -- in principle -- predict the outcome if we knew all the mechanical details involved in the operation: the exact composition of the dice, of the surface on which they fall, and so on. These details are called local variables because they reside within the objects involved." (Fritjof Capra, The Tao of Physics, p. 310) These details called local variables are the hidden variables considered here, i.e. those of which the "forms" governing their existence or operation are not taken into account but could be.

The ambiguity of the many, therefore, the showing of the form as it is not, is really just a problem of mixed showing of the many forms together in one empirical instance which obscures the showing of each of these forms. This is valid both of mechanics and of linguistics earlier, it seems. That a beautiful thing is one in which "the beautiful" shows but conceals itself at the same time because the thing also looks ugly is due to the fact that "the ugly" is also showing itself in this thing next to "the beautiful". The corruption of being by the beings embodying it (that beings are and are not at the same time in the third sense, i.e. in respect of showing, in the matter as to what they are) refers to the necessity that empirical things are just about always multivariously determined (by many forms at once) so as to be what they are.5 The concealment is the result of "showing in communion", not of showing in "bodies and actions" -- except in the sense that the laws of Nature are not themselves the things obeying them but are "imaged" by the latter. Therefore in a way we are refining Sallis' reading and in another way rejecting it.

The previous distinctions made then should be applied to the case of mechanics as much as possible. The laws of Nature, though each is one, show up as ambiguous (because of mixing) and many. The manner of communion in which they show up, and the way in which they show themselves only in images, make the things they govern neither this nor that, nor both nor neither. It is up to the Academician (the philosopher-physicist) to discover, as Newton is said to have done, that the law (eidos) governing the fall of an apple is one and the same as that governing the movement of the earth around the sun. The ordinary person who takes this diversity (ambiguity) of things for granted, and sees only the apple falling and the stars turning, but not gravity, i.e. falling, itself, is dreaming. In a sense, they are fooled by this and that falling, which are neither falling nor not-falling, nor both nor neither. When Galileo found, abstracting from all instances of falling, that any object dropped would accelerate by 10 meter per square second if friction from air was neglected -- that the distance that an object fell within a given time when dropped was equal to the number of seconds squared times 10 meter (d = t2 x 10) -- he was "awakening" to the eidos d = 1/2at2 governing all fallings on earth and which itself was rooted in still other eidoi. (Trigonometrie.) In the same way he was transiting from looking to naming, on the path of a "definitional quest" for the nature of Nature. Before this people were "opining" about falling things, and afterward the mechanists were gaining episteme of the movements of Nature -- by means of a power stronger than that with which ordinary people opined about motion. He was moving toward being (to on). What remains to be seen is how this definitional quest is supposed to lead to salvation.

The insight that modern science, especially physics, is the continuation of the Platonic project of forms must not be corrupted by the expectation that this implies the absolute determinism of scientific laws, i.e. determinism which "predicts" the outcome (by reversing the process of the discovery of the eidoi) in every empirical instance. Rather, it could very well be that the "form" is only predictive (i.e. descriptive of how things are) on the level of a large number of such instances, in the manner of probability. The author of "Platonic Forms and Modern Scientific Thought" made just this mistake. "Plato's concept of forms raises many interesting questions. The concept that everything in the physical world has a form or ideal theoretical existence seems fairly valid upon a cursory examination. A theoretically perfect model for an object created by a human is rooted in common sense. This, however, is largely due to the mathematical and geometrical relationships between a 'chair' and a constructed chair and a 'house' and a constructed house. [A rather vulgar understanding of what 'form' is] The form in terms of mathematics is much more easily identifiable than the abstraction involved in an organism's form. When brought to the level of science, this trend is more easily explored. The more mathematical science of physics is understandable in terms of mathematical forms. F = ma has a very definite mathematical relationship which transcends force relations in the physical world. My main objection, however, [concerns] the universal applicability Plato assumes from the mathematical validity of forms. Let's take the example of water. Someone who understands water only in terms of the wet stuff that comes out of the faucet obviously has an incomplete conceptualization of water's form. [So, to determine, how is it that water is as it is:] If water is reduced to two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom with covalent bonds, the idea of water is becoming more complete. We can still further investigate water, noting its dipole moment, free electron pairs, and characteristic hydrogen bonding, thus explaining its surface tension, its extremely high boiling point, and its incredible versatility for use in biological systems. At this point, we seem to have a rather well defined concept of water, theoretically bringing us closer and closer to the realization of its form. A further reduction of water, however, yields some disturbing results. Going from a molecular to an atomic level, we can describe much more of what exactly water 'is.' In the final analysis, however, we find that the electrons which account, at least partially, for every characteristic of water fail to find definition, or a form. [This is where the author goes wrong.] The only way to describe the multidimensional orbitals of electrons in water is through probability theory [referring to quantum mechanics]. History has seen the failure of the plum-pudding model, Bohr's orbital model, and every other definite model for the circulation of electrons. The only theory which adequately accounts for electron circulation in water, and thus, as a result, for all its more broadly recognized properties, is probability theory. Probability theory is, by the way, a method of saying, 'We don't know!?' An easy rebuttal to this objection is simply that we don't yet know the truth about electrons and water, and thus the form. [The problem of hidden variable, not all the forms have been accounted for.] This objection has no scientific basis. Any more accurate description of electron theory can become only more complicated and more 'uncertain' than the current probability based theory. [Whatever this means; the author is confused.] Another rebuttal is that probability theory is a mathematical model, thus it has a form. Probability theory, however, is not an abstraction. It is a concrete consideration of the likelihood of any event in the physical world taking place. This does not rest on some theoretical or abstract principle, but on an earthly consideration of mundane and observable phenomenon." The author is again confused. Born's reformulation of Schroedinger's wave equations into a probabilistic formula for finding the electron's position P = Y2 is just as much a "form" (i.e. an equation) as F = ma. Thus, we need to clarify the fact that hidden variables need not be present to account for the absence of absolute determinism. Consider the case of radioactive decay.

"Some elements are unstable, decaying via the weak interaction into other elements. Such substances are called radioactive. For example, Nitrogen-13 decays into Carbon-13 plus an electron plus an anti-neutrino. The tendency of an element to decay is expressed by its half-life. For example, the half-life of Nitrogen-13 is almost exactly 10 minutes. What this number means is that if we have a large 'pot' of Nitrogen-13 and wait 10 minutes one half of the Nitrogen-13 atoms will have decayed and one half will not have decayed. If we wait a further 10 minutes one half of the remaining sample of atoms will have decayed and one half will not [and so on]... For radioactive substances, one crucial factor in discussing the half-life is that we were discussing a large collection of atoms. What if we only have two such Nitrogen-13 atoms? Then if we wait 10 minutes... there is a 50% chance that one of the atoms will have decayed. So this is sort of similar to flipping two coins... Similarly for two radioactive atoms we could end up with both decaying, one decaying and the other not, or both not decaying. Imagine that after 10 minutes the atom on the right decayed and the one on the left did not decay. We ask a basic question: What is the difference between the two Nitrogen-13 atoms? The answer to this is trivially easy: one atom decayed and the other did not. A more interesting question is: What was the difference between the two Nitrogen-13 atoms before we waited 10 minutes? The answer to this better question is sort of hard. According to Quantum Mechanics there was no difference between the two atoms: we had two completely identical atoms but one decayed and the other did not. Einstein never accepted Quantum Mechanics, and this part of the theory is one of the reasons... If, with Einstein, we reject the idea that completely identical initial states can evolve to different outcomes, then we conclude that initially there must have been some difference, some variable, that distinguishes the two Nitrogen-13 atoms. To date all attempts to discover what that variable is have failed; thus we would say that there is some hidden variable inside the atoms. In Quantum Mechanics there are no such variables." (David Harrison, "Schroedinger's Cat") David Bohm devoted the latter part of his life to discovering the "hidden variables" in the quantum world. Our intention here is to emphasize that the very nature of a "form" may be that it determines how something is (e.g. the decaying of the radioactive element) only clearly in a large number of empirical cases but ambiguously (decaying or not decaying?) in each single case.

Another point of note in considering modern science, especially physics, as the modern version of the project of forms is to note that the new forms are meant to capture all four dimensions (space and time), whereas Plato's, only the three dimensions of space. Forms for dynamics (kinematics) vs. those for the static portion of reality only. In Heisenberg's words: "The Greek philosophers thought of static forms and found them in the regular solids. Modern science, however, has from its beginning in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries started from the dynamic problem. The constant element in physics since Newton is not a configuration or a geometrical form, but a dynamic law. The equation of motion holds at all times, it is in this sense eternal, whereas the geometrical forms, like the orbits, are changing. Therefore, the mathematical forms that represent the elementary particles will be solutions of some eternal law of motion for matter." (Physics and Philosophy p. 71 - 2; Physik und Philosophie, p. 55 - 6: "Die griechischen Philosophen dachten an statische, geometrische Formen und fanden sie in den regulären Körpern. Die moderne Naturwissenschaft aber hat seit ihren Anfängen im 16. und 17. Jahrhundert das Bewegungsproblem in den Mittelpunkt gestellt, also den Zeitbegriff in die Grundlagen eingeschlossen. Unveränderlich in der Physik seit Newton sind nicht Konfigurationen oder geometrische Formen, sondern dynamische Gesetze. Die Bewegungsgleichung gilt zu allen Zeiten, sie ist in diesem Sinne ewig, während die geometrischen Formen, wie z. B. die Bahnen der Planeten, sich ändern. Daher müssen die mathematischen Formen, die die Elementarteilchen darstellen, letzten Endes Lösungen eines unveränderlichen Bewegungsgesetzes für die Materie sein.")

Finally, Plato operates in the functional perspective in which "values" and "facts" are not distinguished in the way in which they are in the structural perspective. There something's beauty is just as much a part of its "being" as its intelligibility as that something (the beauty of a chair is an integral part of its chairness). In the structural perspective the value that something holds for a human being is to be seen -- together with its intelligibility as that something -- as purely a function of the Dasein-ing (our self-interpretation) which discloses the (lived) world in the first place, and it is to disappear in the "objective" world of science decontextualized from this lived world in the second place.6

Footnotes:

1. The Greek text from Platonis Opera, IV, Oxford Classical Texts. Translation adopted, with alterations whenever appropriate, from Allan Bloom's The Republic of Plato 1968, 1991.

2. "According to Aristotle (Metaphysics, 987b1 - 10, 1078b10 - 32), the theory of forms developed from inquiries by the historical Socrates into ethical concepts, such as 'good', 'just', or 'holy'... Socrates had... asked such questions as 'what is holiness?', in order to obtain a paradigm or standard, whereby to determine whether particular actions, or specific kinds of action, were holy or not. Traces of just such an origin for the theory can be seen in two passages of the Phaedo where forms are explicitly connected with 'questions we ask and the answers we give' (75d, 78d)." (David Gallop, in the introduction to Phaedo, ibid., p. xii) The eruption of the reality of eidos in logoi is the moment of fruition of the "quest for definitions" of what has hitherto been taken for granted, which appears during this same First Axial on the other side of Eurasia among the Confucians.

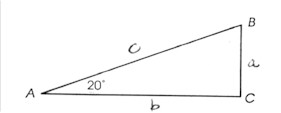

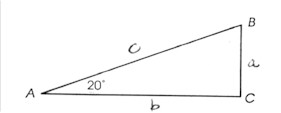

3. SinA = a/c; cosA = b/c; (a/c)/(b/c) = a/b = tanA.

4. "In... 1798... Henry Cavendish succeeded in measuring G in the laboratory with an extremely delicate experiment" described in Alexander Hahn's Basic Calculus, p. 196. G = 6.67 x 10-11 meters3/kg * seconds2

5. Fritjof Capra provides a very clear example of this in mechanics, in "a simple experiment that is often performed in introductory physics courses. The professor drops an object from a certain height and shows her students with a simple formula from Newtonian physics how to calculate the time it takes for the object to reach the ground." This is to demonstrate the eidos d = 1/2at2 showing up in this instance of "falling". "As with most of Newtonian physics, this calculation will neglect the resistance of the air and will therefore not be completely accurate." In other words, in this empirical instance of falling, the eidos for air-resistance has shown up also in communion with that for free-fall in vacuum to obscure the showing of the latter. "The professor may be satisfied with this 'first approximation', or she may want to go a step further and take the air resistance into account by adding a simple term to the formula." In which case another eidos has been named and made to show itself, clearly, itself by itself (it has stepped out of the shadowy realm of "hidden variables"); it is then added to the first eidos as co-determining the empirical instance in question. "The result -- the second approximation -- will be more accurate but still not completely so, because air resistance depends on the temperature and pressure of the air. If the professor is very ambitious, she may derive a much more complicated formula as a third approximation, which would take these variables into account." So a third eidos for temperature and pressure has been made to show itself and added to the first two. "However, the air resistance depends not only on the temperature and air pressure, but also on the air convection...." and so on (The Web of Life, p. 41 - 2). This is impossible. The empirical reality is a pale reflection or distortion of the realm of the forms in this sense, that it has mixed too many of forms in one instance so as to obscure the showing of every one of them.

6. The disjunction between "is" (facts) and "ought" (i.e. "values": both moral and aesthetic), first introduced by David Hume (in book III, part I, section I of his Treatise of Human Nature:), is the standard position in the analytic philosophy of today's English-speaking world. In the highly differentiated, structural perspective of analytic philosophers (the modern and postmodern perspective par excellence), any attempt to find the reason for what is right or beautiful in any part or the whole of the empirical world outside the human mind -- to make prescriptive or evaluative claims about what ought to be or what is better on the basis of descriptive statements about what is -- is considered a "naturalistic fallacy" (first named by the English philosopher G. E. Moore). A good text explaining the whole problem in analytic philosophy (of which our later genealogy of modern philosophy will make heavy use) is D. H. Monro's Empiricism and Ethics (Cambridge, 1967); see esp. Ch. 1, "Fact and Value": The question about "whether something did occur, and whether as the result of this something else occurred...." (e.g. "Is marriage, or has marriage been, good for women's happiness and finance?", or, equally, "Is the chair red?") "... can be settled by observation. In the final analysis we appeal, in answering them, to the evidence of the senses: to what we have observed to be the case in given situations. Moral questions [however] are not like this. Even if we could know with complete certainty just what the effects of banning a given book would be, there might still be room for argument about whether or not it should be banned..." (p. 5). Or, one may argue that slavery is wrong by appealing to the general moral principle that "whatever causes human suffering is wrong", or on the contrary that slavery is justified because it promotes civilization (by appealing to the general moral principle that "whatever is necessary for the promotion of civilization is right"), but in the end one cannot settle the dispute between these two general moral principles by appealing to evidences of the senses, because "moral conclusions cannot be drawn from factual premises alone" (p. 8). Nor can one settle the dispute between one who argues that "blonds are really more beautiful" and another who argues that "brunets are really more beautiful" by introducing factual evidences from the outside world. Our everyday acceptance of the disjuncture between facts and values in this case is codified in our saying "Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder" and in that case, "Often, what is considered right in one culture is considered wrong in another, and you can't say one culture is more right than another", i.e. in our sensitivity to cultural differences. The result is that analytic philosophers today distinguish between three possible types of statement (thesis, judgment): empirical statements about facts; value statements (which are either a. about beauty or b. about morality); and "analytic" statements (which include a. definitional statements, e.g. "bachelor is a unmarried male" and b. a priori and a posteriori statements). Both the factual and value statements are considered "synthetic", in opposition to "analytic".

What is important to recognize here is that the functional, less differentiated mind of the First Axial ancients (from Plato to the Confucians) cannot recognize all these distinctions. For them, you can indeed decide whether a certain human action is wrong or whether A is really more beautiful than B by looking into the empirical world. This is because, as you will see, beauty and morality are for the ancients (such as for Plato) not what they are for us today, but constitute part of the order of the cosmos, and order or disorder of the world outside your mind is a question about facts. If the Confucians consider son's obedience to the father or wife's obedience to the husband "right" it is because such action contributes to, and is an integral part of, the order of society, which itself is seen to contribute to, and be part of, the order of the whole cosmos (today's "universe"). It is only when the differentiation of consciousness breaks apart this ancient people's perspective of the cosmos that values become differentiated from facts, and, within values, morals (actions which affect the physical well-being of sentient life) from aesthetics (preferences which do not so affect, but are for mind-pleasing only). And only then can the distinction between synthetic statements and analytic statements be established. Only then, can "the gap between questions of fact and questions of value, between 'is-statements' and 'ought-statements'" appear, from which the "moral philosophy" of analytic philosophy arose (ibid, p. 3). Contemporary philosophy professors and students, especially in the Anglophone world, when they try to understand Plato with those modern categories in mind, necessarily corrupt the text. These modern categories of morals and aesthetics are highly impoverished versions compared to their ancient modes. On the other hand, the dispute about morality between the religious fundamentalists and the liberals reflects a similar, but not the same, situation. As mentioned, when the fundamentalists argue that "homosexuality is immoral" and the liberals simply can't see what is immoral about it, the former are really thinking about the order of society-cosmos and the latter about the physical (or even psychological) well-being of individuals. But though the fundamentalists perpetuate the ancient concern for order, this order has also been impoverished by the same differentiation of consciousness. We'll see this later. How the differentiation of consciousness has occurred as part of the constitution of the structural perspective through the de-animization of the cosmos will be studied in Division Two of our Scientific Enlightenment, and Western philosophy, especially analytic philosophy, would not take shape except within the milieu of such differentiation and structuralization (de-animization) of consciousness (or of the world). See Book 3.