|

Scientific Enlightenment

Introduction (1) Orientation in world philosophies and religions ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment

Introduction (1) Orientation in world philosophies and religions ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

Copyright © 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 by Lawrence C. Chin. Last revision: Apr. 3. 2007

This is the theme of this work. In this introductory space, we'll present the "peculiar" concepts that together constitute the conceptual framework by which we will describe, understand, and unify the diverse traditions and phenomena of human religiosity and philosophic endeavor.

The use of "peculiar" above means something. The disintegration of the past perspective together with the past traditions based upon it (the "shift in perspective" or "paradigm shift" later on) means that what people nowadays think the past philosophy and religions are about is not what they were actually about. (Throughout the current project this point, the problem of "forgetfulness", will be repeatedly emphasized.) Our conceptual framework, together with its conceptual components, is meant to re-construct the past perspective within which the authentic meaning of the past traditions can once again emerge. Hence they will appear "peculiar" against the background of the modern understanding of past thinking. The most peculiar component here is thermodynamics (or what the ancients thought of which today is formulated as thermodynamics).

The misconception of philosophy.

At this point the ordinary philosophy student would already have misgivings about classifying his beloved subject among religiosities of the world, which illustrates our point concerning the "forgetfulness" mentioned. Among world-philosophies, Western philosophy of the Axial Age is without doubt the most difficult for understanding, because hundreds of years of the development of modernity (the disintegration of the past perspective) have prepared for its distortion and destruction in Western academia. Hence let us set the matter straight before we begin our presentation. "Philosophy" was not, as the analytic philosophers would have us think, about "critical thinking" or "rational self-critical activity", i.e. clear thinking.1 Nor was it only, as the continental (European) philosophers frequently assert, the discourse about Being. But the purpose of philosophia as it was during the classical time, what it was about then, was eternal salvation of the soul (via the discourse, logoi, of Being): the negation of finitude or the "attainment of immortality". This is so, on the Greek side, from the Milesians (implicitly) through Orphism, Pythagoreanism, Parmenides, and finally to Plato. If we turn to Chinese philosophy, we'll find the same: Confucianism aside, the function of Daoist philosophy was salvation, although here the salvation was not distinctly "eternal" because of the empiricistic, hence immanentist, orientation so characteristic of the Chinese consciousness. The mark of eternal salvation in the philosophy of India (Hinduism and Buddhism) is the most pronounced. That the theme of eternal salvation no longer exists in the Western philosophy as taught in academia is due to the continuous formalistic (literalist, fundamentalist, propositional) degeneration of philosophy in the course of Western history, under the change-over of perspective or "paradigm shift" just mentioned.

The structure of salvation

Hence, in order to understand philosophy as it originally was, it is necessary to understand the structure of religiosity -- or rather the structure of salvation. It is probably better to speak of "salvational traditions" than of "religions". When one speaks today of "religion", one tends to have in mind Christianity, Islam, or Judaism, Buddhism or Hinduism, and tribal religions. One then wonders why the two sides are so different one from the other: Christianity (theistic) from Buddhism (often called the "atheistic" religion), West from East; and one ignores the greatest difference between all these salvational religions and pre-salvational, tribal religions. Knowledge of philosophy would teach that the salvational structure of Greek philosophy (from the pre-philosophical Orphism all the way to Plato), and that of Daoism as well, are essentially identical with that of Buddhism, which itself despite misleading doctrinal disputes is identical with that of Hinduism (in the pronounced forms of Upanishads and Advaita). There are thus two different approaches, systematically different one from the other, which human beings by the time of the First Axial had discovered as leading to eternal salvation (usually phrased as "immortality", meaning, "infinitude"): one consisting in waiting for the Divine, experienced as the Other, i.e. external, to intervene to "save" as a matter of Its Grace, and this at the end of history: the "revelatory" approach (Offenbarung, die geoffenbarte Religionen); the other in finding or "achieving" the Divine "within" oneself -- the Divine as the Same, the Self -- through intellectual work (hence the formulas Atman = Brahman, identity of the self with the Dao, or vision of the Agathon; or "immersion of the self in the Total", to put it inversely) and this at any time within history. These two opposing paths toward Divinity shall here simply be designated as the first and the second mode of salvation, and they carry each a host of oppositional characters respectively, which may be tentatively summarized in a table:

| First mode (Yahweh religiousness, Christianity, Islam) | Second mode (Orphism, Pythagoreanism, Parmenides, Plato, Hinduism (Upanishad & Advaita), Buddhism, Daoism) |

| Faith, in narrative stories of interpersonal relationship type (including with God) and in images of events and personages; that is, in a historical drama of salvation (creation, incarnation, resurrection, miracles; Christ died for our sins in order that we may return to God's eternal realm) | Reason, discourse ("theories") on the structure and nature of reality (hence the cosmogonic structure through numbers [Pythagoras], the discourse on Being [Parmenides], on eidos [Plato], and on Dao, the Dhamma [Buddha]). | Salvational Power as an external object, an Other, which gives salvation through Grace and interacts with oneself in personal ways (answers one's prayers, protects one, leads one, gets angry, etc.) | Salvation by finding the impersonal divinity within oneself, or, reversely, by identity with the whole or source of Being, through intellectual work (learning, knowledge, meditation: resulting in "the enlightened state of mind"). |

| Salvation is collective (salvation of an entire ethnic group [Israelite prophets] or of the entire humanity [or at least the "elect" part thereof: Christianity]) and hence world-historical (eschatology: a planned world-history ending in the redemption of all humanity or the elect thereof) | Salvation is personal, non-historical |

| In Weber's words (The Protestant Ethic): oneself as an instrument of God's will (as dramatis personae for the completion of the drama of salvation). Hence [at least with the Protestants] non-spiritual & un-emotional, non-compassionate, robotic, and prone to pass into fundamentalism/ literalization, where the Scripture becomes only a positivistic representation of present-at-hand objects [in Heidegger's words: Vorhandenes] and a positivistic record, in the surveillance-camera style, of events. | Weber: oneself as container of divine presence. (spiritual, mysticism, divinity as ready-to-hand-ness [Zuhandenheit] and not-a-thing) |

This field of oppositions is something like the universal structure of developed religiosity or salvation-proper (which tribal religiosity has not yet attained). With the opposite characters in sight, we may make the following observations: (1) the first opposition (faith vs. discursive reason) is not the same as the opposition (such as among the Catholics) between faith (in God) and reason (about God), in both of which God remains personal and external (Other). The faith referred to in the first mode is part of the very structure in which dramatic narrativeness and the externality of the divine hang all together with it, and the addition of theological reasoning to this drama and externality does not modify the basic, overall structure; whereas the reason of the second mode (logoi) is tied up in its very structure with the disclosure of the structure of reality and the immersion of this structure in divinity. One is blind belief (close mind), the other, learning, meditation, contemplation, reflection (open mind). Strictly speaking, the first mode is salvation without spiritual enlightenment, which hinges on the understanding of the structure and nature of reality and existence and which the testamental religions (in general, discounting their internal growth of mysticism and mystic tendencies) exclude rather than promote; while the second mode is precisely salvation through enlightenment. (2) The problem of number: the first mode has been quite accessible to the masses, to everybody, and hence has had much wider influences and many more followers, essentially because it takes the form of a story or drama (like the myths prior to it) and consequently is much easier to understand; but that the second mode on the other hand is difficult to access because its intellectual vigor (in knowledge and wisdom) makes it hard to understand: discounting Hinduism whose ritualistic form ("tradition") is intermixed with its philosophical, i.e. full-fledged salvational forms, only Buddhism subsists to today, the rest being passed down to us as "wisdom literature". (3) One may note furthermore that violence, intolerance, oppression, hatred and condemnation, aggressivity and libido dominandi, are frequently associated with the first mode but virtually never with the second (discounting Hinduism for now) which on the other hand frequently carries with it passivity and universal empathy and compassion for all sentient beings (hence vegetarianism: unwillingness to cause sufferings to animals). One never hears of "Buddhist fundamentalists" killing people in the name of Buddha.2 In the first mode followers' (Protestant Christians and sometimes Muslims) frequent display of arrogance and superiority toward people not of their faith and toward animals in general, is manifest a certain will-to-superiority and specialness (the "elect", the "saved", vis-à-vis the "damned"). The lack of compassion in the first mode seems to be related to its accessibility to the masses (hence its recruitment of the lower grade of humanity as well as the higher grade) and to its imposition of instrumentality on its believers (hence holy wars, struggles between good and evil people, etc.). (4) The tendency should also be noted which has always resided within the first mode, to transform itself into the second mode (hence gnosticism: salvation through knowledge; and mysticism: union with, immersion in, God, the Total, as the Same). This transformation seems to be a sort of "upgrading", bringing in also the characters of compassion and empathy from the second mode. The reverse transformation is never noted in the second mode. The task we set ourselves is the explication of how these differences have come about.

The origin of human religiosity: order, the sacred (the divine), and the soul in primitive religion

Under the influence of New Age eclecticism people often say today that "all religions are really the same", and so on. This is not true on the surface level of the relation to divinity, but it is true on the deeper level of the origin of the experience of divinity itself. Mircea Eliade writes that "le 'sacré' est un élément dans la structure de la conscience, et non un stade dans l'histoire de cette conscience." (Histoire des croyances et des idées religieuses, vol. 1. p. 7; "the 'sacred' is an element in the structure of consciousness, and not a stage in the history of this consciousness.") The statement is correct in that what constitutes human religiousness is a permanent structure of human consciousness -- i.e. the human experience of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos (our most important conceptual component) -- but wrong in that this experience itself undergoes evolution in regard to the precision of its content so as to produce the roughly Comtean stages of religion, philosophy, and science. The human experience of thermodynamics that is constitutive of human religious experience however has two aspects. One is conservation (the first law), and the other is the concern with entropy (the second law). The experience of divinity (the sacred) is the experience of eternity which is derived from the first aspect, from the human experience of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos in its conservational aspect. The human experience of thermodynamics is the necessary and eternal continuation, never increasing nor decreasing, of a "Total" (the Underlying, the substratum: the law of conservation of energy) despite the constant formation and dissolution within this Total of the many individuals (which form and de-form, as part of the entropy process, from and back into the energy-substratum). In human primordial experience, this experience of the sacred as the eternal and the Total is rightly associated with the experience of energy, as today we know that the never-changing "total amount of everything" in the universe -- that of which all things are made and to which all things can be reduced -- is just energy.

The second aspect of the experience of thermodynamics that is constitutive of religiousness is the experience of the thermodynamics governing the formation of macroscopic order -- order that, as dictated by the second law of thermodynamics, can only be formed and sustained as an open system with the influx of energy (i.e. in the mid-point of an energy gradient) stabilizing it away from equilibrium. Religiosity is at first constituted by the fear for this order, whether of the society or of the personal soul and preciously constituted uphill or against the arrow of time, to collapse back into the equilibrium of the environment. In primitive religions the order at issue is especially, and first of all, that of society, which is experienced as an open system on the model of an organism embedded in and dependent on a larger organism into which the cosmos is likewise hypostatized. Insofar as society depends on the nourishment from the cosmos, the order of the cosmos is second of all the concern of religiousness. In religious studies, the primitives' organismic view of society and the cosmos is especially taken up by Mircea Eliade.

There is a third component in the origin of human religiosity, and this is the notion of the continual existence of the soul (for which the compactification of metabolism-consciousness-breath into the pneuma animating the body is the original meaning). This notion is derivative of the first aspect of the primordial human experience of thermodynamics. Other than the intuition of the conservation (eternal continuation) of the Total, the first humans also have the conviction in the conservation (indefinite continuation) of the self which is experienced primordially as separate from the body, in the manner of Cartesian dualism. This is not so irrational: even when a contemporary scientist is asked if he believes that he will continue to exist after death, he will eventually have to admit that the atoms constitutive of his body -- and ultimately the energy stored as these atoms -- will continue their existence eternally because of the law of conservation;3 one sees that the difference lies in the application of thermodynamics within the functional or the structural view of the world. The primitives believe that the ancestors' "soul" continues its existence after death, for the same reason, in form blended in the cosmos and thus requiring propitiation (as we shall see, this is "animism"). This shows that they have already experienced this thermodynamic structure of the cosmos except that they mistakenly apply it to the breath-soul-consciousness rather than to the physical matter-energy whose arrangement produces this consciousness; that is, the problem is primitives' erroneous objectification of the complex of life-consciousness resulting in "ancestral ghost". The sacred, the cosmos entire, the Total, now takes on the character of a person, what we call anthropomorphism. Primitive religiosity is now at hand: just as the belief in the ancestral ghosts makes sense within the (erroneous) superficial application of thermodynamics, rituals in general and the propitiatory cult of the ancestors and deities in particular such as sacrifice can also be explained -- once the understanding of thermodynamics is, again, erroneously applied to superficial entities of the "spiritual" world with an egocentric perspective rather than to the underlying structural level of molecules, atoms, and energy with an objective (third-person) perspective -- as causal actions based on the thermodynamic operation of necessary infusion of (cosmic) energy into the social organism and into the cosmic organism to sustain their respective order. Now, since this energy and the cosmos have the attributes of a personality, this operation of the infusion of energy takes on the character of eating god or feeding god. The origination of the religious experience of guilt (or "sin") can also be found in the thermodynamic (material) meaning and origin of life and order in general, which implicate "debt" on various levels that any order and organisms must "pay". Of the two opposite approaches to explaining religions, the phenomenological (from Rudolf Otto to Mircea Eliade) and sociological (from Durkheim through Robert Bellah, Peter Berger, and René Girard to Nancy Jay, Chris Knight, and other fashionable contemporaries): although the phenomenon of primitive religions requires sociological explanations to exhaust itself altogether, the psychological reaction to thermodynamics (our version of the phenomenological approach) is here offered as the "core" and ideal structure around which other origins may be seen to accrue.

The motivation toward salvation and the differentiation of the salvational pursuit

In human history the differentiation from primitive religiosity occurs along three lines which result in the two fundamentally opposite modes of salvational pursuit.

The energy-operation that constitutes the core of tribal religiosity is aimed no more than at maintaining the order of existence here and now. It is a constant, periodic effort, just as eating maintains the order of the body for a moment only and has to be repeated at regular interval.

In Yahwism the prophets (eventually, after their harangue to their people fell on deaf ear) experienced the order of existence as permanently broken and unrenewable in time, and therefore differentiated eschatology: the renewal of order once and for all at the end of time.

Elsewhere the differentiation into salvational traditions developed rather on a personal level. Here the very structure of personal existence was called into question: frustration with the spatial and temporal limitations caused by their individuality and determined by the entropy process -- that they, principally, have to eat, defecate, and die: the problem of finitude -- came into the purview of an explicit reckoning. In Buddhism the tiresome spatial and temporal limitations were recognized in their derivative, "suffering". Then, when the experience of conservation reached clarity, human beings eventually came to the explicit reckoning of (a proper) conservation back into the Total, into the spatially infinite and temporally eternal which was their Source, so as to effect the extrication from the limitations of finitude: salvation. This structure belongs among the traditions of the second mode (specifically Orphism-Platonism, Hinduism, Buddhism, religious Daoism but not so much the philosophical Daoism in the beginning), as the early philosophical investigations invariably revolved around the problem of the apparent genesis and dissolution in relation with the underlying continuation, of the apparent individualities in relation with the hidden "Being as One".

There are great differences among the different traditions of the second mode in regard to their respective conceptions of the conservation of the soul within the Total -- differences that we shall examine in detail in the course of our study. These differences stem from their relatively more or less differentiated conception of the Total. Those who say in the spirit of, perhaps, New Age eclecticism, that every religion worships the same God, is correct to the extent that the divine is everywhere the eternal and the Total to which different traditions attach different names: a look at the pronouncements about Dao by the Chinese or Nibbana by Buddha or God by Ferdowsi or Agathon by Plato or Being (eon) by Parmenides or Lord Krishna by Arjuna (as param brahma param dhama in the 10th chapter of the Bhagavad-Gita As It Is) gives the sense that these are all describing the "same thing" (i.e. the eternal as the unvarying Total) as does Moses' passing of God's self-revelation as "I am who am" (ehyeh asher ehyeh). But the experience of eternity is subject to progressive differentiation toward increasing clarity: from the most immanent and compact experiences of eternity such as the Anaximandrian apeiron or the Upanishadic Brahman or the Chinese Dao or the Neo-Confucian qi through the more transcendental and differentiated expressions such as Parmenides' Eon, Sankara's Brahman, Arjuna's Krishna, and then Plato's Agathon and finally to the most differentiated of Buddha's Nibbana which dissolves into complete extinction, nothingness. Most of the doctrinal differences among the second modes -- resulting in the antagonism between the Hindus and the Buddhists or between the Neo-Confucians on one side and the Daoists and (Chinese) Buddhists on the other -- are caused by their respective degrees in this differentiation of the understanding of eternity. Within the first mode this thermodynamic origin of God as the Total is obscured by His externality (Otherness) because it is essentially the continuation, though in a differentiated, linear form, of the earlier primitive ancestor or deity cult, which, as seen, is itself based ultimately on the experience of thermodynamics.

What we should take great care in avoiding is the impasse of atheism. We have all heard of the atheistic way of denying an objective (external, empirical, out there in reality) foundation for the experience of "God": usually through some sort of psychologism, that "God" is the projection by the primitive, immature people of their parental figures (e.g. like Freud) or of their inner, not-yet acceptable self (Feuerbach), or the therapeutic fancy of people who feel weak and sick inside (Nietzsche), or the unwarranted extension of their inner psychological states onto inanimate reality, or the imaginary construction of perfection and immortality in frustration with self's own imperfection and mortality. The above however shows that all this is wrong, and wrong also is the literal, fundamentalist claim, that "God exists", i.e. a being called God exists in the manner that an intraworldly object exists.

The versions of the means employed among the traditions of the second mode for achieving conservation of the soul within the Total (i.e. the versions of asceticism) also vary widely, and this will be summarily addressed below.

Christianity, although of the first mode, was a mixture between late Yahwism (which is of the first mode) on the one hand and Hellenistic mysteries and Orphism (which are of the second mode) on the other. It combined the concerns of the second mode with personal salvation -- the negation of thermodynamic finitude, i.e. the acquisition of eternal life -- with the apocalypse and eschatology of late Yahwism -- the coming of God's kingdom and the resurrection of the dead at the end of time.

"Minor" salvation

In this work we will make an explicit distinction between what we shall call "major salvation" and "minor salvation". Major salvation refers to the eternal salvation of the soul, the primary objective of salvational pursuit. Minor salvation refers to the beneficial effects on the person in this life the assurance of eternal salvation afterlife will produce: the immediate, worldly benefits of the salvational state of the soul or mind. These usually come in the form of the order of the soul, the peacefulness of the mind, the non-attachment to the world of the senses and bodily pleasures, that is, freedom from the material meaning of life, resulting in easy living and "true happiness". The universal vehicle (means) for major salvation, "asceticism", is also universally the means for minor salvation or "true happiness". In Daoist philosophy (before religious Daoism) and the scientific enlightenment later on minor salvation is or may be the only realistic thing left since the afterlife of the "soul" is either not explicitly disengaged or no longer valid within the structural perspective, respectively. Scientific enlightenment, the goal of this work, is the search for a second mode of salvation within the milieu of science (the Second Axial prefigured, in a limited measure, by the proliferation of New Age spiritualities) just as the second modes of the First Axial did so within their milieu of the mythic world-view.

The various salvational traditions show further distinctions in respect to their respective modes of minor salvation. The worldly effect of Yahwism -- strictly speaking, Yahwism offers only minor salvation as it is a intraworld religiosity before its turn to the apocalyptic -- and Christianity is for example order, while the philosophies of Heraclitus, Zhuangzi, and Laozi promote enlightenment or the enlightened state of mind in the form of what Max Weber has called "Libesakosmismus", which Robert Bellah has translated as "world-denying love" ("Max Weber and World: Denying Love: A Look at the Historical Sociology of Religion" in Journal of the American Academy of Religion, June 1999, Vol. 67, No. 2, pp. 277-304.): "'World-denying love,' as opposed to worldly love, which is always love for particular persons, is love for all, without distinction -- love for whoever comes, friends, strangers, enemies -- which led Weber to quote Baudelaire in calling it 'the sacred prostitution of the soul.'" On the other hand, Buddhism and Platonism produce both order and enlightenment (specifically as the overcoming of illusion). This second distinction in minor salvation -- the order of the soul (or community: later) on one side and the overcoming of illusion and the enlightened love and acceptance of all on the other -- straddles over the first distinction between the first and the second mode. Among these systems there are further distinctions in the means for achieving minor salvation, i.e. a further distinction in their ascetic form. Yahwism and Christianity employ humility and humbleness so as to abide by the Law in the case of the former and to live by the Word of God in the case of the latter; this abidance and living-by then sets one's interior and/or society in order (and, in the case of Christianity, prepares the way for eternal life: only the righteous, i.e. the orderly, as is emphasized in the New Testament, will inherit the kingdom of God). But Buddhism employs contemplation on the truth of existence and Plato the eidetic study of the structure of reality in order to overcome illusion and produce order in one's mind or soul (and pave the way for Nibbana or the blissful existence of the soul among forms after its release from the tomb of the body). Heraclitus and the Daoists, finally, cultivate acceptance of the truth of existence in their "Liebesakosmismus".

Schema for the evolution of consciousness (as revealed by its salvational or pre-salvational orientation): the two stage, four tier process

Insofar as the goal of primitive religions is the maintenance of order (social or cosmos) in this world, it is not yet salvational, and hence it is pre-salvational or "intraworld" (in Weber's characterization) religion. The primitive intraworld religiosity being the milieu, salvational movements emerge from it (in the first and the second mode) with concern fixed on the other world, the world of infinitude-eternity after-life. We will designate the human perspective (the way in which humans see things) up to now as the functional perspective, and the two stages of development are its two tiers. The perspective logically and historically following the functional perspective and which makes possible the development of modern science we designate as the structural perspective. With the transition ("shift") in perspective from the functional to the structural, a de-animization of the cosmos occurs, causing the disintegration of the salvational religions and philosophies (which are only valid within the functional perspective associated with the more or less animization of the cosmos), and the rationalism of the nation-state encourages their secularization into either political movements or biopower technologies and institutions (c.f. "The process of secularization" in "Speculum Americanae"). These "secular religions" of modernity repeat primitive religions in a way since now human concerns are again focused on the prosperity in this world, on the happiness -- or rather productivity -- in this life. (Figure below.) For instance, in primitive religions the initiation rites are for the purpose of initiated individual's entrance into the tribe as an adult (i.e. as a functioning member). Other rituals maintain the order of the socio-cosmos. In salvational religions and philosophies the care and purification of the soul is for the purpose of the individual's entrance into Heaven or the divine realm beyond this world and after life (obtaining "eternal life"). But now the health (physical and mental) institutions are there to enable the individual to enter into the economic society as a "productive" member. Should there be a new emergence of salvational movements in this era of structural perspective, within the milieu of science, technologies, and modern politics, repeating those emerging in the era of the functional perspective, within the milieu of primitive religions and myths? That would be the Second Axial, which seems somewhat prefigured by the New Age movement. We may summarize human religiousness and salvational pursuit up to philosophy as thermodynamics of functional entities and modern science as thermodynamics of structural entities.

scientific enlightenment? ^

___________________________________________________________________ |

|struct-

political secularization of biopower institu- | ural

movements <------ religion: humanism ------> tions of health & |

(intraworldly & science living-standards |

messianism) |

________________"de-animization of the cosmos"_____________________ |_______

|

salvational pursuits |

| |

the first mode | the second mode |funct-

| |ional

______________________________|____________________________________ |

|

primitive (pre-salvational, intraworld) |

religions |

|

___________________________________________________________________ direction

of his-

tory

|

This progression of the spiritual meaning of history from intraworldly concerns in primitive times through otherworldly concerns during the Axial Age and back to intraworldly concerns in modern time has long been noted. For example, Robert Bellah:

|

The first of these [massive] facts [of religious history] is the emergence in the first millennium B.C. all across the Old World, at least in centers of high culture, of the phenomenon of religious rejection of the world characterized by

an extremely negative evaluation of man and society and the

exaltation of another realm of reality as alone true and infinitely

valuable. This theme emerges in Greece through a long

development into Plato's classic formulation in the "Phaedo" that

the body is the tomb or prison of the soul, and that only by

disentanglement from the body and all things worldly can the

soul unify itself with the unimaginably different world of the

divine. A very different formulation is found in Israel, but there

too the world is profoundly devalued in the face of the

transcendent God with whom alone is there any refuge or comfort.

In India we find perhaps the most radical of all versions of world

rejection, culminating in the great image of the Buddha, that the

world is a burning house and man's urgent need is a way

to escape from it. In China, Taoist ascetics urged the transvaluation

of all the accepted values and withdrawal from human society,

which they condemned as unnatural and perverse.

Nor was this a brief or passing phenomenon. For over two thousand years great pulses of world rejection spread over the civilized world. The Qu'ran compares this present world to vegetation after rain, whose growth rejoices the unbeliever, but it quickly withers away and becomes as straw. Men prefer life in the present world but the life to come is infinitely superior; it alone is everlasting. Even in Japan, usually so innocently world-accepting, Shotoku Taishi declared that the world is a lie and only the Buddha is true, and in the Kamakura period the conviction that the world is hell led to orgies of religious suicide by seekers after Amida's paradise. And it is hardly necessary to quote Revelations or Augustine for comparable Christian sentiments. I do not deny that there are profound differences among these various rejections of the world; Max Weber has written a great essay on the different directions of world rejection and their consequences for human action. But for the moment I want to concentrate on the fact that they were all in some sense rejections, and that world rejection is characteristic of a long and important period of religious history. I want to insist on this fact because I want to contrast it with an equally striking fact, namely the virtual absence of world-rejection in primitive religions, in religion prior to the first millennium B.C. and in the modern world. Primitive religions are on the whole oriented to a single cosmos: they know nothing of a wholly different world relative to which the actual world is utterly devoid of value. They are concerned with the maintenance of personal, social, and cosmic harmony and with attaining specific goods -- rain, harvest, children, health -- as men have always been. But the overriding goal of salvation that dominates the world rejecting religions is almost absent in primitive religion, and life after death tends to be a semiexistence in some vaguely designated place in the single world.4 World rejection is no more characteristic of the modern world than it is of primitive religion. Not only in the United States but through much of Asia there is at the moment something of a religious revival, but nowhere is this associated with a great new outburst of world rejection. In Asia apologists, even for religions with a long tradition of world rejection, are much more interested in showing the compatibility of their religions with the developing modern world than in totally rejecting it. And it is hardly necessary to point out that the American religious revival stems from motives quite opposite to world rejection. (Religious Evolution" in Beyond Belief, p. 22 - 3) |

As said in the beginning, we are interested, when we consider the evolution of human religiosity, in the perspective-shift that underlies this evolutionary process. As seen, we have divided this process into two stages (the functional and the structural perspective), with two tiers within each stage (the immature and the mature tier). The thinking is that the beginning of a perspective is always immature, and this immaturity is manifested as the inability to think of anything except as "things", on the analogy of tangible, measurable, empirical objects of everyday experience. Maturity (of either perspective) then consists in the ability to think beyond mere things. Hence the beginning functional perspective, the mythic, can only express its experience of the meaning of existence in myths, i.e. narrative of events involving things on the analogy of everyday life (e.g. toothache caused by worms receiving sanctions from anthropomorphic gods to go into the gum [Mesopotamian] or human beings coming from their molding by a female, therianthropic "god" [half-human, half-snake] out of mud [Chinese]). Since the testamental religions remain within the mythic bounds, the Judaic and Christian comprehension of the source of being (the Conserved or Being) and their breakthrough of ancestor- and deity-cult to reach salvation through this source are similarly framed in images and narrative (temporo-sequential) of things: God is like "a being", albeit transcendent, that "creates" the world and saves it by the "installation" of a "kingdom" of his, and then through "his son", who, job done, "ascends" into "heaven". When this functional perspective reaches maturity, it dispenses with the images of things and develops philosophic, mystic language of salvation through the Source: Plato, Buddhism, Hinduism (e.g. Advaita Vedanta), Daoism, etc., although entities from the mythic worldview ("soul", "levels of hell and the spirit world") sometimes persist in them. But note that the experience behind the imageries and symbolisms of the testamental religiosity, although of intraworldly things, is still ready-to-hand (zuhanden: immediately experienced, not abstractly contemplated). So is the mystical experience of the philosophic second mode. The transition from the functional to the structural perspective, completed in the West by the time of Enlightenment, has begun a new immaturity that has dispensed with the maturity of the functional perspective (beyond "things") and returned to the images of "things". This, however, is possible based on the presence-at-hand (Vorhandenheit) of reality previously disclosed by, e.g. sophism and Hellenistic sciences of the classical era.

Does geography explain the difference between the first and the second mode?

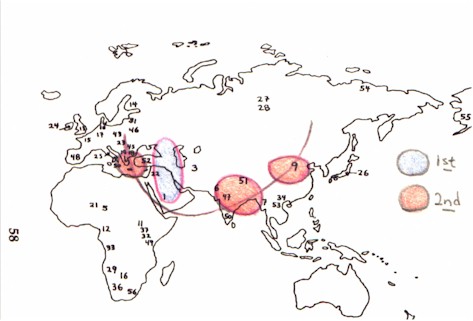

From the point of view of the second mode the "religions" of the first mode exhibit a thoroughly primitive character, largely because the personal nature of their relation to the divine as an Other confers upon their religiousness an "anthropomorphic" flavor, which by the standard of the philosophy of the Axial Time already appears unrealistic and childish. Why does one tradition differentiate in the direction of the first mode and the another in the direction of the second mode? One may then seek a geographical explanation for the divergence between the first and the second mode: a look at the map (below) shows that the first mode religions originated entirely in the Near East -- the region known for the sterility in terms of differentiation of human consciousness (Voegelin) -- and that all around and somewhat encircling this geographical origination of the first mode the second modes arose everywhere else, in the three fountain heads of philosophy: Hellas, India, and China. (We are not including the Persian contributions: Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism...) But in fact China can be considered also an arena in which the first mode could have, or almost, originated. An examination of the early Chinese sacred historiography (the oracle bone inscriptions, the Record of Poetry, the Record of Books) reveals that the Shang and the Zhou were evolving in the same manner as did the Hebrews towards a monotheistic historical mode of existence with the theme of a constant struggle between obedience and disobedience with respect to the will (order) of the Generic Ancestor (Di) which then constituted the source of order and disorder in the cosmo-society (the concern with entropy). But the empiricistic orientation of the Chinese (or inversely, their less fantastic imagination) did not permit the expression of the Generic Ancestor finally in terms of a transcendent "God" but caused it to settle onto the pantheistic, immanent expression of "Heaven". The Chinese were never very "metaphysical" in speculating about the "otherworld". The Chinese historical mode ("existence in the present under Heaven" thus in contrast to the Israelite historical mode constituted by the Sinaic Revelation, "existence in the present under God" in the words of Eric Voegelin) furthermore never had the fortune (or rather misfortune) to continue to differentiate into a salvational world-historic eschatology (i.e. the first mode) as had the Israelite mode in the hands of the prophets and the early Christians. Instead it simply fossilized into the cyclic "Mandate of Heaven". The second mode of salvation did however arise and blossom in China, even at the same time as the (failed) germination of the first mode, in the form of Daoism and its variants. What this shows is firstly that any people can develop the first mode as well as the second mode, and that the configuration of the current situation (a single strand of first mode traditions, one coming out of the other, surrounded by a variety of the second modes which originated multi-regionally) is an accident of history. It also shows that the Yahweh religiosity of the Old Testament must have evolved directly from an ancestor-cult just as the Chinese "Heaven religiousness" clearly did; the first mode was in fact just the most differentiated and advanced form of ancestor-worship, while the second mode -- philosophy -- broke out of the bounds of ancestor-deity cult altogether and was thus able to attain clarity of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos whose intuition had given rise to all religiosities in the first place.

The evolution of order (the "history of order")

Eric Voegelin's Order and History is the most important among the inspirations behind the conception of this work. When Voegelin announces the theme of his classic by stating that "the order of history is the history of order", he means order in a restricted sense: the type of ordering humankind at a particular epoch perceives the Total to be: "Every society is burdened with the task... of creating an order that will endow the fact of existence with meaning in terms of ends divine and human" (Israel and Revelation, p. ix). The intelligible structure of history is the successive civilizations' gradual approximation in their symbolization to "the truth concerning the order of being of which the order of society is a part" (ibid.). This is the spiritual meaning of history. The mechanism for the gradual approximation to the truth of the order of being is differentiation: the earlier symbolization of order is more compact and the later ones are the differentiated forms of the earlier one. Consciousness proceeds from compactness toward differentiation. We will, in the course of our study, have many occasions to emphasize, as Voegelin did, that differentiation is not an unqualified good; when an order differentiates certain of its aspects are necessarily lost which may prove to be among the greatest insights humankind has ever achieved.

The earliest form of order is that of the tribal and first state organizations (from those of the Ancient Near East to the earliest dynasties in China, and many elsewhere) with existence in the form of the cosmological myth. From this "cosmological order" differentiate the historical form of Israel and the philosophy of other civilizations as the symbolic form of order i.e. the first and the second salvational mode. We have three disputes with Voegelin, however. The first concerns the realization that, philosophy and Christianity being a salvational structure, it is sufficient for them to be carried on by a minority of spiritual souls "not of this world" such that they never become the symbolic form for an entire people. The prophets, the Christians, the Daoists, and the Buddhists in the beginning were all ignored or rejected by their fellow countrymen, although their symbolizations of the order of existence did eventually become the paradigm for an entire civilization (some, however, only for a time, such as Daoism for a brief period during the former Han dynasty). There is then Plato, whose "anthropologic" mode (in Voegelin's words) was never adopted by the Hellenic civilization as the form of order. We will refer to this phenomenon as the "stratification of consciousness".

Secondly, when Voegelin asserts in Israel and Revelation that the earliest type of order is that of the cosmological empire of the ancient Near East existing in the form of the myth he overlooks the fact that this cosmological order or cosmological mode characterizes also the order of tribal existence before the emergence of civilizations. Existence in the form of the cosmological myth had thus persisted for a hundred millennia or so as the way of human existence before breaking up under the differentiation of the first and the second mode of salvation during the Axial Age. Voegelin in his later years noticed this oversight on his part.

Thirdly, Voegelin in his conception of the spiritual meaning of history as the history of order failed to let the salvational accent therein come into precision. We mean to correct this shortcoming. The first half of our Scientific Enlightenment, the genealogy of the human pursuit of salvation up to the First Axial, is thus meant to improve on Order and History.

We would like to make an observation concerning the differentiation of the Axial Age. The most important characteristic of the order conceived for the beginning of the functional perspective -- the cosmological order where the experience of the cosmos is immediate and earth-bound -- is microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism: up to the stage of the salvational traditions, the structure of the macro-cosmos is replicated identically within the microcosmic human society at the upper side and finally within the microcosmic human body at the lower side. This structure is the axis mundi and the omphalos with the four corners. John Henderson has called this microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism "correlative thinking".

The Israelite differentiation -- from the historical mode of "existence in the present under God transcendent beyond the cosmos" to the mode of eschatology -- breaks apart the compactness of the cosmos as experienced in the cosmological mode: the compactification of human society and gods within the same sphere of the cosmos breaks up under the transcendence of God and the microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism consequent upon that compactification breaks apart under the linearization of time (although this concentric thinking later on re-appears in the mystic growth within the historical form, in Kabbalism and the symbolism of the Tree of Life). What is retained within the Israelite differentiation from the cosmological mode is, as mentioned, the personalization ("anthropomorphism") of divinity, which continues into Christianity. The differentiation within the second mode has a rather different, opposite result: philosophies of all origins -- Hellas, India, and China -- still operate within the compactness of the cosmos, within the structure of microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism (this can clearly be seen in Voegelin's designation of Plato's breakthrough as anthropologic: the tripartite politea replicating itself in both the human soul and in the polis) and the cyclicity of time. This is especially evident in the Chinese case, where both the ideology of Mandate of Heaven (the interpretation of the periodicity of the rise and fall of dynasties as their acquisition and exhaustion of the Mandate) and Confucian philosophy (for example Tung Zhongshu of Han) are strictly speaking recession back to the cosmological mode. What philosophy has broken out of is the personalization of the sacred: in philosophy the structure of reality has become transparent -- as much as it can be within the functional perspective: its impersonal, mechanical working in the most orderly manner was first cognized by the Milesian Presocratics, and eventually understood and studied as "laws of nature" under Pythagorean numbers and Platonic forms. The truth of existence embodied in this transparent, impersonal cosmos was contemplated upon on the other side of the world by Buddha and the Daoists. Thus, the disadvantage of the differentiation of the first mode is precisely the advantage of the differentiation of the second mode and vice versa. The two types of differentiation complement each other nicely.

Another differentiation within the cosmological order is the philosophic system of numerology. As consciousness differentiates within the bounds of the functional perspective, it subjects this microcosmo-macrocosmic concentric order to quantitative representation. Consciousness universally moves from qualitative to quantitative conception (see The Problem of Representation). The quantitative beginning is at the stage of the functional perspective manifested in the thinking about cosmic numerology and geometry. The Chinese case, where, for example, the royal capital has to be structured according to 9 and 5 (magic numbers capturing the structure of the cosmos) and be "squared" (as the earth is square and numbered 4 and the heaven circle and numbered 3), and the body similarly classified by 5 (e.g. 5 vital organs, homologous with the 5 planets in the heaven, etc., all of which replicate the 5 elements or phases), run through by the ying-yang forces (2) united in Taiji (1), is the numerology of the cosmological microcosmo-macrocosmic concentric order. (Other such "magic numbers" include 7, 10, and 12.) Within this kind of order the experience of conservation makes also necessary a certain "symmetry", like the one we see in the Yijing metaphysics of Sung dynasty. Numerology is the equivalent in the function perspective to the equations of physics in the structural perspective: both a project of the quantification of nature. Yijing metaphysics is the most conspicuous example of the quantitative representation of the cosmological order, just as Roger Penrose' The Road to Reality (2007) is an example of the quantitative representation of the structural universe. The "order" at the level of functional perspective is always compacted with all the macroscopic complex orders (i.e. of the biosphere) and based on the experience of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos. This is the theme of "Cosmic Numerology and the Conservational Principle." On the earliest, animistic stage, the macrocosmo-microcosmic homology is manifested in the magical practices of tribal peoples (through metaphoric and metonymic relationships the ideational content of the mind can influence the working of nature outside because of the perceived necessary replication, i.e. homology, between the microcosmos and the macrocosmos). By the time of the structural perspective, however, with the enlargement of the experiential horizon (from the earth-bound cosmos through the solar system to the Universe), the "order" itself and the macroscopic complex order above the geosphere become dissociated from one another: the "numerological order" of the cosmos sinks into the structural level of the subatomic constituents and the space-time fabrics to become complex "equations" governing the geosphere (such as governing the geometry of space-time [general relativity], wave-functions, the bosons and their symmetry-breaking, and strings). These laws or equations, although still ultimately based on the conservational principle (insofar as they have always to preserve symmetry), become increasingly independent of the second law of thermodynamics and the arrow of time; but the macroscopic order (biospheric [i.e. living organisms] and above) is now seen as the function of the second law in forming dissipative structures through self-organization and has within it no "inherent" structure, no "laws of nature" given squarely since the beginning of the Universe; e.g. "self-organization, the spontaneous emergence of order, results from the combined effects of [thermodynamic] non-equilibrium [e.g. difference between temperature from one locale to another], irreversibility [of chemical processes], feedback loops, and instability [at the bifurcation point where the system's behavior is inherently unpredictable]." (Fritjof Capra, The Web of Life, p. 192). This will come into focus in the history of science in Division Two. The consequence in the matter of "world-view" exerted by the enlargement of (empirical) experiential horizon can especially be gauged by a comparison between the "total system" of the cosmos constructed before and after the enlargement, e.g. between the Yijing metaphysics of Sung dynasty and Hegel's Enzyklopaedie (or more lately, Ken Wilber's), or, in respect to the more restrictive exposition of the mechanics of this cosmos, e.g. between Ptolemy's Almagast and Laplace's Exposition du Système du Monde.

-- The description of the functional and the structural perspective, which, with "thermodynamics", are so central to our conceptual framework -- which in essence amounts to a description of the evolution of consciousness of thermodynamics through the functional to the structural perspective -- has yet to be given. This will follow. After warning that the differentiation of consciousness is not an unqualified good, Voegelin remarks that amnesia with respect to past intellectual achievements is one of the most important factors in human history (Israel and Revelation, ibid.). This amnesia, this "forgetfulness", is precisely the result of the shift from one to the other of these two fundamental ways of seeing the world. As Thomas Kuhn has noted in relation to the structure of scientific revolution, each time that a paradigm shifts, the observer literally sees different things while looking at the same things, the old things having disappeared, as it were; and his "paradigm shifts" are merely micro-shifts in perspective within each of these two fundamental perspectives. In the next two chapters we'll make some general observations as to the harmful consequences of this shift in regard to philosophy and religions (which has caused the original religious and philosophic phenomena -- or eidoi -- to "disappear"): their propositional degeneration. The purpose of our project is both to save philosophy and religion from oblivion and to construct a "scientific enlightenment" proper to our modern perspective by using the recovered authentic meaning of philosophy as our guide.

This work is about spirituality. The human experience of thermodynamics is the origin of human spirituality. It is the anamnesis of conservation which has assured them the spiritual experience of consubstantiality ("All are One", "Being is One"), firstly among all pre-modern humanity, and then, even under the negative influence of fragmentation produced by positivism and more recently by consumerism, at least in a portion thereof. The "sacred" has always been this substratum of being as the One and the Source which is furthermore energetic, that is, it is the energy pool from which life and work draw their momentum and by which they become possible. But this spiritual experience of consubstantiality, as mentioned, has evolved in accordance with the evolution of our "worldview". In tribal time it is "animism", that the whole of cosmos is animated by life-consciousness-spirits which are ultimately One. Animism is the foundation of all forms of primitive religion (here is revived the ideas of the old master E. B. Tylor) and makes the first humans see the cosmos structured as a field of interpersonal relationships (between humans and supernatural spirits). By the time of civilization it has evolved into monotheism on the one hand and "pantheism" (e.g. the Milesian Presocratics) on the other. Pantheism can then pass into the depersonalized, mechanistic immanent monism (e.g. Daoism and Neoconfucianism) or the transcendentalist philosophies. In modern time consubstantiality takes the form first of the various formulations of the conservational principle in (the positivistic) classical mechanics (is the "total amount of everything" the quantity of motion? vis viva? the total mechanical energy of a system? and so on) and finally of the one conservational principle in Einstein's E = mc2. The "worldviews" or "paradigms" underlying the first two occur within, or are proper to, the functional perspective, and the worldview for the third -- and that for our fourth: scientific enlightenment -- within the structural perspective.

Footnotes:

1. For example, R. Bauer has taught that philosophy as "rational self-critical activity" consists in the two stages: (1) identifying one's belief state (beliefs, conceptions, etc.) about x; (2) evaluating this belief state for its rational adequacy, "whether the belief state is self-consistent, is justified by good reasons, avoids being contradicted by compelling counter-reasons, and avoids contradicting facts that we already know about the world... And you'll see in the coming weeks, much traditional and contemporary philosophy can be understood in terms of this two-stage activity." This is not what philosophy was about in the beginning.

2. A few exceptions in history can perhaps be named. There was the twisted Buddhist sect known as the White Lotus in 19th century China, which espoused an anti-Manchu millenarianism. Dating from the Mongol period, "the White Lotus Society appealed to the hopes of poverty-stricken peasants by its multiple promises that the Maitreya Buddha would descend into the world, that the Ming dynasty would be restored, and that disaster, disease, and personal suffering could be obviated in this life and happiness secured in the next." (Fairbank, China, 1988 ed., p. 189.) For the complicated details of this otherwise simple rebellious militant religious sect, see Elizabeth Perry, Rebels and Revolutionaries in North China, 1845 - 1945 (1980).

3. Note that the number of fermions (quarks and leptons) in the Universe is conserved, so that all of the quarks constituting the protons and neutrons of the atomic nucleuses of our body and all the electrons in our body have been in existence since they first crystallized out of the primordial hot-soup of Big Bang 12 - 15 billion years ago, and they will continue to exist as long as the temperature of the Universe remains lower than that of the hot-soup; it is of course within the stars of the first or second generation formed several billion years later that these quark-constituted protons and neutrons got squeezed into the heavier elements such as carbons and oxygens which today form our body.

4. Bellah of course is here reiterating Weber’s insightful characterization of the pre-salvational, intraworld religiosity of tribal humanity, this first human religiosity which he characterizes as “magical”: “Religiös oder magisch motiviertes Handeln ist, in seinem urwüchsigen Bestande, diesseitig ausgerichtet.” (Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft, Kapitel IV, Religionssoziologie, p. 227; “Religious or magically motivated actions are, in their original form, oriented to this world.”) “Alle erwürsige, sei es magische oder mystagogische Beeinflussung der Geister und Götter im Interesse von Einzelinteressen erstrebte, neben langem Leben, Gesundheit, Ehre, Nachfahren und, eventuell, Besserung des Jenseitsschicksals, den Reichtum als selbstverständliches Ziel, die eleusinischen Mysterien ebenso wie die phönikische und vedische Religion, die chinesische Volksreligion, das alte Judentum, der alte Islam und die Verheißungen für die frommen hinduistischen und buddhistischen Laien.” – “All the primeval, be it magical or mystagogic, ways of influencing spirits and gods in the interest of individual interests have striven for, next to long life, health, honor, progeny, and, possibly, the improvement of one’s fate in the hereafter, riches as the self-evident goal: the Eleusian mysteries just as much as the Phoenician and Vedic religion, the Chinese folk religion, the old Hebrew religion, the old Islam and the promise held out to the pious Hindus and Buddhist laity.” (Zwischenbetrachtung, Ges. Aufg. Zur Religionssoziologie, I, p. 544.) Although the Upanishadic Hinduism and Buddhism are properly speaking salvational, among the populous they have degenerated back to intraworld concerns; such compromise Weber sometimes characterizes as “organic social ethic” (organische Sozialethik).

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |