|

Scientific Enlightenment Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial 2.D.1. The Yijing Metaphysics of Sung Dynasty, China. Chapter 5: Yijing and the Five Phases ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial 2.D.1. The Yijing Metaphysics of Sung Dynasty, China. Chapter 5: Yijing and the Five Phases ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

copyright © 2003, 2005, 2006 by Lawrence C. Chin. All rights reserved.

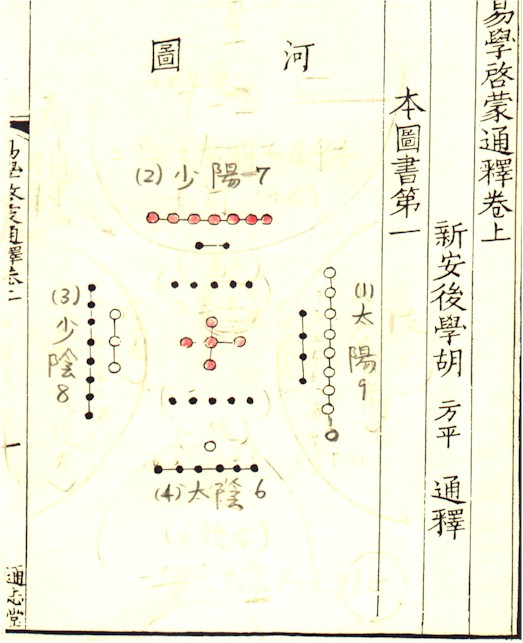

We have just considered the first component of the Yijing metaphysics typical of the Sung Dynasty: the hexagrammic system and the associated numerology. The second component to be considered is the system that combines the numerological systems called the (Yellow) River Diagram (left) and the associated Luo River Document with the philosophy of the five elements or five phases. (wu hsing 五行). The Yijing metaphysics of the Sung dynasty is the synthesis of all these diverse systems -- and more.

As with Hellas, the five elements, as the basic constituents of matter, of all the "stuff" in the cosmos, are to be explained as deriving from the basic human experience with the "states" of matter (solidity, liquidity, gaseousness, and the extra fire-like kind of existence) that are objectified into independently existing entities. But the Chinese evidently had made finer distinctions among solidity, distinguishing within it the softest, muddy kind (earth), the intermediary type (wood), and the hardest kind (metal), while also excluding the gaseous air (qi) as the conserved substrate from which these elements themselves came.

Fung notes the first appearance of the five elements in the Classic of Document (書經), but there "we find that the idea of the wu hsing is still crude. In speaking of them, its author is still thinking in terms of the actual substances, water, fire, etc., instead of abstract forces [i.e. phases] bearing these names [or manifesting themselves most appropriately according to the nature of each in these five substances], as the wu hsing came to be regarded later on." (A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 132, *p. 153.) The abstraction of the five elements into the five phases was what allowed the beginning synthesizing and syncretistic speculative mind of the Chinese "physicists" (like their Ionian counterparts) of the classical period to project them -- through artificial and extrapolative alignments that John Henderson (ibid) calls "forced fits" -- into the universal structure of the cosmos in both its spatiality and temporality, in the manner already seen. "South and summer are hot, because south is the direction and summer the time in which the Power or Element of Fire [Ultra Yang] is dominant [火德盛]. North and winter are cold, because north is the direction and winter the time in which the Power of Water [Ultra Ying] is dominant [水德盛], and water is associated with ice and snow, which are cold. Likewise, the power of wood [Lesser Ying] is dominant [木德盛] in the east and in spring, because spring is the time when plants (symbolized by "wood") begin to grow and the east is correlated with [i.e. the spatial manifestation of the same which is manifest in the temporal as] spring. The Power of Metal [Lesser Yang] is dominant [金德盛] in the west and in autumn, because metal was regarded as something hard and harsh, and autumn is the bleak time when growing plants reach their end, while the west is correlated with [the spatial reflection of the temporal] autumn... [Now as to earth:] According to the "Monthly Commands" [月令 in the Spring and Autumn Annals of Lue 吕氏春秋1: Periods of Warring Kingdoms]... Soil [earth] is the central of the Five Powers, and so occupies a place at the center of the four compass points. Its time of domination is said to be a brief interim period coming between summer and autumn." (Fung, ibid., p. 134) This sort of early and "immature" solution to the problem of projecting the 5 onto 4 through the division of summer in two to provide an extra season to be correlated with earth (also found in Huai-nan-tzu) was evidently to become unacceptable "to later systematizers inasmuch as it violated the requirements of symmetry. First it did not locate the season associated with the pivotal earth phase in the center of the year. Second it made the lengths of the seasons unequal by splitting only the summer while leaving the other three seasons unchanged." (John Henderson, The development and Decline of Chinese Cosmology, p. 11)

A better solution at this early stage is found "in the Yu Kuan (Office of Youth) chapter of the Kuan-tzu, [which] appears to have been graphic or geometrical rather than numerological. W. Allyn Rickett, following Kuo Mo-jo, supposes that this chapter, which consists primarily of a sort of seasonal almanac, was originally arranged as a chart in which the text for each seasonal division was situated in its appropriate quarter (as spring in the east), with the four segments arrayed about a central square. Each of the four seasons and four directions was correlated with one of the 5 phases, wood with east and spring, metal with west and autumn, and so forth. The remaining phase, earth, 'as the central element, was not correlated with any specific portion of the year, but was believed to operate throughout all four seasons of the year equally.' Thus it was placed in the center of the chart." (Henderson, ibid., p. 10; emphasis added.) This is the settled situation of the Yijing metaphysics.

The abstraction of the five elements into the five phases capturing also the temporal structure of the cosmos naturally requires them to hang together in a successive series as well. "The Ying-Yang school maintained that the Five Elements produce one another and also overcome one another in a fixed sequence. It also maintained that the sequence of the four seasons accords with this process of the mutual production of the Elements. Thus wood, which dominates spring, produces fire, which dominates summer. Fire in its turn produces soil [earth], which dominates the 'center'; soil again produces metal, which dominates autumn; metal produces water, which dominates winter; and water again produces wood, which dominates spring." (Ibid., p. 137) Again it is seen that at this early stage (the classical period, the Warring-states period) the extrapolative mind had difficulty with earth, with assimilating the cosmic 4 with the material 5 in total symmetry.

By the time of Han dynasty this "problem of the earth" was serious, as Henderson remarks: "A second major conundrum involving five-phase correlations arose from the problem of how to mesh the five phases with the four seasons (and four quarters). The effort to coordinate these sets of five and four deeply concerned Han cosmologists, for whom the phases, seasons, and cardinal directions were the very warp and weft of the cosmos, the chief markers of cosmic space and time. To fail to match properly sets as basic as these would have been almost tantamount to admitting that numerological cosmology, and systems of correspondence in general, were inadequate means of revealing cosmic order." (ibid.; emphasis added.) Let it be said at once that the origin of such "correlative thought" (as Henderson calls it) as the Yijing metaphysics is the attempt of consciousness to find a single, simple structure which is the structure of the cosmos by repeating itself at all (ascending and descending) levels or dimensions of reality: time, space, humans, human society, and human history; and which, therefore, through such self-multiplication in different dimensions and levels, results in the diversity of the cosmos as consciousness experiences it. This search for the universal cosmic order is essentially no different than the contemporary search for the "theory of everything" (as within the superstring theories) in the structural perspective. The functional perspective also believes that there is one structure of the cosmos which can be represented by numbers, and this is the correlative numerology that we are studying now. The difference is that the as yet immature consciousness has a simplistic and superficial (functional) view of reality ("everything"), just seasons, hours, cardinal directions, with the human society and human body as integral parts within these. And moreover the quantitative representation it seeks of this structure -- numerology -- does not go beyond ordinary arithmetic, which it attempts to "deduce" from numbers within the range of 10, the fundamental unit of the decimal system. This keeps the structure simple -- as the structure of the cosmos has to be simple, just as modern physicists believe -- but moreover it has to be beautiful, i.e. symmetric, hence consciousness seeks numerological orders within 10 that display symmetry. These shall be the (Yellow) River Picture and Luo River Writing (or Document) and the numerology of the 5 phases. Our strategy for the genealogy of these thus remains to derive the current Yijing metaphysics that is the synthesis of all these originally independent numerological systems from the memory of conservational principle: any aesthetic pursuit of symmetry is indicative of the projection of the principle of Conservation and any projection of this symmetry as the structure of the cosmos points to the realization by consciousness of the conservational truth of Reality.

Henderson continues: "Although most Han cosmologists meshed the 5 phases with the 4 seasons in a numerological manner, they, like the designer of the Yu-kuan calendrical chart, took the earth phase as the odd element in the system. This in itself suggested a solution to the problem, namely that earth be set apart from the other phases, and even invested with a physical primacy or moral superiority. Thus the Po-hu t'ung-i, arguing for the seminality of earth, points out that 'wood without earth does not live, fire without earth does not blaze, metal without earth is not completed, and water without earth is not elevated. Earth supports the humble and aids the weak to orderly complete their course." (ibid.) This work also provided another solution to the problem of seasonal correlation of the earth. "Pan Ku's Po-hu t'ung-i presented another numerological arrangement by which earth was phased in with the four seasons in a more symmetrical fashion. By this formula, an 18-day period was subtracted from the ends of each of the four seasons and allotted to earth, the cosmological rational for this arrangement being that each of the other phases, wood, fire, metal, and water, requires earth to consummate its work. Since 18 x 4 = 72, and 72 x 5 = 360, then the number of days of the year allotted to each of the five phases was equalized, even though this arrangement failed to account for approximately 5 & 1/4 days. [The Han astronomers had already estimated the length of a solar year to be 365 & 1/4 days.] This numerological arrangement, broached in the Po-hu t'ung-i and developed by the great T'ang era scholiast K'ung Ying-ta (574 - 648), came to be regarded as the most satisfactory solution to the problem. Thus whereas the older sections of the canonical medical text, the Huang-di nei-jing (The Inner Classic of the Yellow [Ancestor]), insert the earth phase in the last month of summer in the manner of the Huai-nan-tzu, chapters interpolated after the Han era allot to earth four 18-day segments falling at the ends of the seasons However, alternate arrangements continued to be devised in the post-Han era, as illustrated by the astronomical formula for meshing the four seasons with the five phases outlined in the 'Treatise on Astronomy and Harmonics' of the Wei History (Wei-shu...)." (ibid., p. 11)

What about the number 5 itself? Fung and many others attribute the beginning of the philosophic (cosmogonic and historiogenic) speculation based on the binary Ying-Yang and the five phases to Tsou Yen of the Warring States period (驺衍 305 - 240 B.C?), but such attribution may be an overevaluation. (Henderson, ibid., p. 34.) Five is the special number in the Chinese numerological metaphysics -- together with ten: as seen, 5 and 10 constitute the poles of being and non-being (Taiji), the minimal and the maximal. But 5 only emerged to become special through a process of competition with other special numbers -- which then should prevent wonder as to why the West has 4 but the East 5 elements. "In the pre-Han era, however, the wu-hsing was only one of several commonly used enumeration orders. Classical sources such as the Tso Chronicle (Tso-Chuan) and the Documents Classics (Shu-Ching) also record numerologies based on 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, and 12. Marcel Granet, noting the appearance of varied numeration orders in pre-Han texts, went so far as to link some of them with particular social groups or classes, 5 with the peasants, 6 with the nobility, and 3 with the urban military class. Granet's interpretation of divergences in pre-Han numerology is unsubstantiated, and in fact a good example of Durkheimian assumptions about the social basis of cosmology run amok. Nevertheless, it does raise the significant question of why five-based numerology eclipsed its rivals in the early Han era. One explanation might involve objective factors, for example the fact that five and only five planets are visible to the naked eye." (Henderson, ibid., p. 7.) To this might be added that the hand and foot are of 5, and hands and feet of 10. While the social basis of numerology is no explanation, deriving the special significance of a number from objective reality is certainly valid, since the goal of such search for "special number" is to find the one formula by which the whole cosmos and all existence is ordered. But we assert that the most important significance of numbers is their ability to represent symmetry, i.e. to express conservational principle. To return to the text:

|

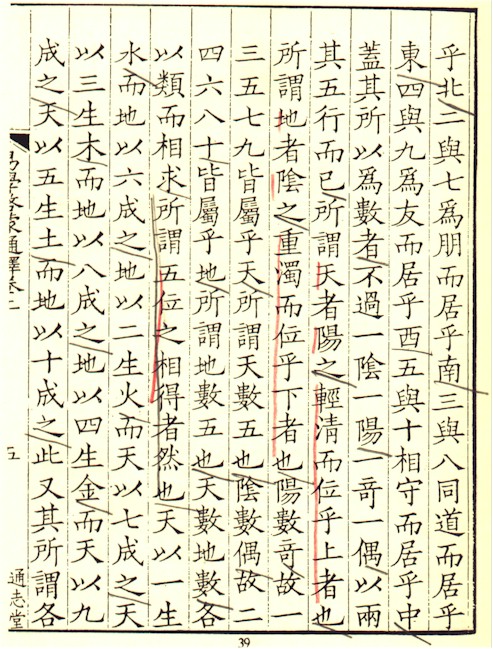

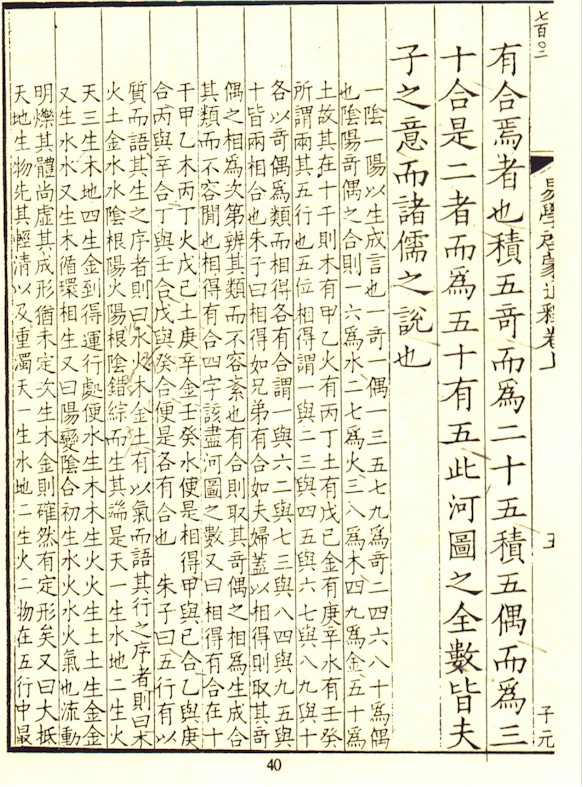

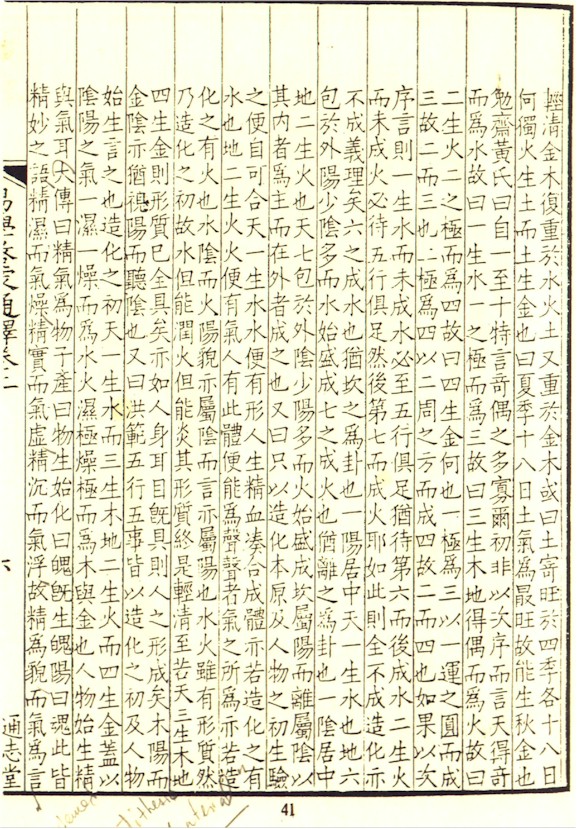

Heaven 1, earth 2, heaven 3, earth 4, heaven 5, earth 6, heaven 7, earth 8, heaven 9, earth 10. The numbers of heaven [are] five; the numbers of earth [are] five. The 5 positions [the five numbers of Heaven and the five numbers of Earth] each correspond with and complement each other. The number of heaven is 25 [1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + 9 = 25] and the number of earth is 30 [2 + 4 + 6 + 8 + 10 = 30]. The number of heaven and earth [i.e. of the cosmos in its entirety] is 55. With this, hence completion [of a being that's born: the become] and change [becoming: together the cosmic, Heraclitean flux] and [the established pattern of] the movement of ghosts and spirits. [These are citations from one of the appendixes to the Book of Change, 繋辭傳上, and what follows is the author's explicatory commentary on this.]

This section [explains] how the master invented the numerology of the River Diagram. Between heaven and earth there is only one qi [air; i.e. qi as the cosmic pneuma or air as the most primordial constituent of the cosmos, in the manner of Anaximenes, is the one substrate that manifests itself in heaven and earth. Hence qi, the substrate, is Taiji.]. It divides into two, giving rise to Ying and Yang. But the creation of all things by the five phases -- from the beginning to the end there is nothing it does not cover. The positioning of the River Diagram is therefore: 1 and 6 are of the same ancestry, hence located in the North.; 2 and 7 are friends, hence located in the South; 3 and 8 are of the same path [Dao], hence located in the East; 4 and 9 are friends, hence located in the West; 5 and 10 keep each other and are therefore located in the middle. The reason for such numerology is hence [the principle of] one Ying and one Yang, or one odd and one even, or the embodiment of the five phases by two. What is called heaven is Yang; light and thin, it therefore locates itself in the upper [level]. What is called earth is Ying; heavy and thick, it therefore locates itself in the downward [level]. [Note the similarity of this image to the Ionian physicists, and its general appearance in creation myths: it is a common sense experience that the lighter part, the masculine and "spiritual", i.e. "airy", ascends and the heavier part, the feminine and material, descends.] The number of Yang is odd, hence 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 all belong to heaven: what is meant by "the numbers of heaven are 5". The number of Ying is even, hence 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 all belong to earth: what is meant by "the numbers of earth are 5." The numbers of heaven and the numbers of earth, by [and because of] their nature, seek each other: hence what is meant by the 5 positions being mutually obtained is clear. Heaven with 1 gives rise to water, and the earth accomplishes it with 6 [making it a "become", complete]. The earth, with 2, gives rise to fire, and the heaven accomplishes it with 7. The heaven, with 3, gives rise to wood, and the earth accomplishes with 8. The earth, with 4, gives rise to metal, and heaven accomplishes it with 9. The heaven, with 5, gives rise to earth [mud], and the earth [ground] accomplishes it with 10. This is what is meant by each having a way of combination. The accumulation of the five odd numbers comes to 25; the accumulation of the five even numbers comes to 30. The two together come to 55. This is the total number of the River Diagram: the meaning of all the masters and the saying of all the Confucian scholars. |

We have two issues here, first the numeralization of the five phases and second the numerology of the (Yellow) River Diagram (and then of the Luo River Document). We shall deal with the first issue first.

As Fung remarks, the first numeralization of ying and yang then allows the metaphysicians of the Ying-Yang School to "connect the Five Elements with the Ying and Yang by means of numbers [i.e. the numeralization of the five elements as well]." (Fung, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, p. 140, *p. 161) The above "birth and completion" of the elements with the odd numbers of the Heaven and the even numbers of the Earth appears, for example, in Cheng Hsuan's (A.D. 127 - 200) commentary on the "Monthly Commands" (月令) in the Book of Rites (禮記). "This is the theory, therefore, that was used to explain the statement just quoted above: '[The numbers for Heaven are 5 and the numbers for Earth are 5.] The [5] numbers of Heaven and the [5] numbers of Earth each correspond with and complement one another.' It is remarkably similar to the theory of the Pythagoreans in ancient Greece, as reported by Diogenes Laeritus, according to which the four elements of Greek philosophy, namely fire, water, earth and air, are derived, though indirectly, from numbers. [Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Book VIII, ch. 19. Not surprisingly, since both the Yijing metaphysicians and the Pythagoreans represent that stage in the functional perspective of the cosmological civilizations where quantitative representation of reality or cosmogony is attempted.]" (Ibid., p. 141) The point is that, since Heaven is Yang and Earth Ying, Ying and Yang being the primordial constituents of the structure of the cosmos, their combination is to generate the next level of the constituents or the structure of the cosmos, the five phases, just as in the "cosmogony" of modern physics quarks and electrons (leptons) are to combine to generate the next level of the structure of reality, atomic nucleus with the shell of electrons around it to form atoms. "This [the numerological cosmogony with the five elements and the synthesis of them with other cosmogonic theories like Ying and Yang and the hexagrammic system], however, is in China a comparatively late theory [stemming from late Han dynasty], and in the 'Appendices' themselves [to the Book of Change] there is no mention of the Five Elements. In these 'Appendices' each of the 8 trigrams is regarded as symbolizing certain things in the universe. Thus we read in 'Appendix V' [說卦傳]: "Qian is Heaven, round, and is the father... Kun

is Earth and is the mother... Zhen

is thunder... Xun

is wood and wind... Kan

is water... and moon... Li

is fire and sun... Gen

is mountain... Dui

is marsh...'" (Ibid.)

As we have seen in the derivation, the intermediate trigrams are generated from the "crossing" between the extreme Yings and Yangs (represented by Qian and Kun). In the first attempt at hexagrammic representation of cosmogony, then, the -grams were supposed to correspond to things themselves, without the intermediate abstract principles of the five phases; the incorporation of the latter was the result of the tendency toward syncretism and synthesis of all cosmogonic systems and philosophies underway during the Han dynasty. Originally, the -grammatic cosmogony was likened to human birth through mother and father, the "crossing" of Yang (Heaven, father) with Ying (Earth, mother) producing offspring that were the "things" in the cosmos, which for the functional perspective were the immediately perceived things taken for granted, "water", "wind", "thunder", "trees [wood]", "mountain", "lake", etc., rather than the structures underneath these as in the structural perspective, e.g. limestones, salt and fresh water, the variations in atmospheric temperature and pressure generating wind and tornados, the elements of the periodic table, etc. The "likening" was possible because the process of human reproduction was seen by these cosmogonic speculators of the functional perspective as mimicking that of cosmogony: it operated also by the principle of "crossing" between Ying and Yang. "In Appendix III of the Book of Change [繋辭傳下] we read: 'There is an intermingling of the genial influences of Heaven and Earth, and the transformation [production] of all things proceeds abundantly. There is a communication of seed between male and female, and all things are produced.' Heaven and earth are the physical representations of the Ying and Yang, while Qian and Kun

are their symbolic representations. The Yang is the principle that 'gives beginning' to things; the Ying is that which 'completes' them." (Ibid., p. 142) Like Aristotelian conception of human sexual intercourse. This is the meaning of the above "birth" and "completion". The production of the 5 phases is better explained in the commentary:

|

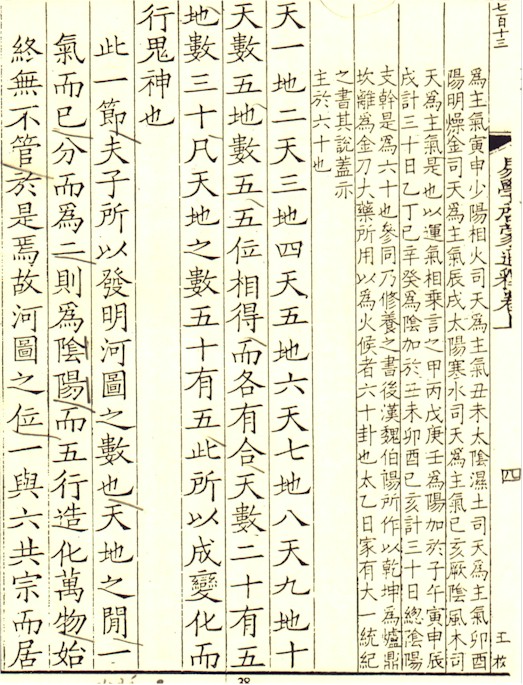

[The small print commentary:]

One Ying and one Yang are meant by genesis [lit. birth and the completion of what is born]. One odd and one even; 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 are odd, and 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 are even. The combinations of Ying and Yang, [i.e. of] odd and even, are therefore: 1 and 6 are water; 2 and 7 are fire; 3 and 8 are wood; 4 and 9 are metal; 5 and 10 are earth... [later on:] The order of genesis [of the 5 elements] is: Heaven 1 begets water; earth 2 begets fire; heaven 3 begets wood; earth 4 begets metal; when the place of the movement [of transformation] is reached, water begets wood [i.e. trees grow with water], wood begets fire [wood burns], fire begets earth [ashes left after burning], and earth begets metal [metal forms inside earth], metal again begets water, water begets wood, the cycle of mutual genesis thus continuing. [Zhu-zi] also said: Yang transforms and Ying completes, first begetting water and fire; water and fire are air [qi], flowing and shining, its body still indeterminate, the completion of its form [shape] still not yet determined. Next wood and metal are begotten, thus the shape is determined [determinate]. He also said: in general heaven and earth first beget the light and thin and then the heavy and thick. Heaven 1 begets water, then earth 2 begets fire; these two, among the 5 phases, are the most light and thin. Metal and wood are heavier than water and fire. Earth is heavier in turn than metal and wood. |

The order of production thus explained, the one last thing to note is the symmetry, or conservation, involved in it. Heaven, as Yang, is supposed to give rise to its opposite, the principal Ying, water, as a matter of symmetry in the manner of the pairing of the opposites (the mutual cancellation of the opposites to reach conservation) -- and the lighter and indeterminate coming first and 1 also first -- the earth then completes it with 6, since 5, the number of being -- 10 being Taiji, the source of being, in a sense non-being --is to be conserved. Heaven begets wood with 3, all the same, because wood is Lesser Ying -- the pairing of the opposite -- and Heaven completes it with 8, conserving 5, the number of being, formerly the cosmological constant or the minimal existence. The point is to look away from whether such numerical representation of the cosmogonic process makes any sense -- that is, whether it corresponds to any empirical reality in a meaningful way in the structural perspective -- and to consider its experiential motivation: in the human experience of the thermodynamic structure of the Universe, which expresses an order and expresses it in symmetry because of its conservational nature. Consciousness at the stage of the functional perspective, with a provincial horizon of experience, represents what it knows -- the cosmos with cardinal directions as its spatiality and the hours, seasons and eons as its temporality, and with the states (solidity, etc.) of matter as its principal elements -- and tries to find the structure, the order that it knows exists in the cosmos, which is the representation of it -- and moreover to do it quantitatively -- although this structure that it did find, when the experiential horizon has been enlarged after the transition to the structural perspective, seems simplistic and no longer meaningful as a representation, and is no longer seen as corresponding to the Universe.

Footnotes:

1. The Spring and Autumn Annuals of Lue:

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |