|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One

Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.1. Chapter 2: The origin of the elements of primitive religions (cont.): ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. One

Book 1: A Thermodynamic Genealogy of Primitive Religions 1.1. Chapter 2: The origin of the elements of primitive religions (cont.): ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

copyright © 2003, 2005, 2006 by Lawrence C. Chin. All rights reserved.

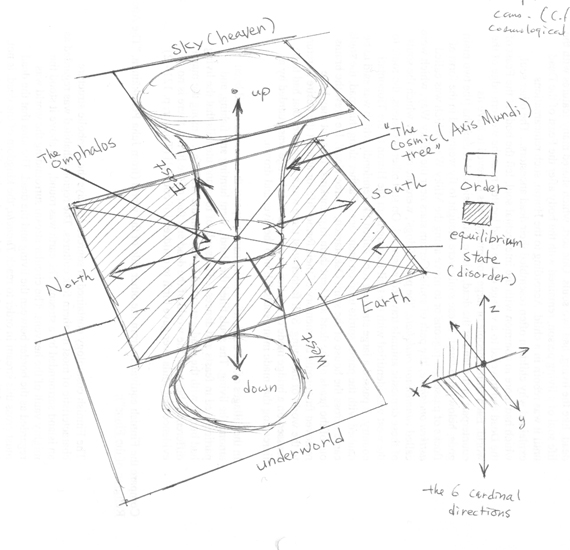

D. The spatiality of the cosmos in the functional perspective: the axis mundi and the omphalos. Mircea Eliade is famous for what he has referred to as the valorisations religieuses de l'espace, which are correlative with the agriculturalist cyclism and which lie at the origin of the symbolism of the omphalos (center of the world) and the axis mundi that is universally found among all pre-industrialized humanity. The valorisations are based on the "mystère de la sacralité cosmique... symbolisé dans l'Arbre du Monde... La 'réalité absolue', la rajeunissement, l'immortalité [i.e. the conservation of everything despite their dissolution and regeneration] sont accessibles à certains privilégiés sous l'espèce d'un fruit ou d'une source auprès d'un arbre." (Histoire des croyances et des idées religieuses, vol. 1, p. 53; "... mystery of cosmic sacredness... symbolized by the Tree of the World... The 'absolute reality', the making-young-again, immortality, are accessible to a certain group of the privileged through some kind of fruit or some [fountain] source near a tree.") Here, in the symbolism of the tree, lies as yet dormant the human salvational consciousness (preservation despite dissolution), to be differentiated out at later periods. "L'Arbre cosmique est censé se trouver au Centre du Monde et unit les trois régions cosmiques, car il plonge ses racines dans l'Enfer et son sommet touche le Ciel." (Eliade, ibid.; "The cosmic tree is supposed to be found at the Center of the World and unifies the three cosmic regions.") The cosmic tree is for the shamans the connection between the world of the living and the world of the spirits (dead) along which he may travel back and forth during his ecstasy, and, as the axis mundi, the vertical column extending upward and downward from the omphalos later on, the bridge between the divine and the human. This axis mundi however not only stands in the center of the world as the source of its order or as the seat of the omphalos and unifies all aspects of the cosmos that are not on the same plane of reality (the dead, the divine, and the living profane), but has furthermore the function of propping up the sky to prevent the differentiated order of the cosmos from collapsing back into equilibrium -- which it otherwise has the natural tendency to do in accordance with the second law of thermodynamics. The symbolisms of the god (such as the Chinese Pangu) or the four cosmic columns (also in Chinese mythology) incessantly and permanently propping up the sky to prevent its otherwise necessary fusion with the earth are variations of the cosmic tree and come from the same human experience of the precariousness of order given the second law.1

We'll see how this spatial structure of the cosmos (see Figure below) is manifested among the Germanic, Aztec, Chinese, and Northeast Amerindian (e.g. the microcosmic "shaking tent") religions -- not to mention its familiar versions from the Greek and the Mesopotamian context. For now as the most typical instances we mention the Finnish and the Iranian example. C.f. Pentikäinen: ibid.: "The cosmos was divided into three zones: the upper world, the middle world and the underworld. This tripartite structure is one of the oldest north Eurasian folk beliefs. The three cosmic planes were joined together by the cosmic tree, the cosmic column or the cosmic mountain located in the centre of the world. The top of the column was attached to the North Star, about which the heavens rotated. The Finns also likened the North Star to a hinge and spoke of the 'heavenly hinge', likewise the 'north pin', the 'celestial keeper', the 'pole star' and the 'heavenly pole'." And the Persian Homa: "The tree Homa is the tree of immortality in the Persian tradition. It is the vector of life; the creation of the world started around it. [La création du monde s'origine autour de lui.] The battles in which it is the object illustrate the universal cosmogonic fights. [Les attaques dont il est l'objet illustrent les luttes cosmogoniques universelles.]" (Corinne Morel, Dictionnaire des symboles, mythes, et croyances, l'Archipel, 2004.)

Eric Voegelin (in Order and History, Vol 1.: Israel and Revelation) uses the Hellenic term omphalos (the navel of the world) to designate the same tribal symbolism of the axis mundi (e.g. the Finnish case) continuing into the cosmological civilizations (e.g. the Persian case). Although these bureaucratically administered states have moved beyond tribal organizations, their religiosity (something like "state religions") is in structure not very different from that of the latter.2 The cosmological empires (e.g. the Mesopotamian states, Ancient Egypt, and less precisely the semi-civilizational kingdoms ["chiefdoms"] of Shang and [Western] Zhou in China and the Aztec empire in Mesoamerica), just like tribes, "were ordered in the form of the cosmological myth". Voegelin specifically defined the cosmological civilizations as symbolizing this order (the order of All: called nomos by Peter Berger in The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion, 1967) in concentric circles that modeled "society and its order as an analogue of the cosmos and its order" (ibid., p. 5; later we'll call such order "the magic politea"). Only later did he realize that this mode had been going on since the primitive, tribal time. This "analogic mode" is due to the ancients' limited experiential horizon. Society at this stage was experienced as an embedded component of the cosmos, as an outgrowth of nature, so to speak, and as co-evolving with, and replicating the structure of, the cosmos: the microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism. Even such a contemporary scholar in the trend of the sociology of religion as Chris Knight who has been most original in speculating on the origins of religion and rituals but who however has paid no attention to the role of the cognitive structure of the primitive (functional) perspective in the genesis of the religious worldview is trying to speak of the same microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism -- and the consequent validation of the attempt to use rituals (either purely theatrical or involving the use of physically energetic material such as animal or plant sacrifice) to fight against the macrocosmically perceived entropy-increase in nature or the socially felt entropy-increase in the social order -- among the Australian Aborigines when he says:

| In this scheme of things, human and natural cycles of renewal are mutually supportive and sustainable through the same rites. The skies and the landscape are felt to beat to human rhythms. Everything natural, in other words, is conceptualized in human terms, just as everything human is thought to be governed by natural rhythms. (Blood Relations, p. 465.) |

The structural components of the cosmological symbolization of the human (political) order correlative with the cosmological empires or kingdoms are (following Voegelin): in terms of time, space, substance, and center (omphalos). In terms of time, the founding of the political order of the empire was conceived of as "an event in the cosmic order of the gods", being part of the cosmogonic process itself, and therefore "referred back to the beginning of the world"; in terms of space, "the spatial organization of the empire reflects the spatial organization of the cosmos", resulting in the four corners of North, South, East, and West; in terms of substance, since the political order was part and parcel of the cosmic order, the king was then the ordering principle of this political order just as god was it for the cosmic order, with divine, ordering substance flowing from the divine to the king; finally there was the center (omphalos) from which this flowing of the divine to the social happened: in Greece it was Delphi, in the Babylonian empire it was Babylon, in China it was designated, during the late Zhou, by "Central (or Middle) Kingdoms", those kingdoms descending from the Zhou confederation which constituted the realm of civilization (order: the local concentration) surrounded by barbarians (disorder: the dissoluted or equilibrium state). (Ibid., p. 25 - 30.) This spatiality of the cosmos of the tribal peoples up to the cosmological empires (the omphalos with the axis mundi at the center of the field of the cardinal directions) has its origin in the second aspect of the thermodynamic experience constitutive of human tribal religiousness: The omphalos (whether it be Israel, the Middle-Kingdom, Hellas, or the temple-sanctuary of whatever tribes and kingdoms) is the island of order (pure, good) within a surrounding of increasing disorder represented by other nations (whether it be the Gentiles or the barbarians in the Hellenic or Chinese sense: the evil, unclean, corrupt, raw, disordered state), with the attendant fear for this order, preciously constituted uphill or against the arrow of time, to collapse back into equilibrium with these surrounding-nations.

| The primitive conception of space or spatiality (from the tribal stage up to the cosmological civilizations), which we'll see to be common to the Germanic, Chinese, Mesopotamian, Amerindian, and Mesoamerican peoples. |

E. The recapitulation of the spatiality of the cosmos by its temporality (or vice versa) due to the microcosmo-macrocosmic concentricism. Consider Mircea Eliade's description of the temporality of the cosmos:

|

Chez certaines populations nord-américaines, cette solidarité cosmico-temporelle est révélée par la structure même des édifices sacrés. Puisque le Temple représente l'image du Monde, il comporte également un symbolisme temporel. C'est ce qu'on constate, par exemple, chez les Algonkins et les Sioux. Leur cabane sacrée qui... représente l'Univers, symbolise en même temps l'Année. Car l'Année est conçue comme une course à travers les quatre directions cardinales, signifiées par les quatre fenêtres et les quatre portes de la cabane sacrée. Les Dakota disent: "L'année est un cercle autour du Monde", c'est-à-dire autour de leur cabane sacrée qui est une imago mundi. (Le sacré et le profane, Gallimard, p. 64.)

(Among certain North American populations, this cosmico-temporal solidarity is revealed by the very structure of sacred edifices. Since the temple represents the image of the World [i.e. the temple as the microcosmic replication of the macrocosmic Cosmos], it contains as well a temporal symbolism. This is what one can confirm, for example, among the Algonquians and the Sioux. Their sacred cabinet which... represents the Universe, symbolizes at the same time the Year. For the Year is conceived of as a course through the four cardinal directions, signified by the four windows and the four doors of the sacred cabinet. The Dakota say: "The year is a circle around the world", that is, around their sacred cabinet which is an imago mundi.) |

We will see how this repetition of the spatiality of the cosmos in and as its temporality -- and that spatiality as well: these two defining marks of the world-view of the functional perspective -- reaches its speculative limit and most mature quantitative formulation with the Chinese yijing metaphysics of the Sung dynasty. Underlying both the Dakota saying and the yijing metaphysics is the following coincidence between the structure of space and that of time (¤ being the omphalos).

winter-north

|

|

autumn-west -----¤----- spring-east

|

|

summer-south

|

Eliade further notes that, in India, insofar as the construction of a fire altar corresponds to a cosmogonic event, i.e. is a ritual act that regenerates the cosmos (below), the spatiality of the altar, in repeating the spatiality of the cosmos, also repeats the temporality of the cosmos. "Or, les textes ajoutent que l'autel du feu est l'Année'... les 360 briques de clôture correspondent aux 360 nuits de l'année, et les 360 briques yajusmati aux 360 jours (Catapatha Brahmana, X, 5, iv, 10; etc.)." (Ibid., p. 65; "Now, the texts add that the altar of fire is the 'Year'... the 360 bricks of the wall correspond to the 360 nights of the year, and the 360 bricks yajusmati to the 360 days...")

F. The organizational principles of the "anima system" ("pantheon"). The experienced tension between the everlastingness of the undifferentiated total and the ephemerality of the individual orders which characterized the primitive human experiences frequently transited to the tension between order and disorder, between good and evil, through the confusion between conservation and the internal "autopoietic" equilibrium of the ordered system. The (frequently confused) experience between good (order-formative and -preservative) and evil (order-dissolutive) is the prime organizational principle for the variety of gods. A most explicit formulation in the Zoroastrian salvational differentiation may serve as illustration here. The monotheos "Ahura Mazda est le père de plusieurs Entités (Asha, Vohu Manah, Armaiti)", the "Archanges" corresponding to the elements (fire, earth, metal, etc.; Mircea Eliade, Histoire des Croyances et des Idées Religieuses, Vol.1, p. 324). This is already philosophical and not cosmological. But Ahura Mazda then generated the twin Spenta Mainyu (the good-ordering, "l'Esprit Bienfaisant") and Angra Mainyu (the evil-destructive-disorder). "À l'origine, est-il affirmé dans une gatha célèbre (Yasna, 30), ces deux Esprits ont choisi l'un le bien et la vie [i.e. the ordering, or the creative of order], l'autre le mal et la mort [dissolution of order]. Spenta Mainyu déclare à l'Esprit Destructeur au 'commencement de l'existence': 'Ni nos pensées, ni nos doctrines, ni nos forces mentales; ni nos choix, ni nos paroles, ni nos actes; ni nos consciences, ni nos âmes ne sont d'accord' (Y. 45: 2). Ce qui montre que les deux Esprits sont différents -- l'un saint, l'autre méchant -- plutôt par choix que par nature." (Ibid.; "In the beginning, so it is affirmed in a famous gatha... one of these two gods had chosen the good and life, and the other, the bad and death. Spenta Mainyu declares to the destructive god in 'the beginning of existence': 'Neither our thoughts, nor our doctrines, nor our mental abilities; nor our choices, nor our words, nor our acts; nor our consciences, nor our souls are in agreement... This shows that the two gods are different -- one the saint, the other evil -- rather by choice than by nature.") What is important for our purpose is that the good is the conservative and ordering (self-organizing: the intermediary stage in non-linear entropy-increase) forces compacted together, and evil the disintegrating forces of the second law (only its linear entropy-increase!). That is, although the ancients were aware that order could only exist as an open system with constant energy-input to maintain its state thus stabilized away from equilibrium -- hence all the mythic imagery of a god spending energy supporting the heaven from collapsing back to the earth (back to the original equilibrium state) or of gods standing guard to prevent the equilibrium forces from invading the cosmic order and reaching equilibrium with it, e.g. the Chinese Pangu myth and the guarding of the dead Tiamat's water in the Mesopotamian enuma elish (all this later) -- they had mistakenly identified this maintenance through input with the conservation of the first law. Compact consciousness confused the basic anamnesis of the thermodynamic structure of the cosmos, conservation despite genesis and dissolution, with the conservation of order itself through energy input, this confused whole being collectively symbolized by the good, the ordering and creative force. An example of this can be found among the Nentsy, a Samoyed people of Western Siberia. "In the Nenets religion Num [the sky god] is the father of Nga, the god of evil and of death [hence representative of linear entropy-increase], and is therefore his antipode." (Robert Austerlitz, "Num", in Encylopedia of Religion, ed. Mircea Eliade, vol. 11, p. 12) Here the highest god (the first law) does not further differentiate himself into the dual gods of good and evil (non-linear and linear entropy-increase) but is compacted of the two aspects of the good (conservation and non-linear entropy). Even more compact is the related Selkup, among whom "Nom is the highest god but does not participate in a polar opposition; in Selkup nga means simply 'god' [like the Indic deva and asura]." (Ibid.) On the other hand, modern science (e.g. the study of complexity and self-organization) has revealed order-formation to be the non-linear entropic function of the second law, while the destruction of order to be its linear function. Thus the Zoroastrian account above was very advanced mythically compared to the other, average myths (such as the Nentsy) in that it split the good into two representatives: Ahura Mazda above would represent the ultimate good, conservation of the first law, Spenta Mainyu the order-formative intermediary stage of non-linear entropy-increase (the second law; intermediate in the sense of an extra transitional stage between the local concentration of energy and the equilibrium without any local differences), and Angra Mainyu the order-destructive linear entropy-increase (still the second law).

Good | Evil (Ancient)

conservative order-formative | dissolutive

----------------------------------------------------------------

1st law | 2nd law

| non-linear linear (modern)

|

The triumph of the good god over the evil god to create the order of the cosmos and society would then represent the pre-eminence of non-linear over linear dissipation. If myth should represent correctly the thermodynamics of order-formation without confusion, then it'd have: an evil god (the second law: entropy-increase) operating on the material of the (supreme) good god (conserved amount of the already inhomogeneous total: the first law) and creating order while trying to dissolve the inhomogeneity -- until, of course, the inhomogeneity runs out. Note that in modern science the initial inhomogeneity (e.g. the local concentration of energy in the form of stars) whose dissolution results in macroscopic order is the work of gravity and not thermodynamics. But the dissolution of the sun is experienced as the divine, conserved substratum of being (of energy) flowing in from its local concentration. Thus the kingship of the cosmological empire of the Near East is conceived of as directing this flowing into the cosmo-social organism. This dissolution of the divine (in fact of its local concentration) can then be symbolized as the sacrifice of the original good god. Hence Pangu (and countless other myths of cosmogony through the sacrifices of the primeval gods and ancestors). When the flow runs out -- when the local concentration disperses, reaches equilibrium with the surrounding -- then local concentration would have to be re-created -- the rewinding of the system -- in order to keep the order continuing: thus periodic sacrifice of the good god (sacrifice as the restaurant of the cosmos) or some other cosmogonic rituals to maintain the cosmo-social order (Eliade's "myth of the eternal return" or "regeneration of time"). But a more simple representation would have a god operating on the material of another god to create order while dissolving it -- here the dissolving operation of the god represents the energy-flow from the local concentration and its creative (non-linear entropic) consequence despite its dissolutive goal: the triumph of the non-linear entropic within the general linear entropic operation of the thermodynamic nature. Here we have another mythic genre, not of the self-sacrifice of a good god, but of a good god (non-linear) defeating a chaotic (equilibrium) bad god, dismembering it (differentiating it away from equilibrium), and thus creating order: the ennuma elish type. Of course the order would "run out" because of the more common linear entropic increase and so the whole scenario has to be repeated periodically (during the New Year). "Dans une zone géographique considérable et à partir d'un certain moment historique, la cosmogonie (comme, d'ailleurs, toutes les autres formes de 'création' et de 'fondation') comportait le combat victorieux d'un dieu ou d'un Héros mythique contre un monstre marin ou un dragon (c.f. par exemple, Indra-Vritra, Baal-Yam, Zeus-Typhon, etc.). On a pu montrer qu'un scénario analogue existait chez les Indiens védiques et dans l'Iran ancien, bien que dans ce dernier cas les sources soient tardives et présentent le mythe fortement historicisé. En effet, le combat du héros Thraetona contre le dragon Azi Dahaka auquel fait allusion l'Avesta (Yashts 9: 145; 5: 34; 19: 92 sq.) est raconté par Firdousi comme la lutte du roi Faridun (-Frêtôn -Thraetona) contre un usurpateur étranger, le dragon Azdahak... Or, les traditions tardives précisent que c'est au jour du Nouvel An que le roi aurait vaincu Azdahak." (Eliade, p. 334; "In a considerable geographic zone and starting from a certain historical moment, cosmogony (like, elsewhere, all other forms of 'creation' and 'foundation') involves the victorious combat of one god or mythical hero against a marine monster or a dragon [for example, Indra-Vritra, Baal-Yam, Zeus-Typhon, etc.]. One could show that an analogous scenario existed among the Vedic Indians and in ancient Iran, although in this latter case the sources are late and present a heavily historicized myth. In effect, the combat of the hero Thraetona against the dragon Azi Dahaka to which Avesta makes allusions... is recounted by Ferdowsi as the battle of the king Faridun... against a usurpating stranger, the dragon Azdahak... Now, the later traditions specify that it is on the day of the New Year that the king had defeated Azdahak.") Later, in "The Gender Aspects of the Origin of Human Religiosity", we will see how we may adopt Chris Knight's theory (ibid.) and posit the origin of the theme of the dragon together with the origin of human rituals in women's "sex strike" and the origin of the theme of "the dragon-slaying male hero" in a male counter-revolution against this ritual of women's. To return to our topic, the good god thus in fact also incorporates evil as part of itself (non-linearity is still entropy-increase, the general evil). Whatever the type, something (in reality, the sun) has to be dispersed, Pangu or Tiamat, in order for order to arise. We will cover all the different manifestations of the two types later on.3

But it must be mentioned here that this type of myth, symbolizing the triumph of non-linear over linear entropy-increase through a theomachia, at its primitive stage is frequently of the reverse formulation to its advanced stage such as the monotheistic Zoroastrianism. For example, among the Huron, the primordial god is Aataentsik, the mother of all beings and usually identified with the moon, who is the primordial god but also the evil god: in this sense she is the equivalent of Tiamat and the Egyptian Nun, the original gods of chaos. In all these symbolizations of the primitive stage (Mesopotamian or Huron) the conserved substrate of all being is identified as evil, the natural equilibrium state, so that the primordial god is compacted of linear entropy and the first law. The good god of Huron is Iouskeha, grandson of Aataentsik and identified with the sun, who "had charge of the living. It was he who made the world a suitable place for human beings. He created lakes and rivers by freeing the waters that hitherto had been confined under the armpit of a supranatural frog [thus making order out of chaos]. He also had released the animals from a great cave in which they had been concealed and had maimed each species in one leg so that they could be hunted more easily. The exception to this was the wolf, which he missed, and which remains hard to catch to this day. Iousekeha also made the corn grow and provided good weather. He had learned the secret of making fire from the great turtle, who was his ancestor, and had passed this knowledge on to human beings. As a patron spirit of warfare and prisoner sacrifice, he also maintained the vital forces of the natural cycle on which human beings depended [i.e. maintained the stability of the order of the cosmos against its tendency to reach equilibrium]." But "Aataentsik spent her time trying to undo the good works that Iouskeha had done [i.e. she was the force of equilibrium, of linear entropy, inherent in the conserved substrate]. It was she who made human beings die. Aataentsik spread epidemics among the Huron and their neighbors and had charge of the souls of the dead [i.e. she was the conserved substrate of being to which the souls return]." Later on, however, Aataentsik was pregnant with both Iouskeha and Atawiskaron, the good and the evil god! Thus instead of the Iranian case of an ultimate good god begetting the secondary good and evil gods, here the ultimate evil god produced the secondary evil and good gods. "Iouskeha was born in the normal fashion, but Atawiskaron aggressively cut his way out of his mother's womb, killing her in the process. Atawiskaron had inherited many of Aataentsik's malevolent qualities and spent much of his time trying to undo the good works his brother had performed for human beings. Eventually the two brothers engaged in mutual combat. Atawiskaron fought with the fruits of a wild rosebush and Iouskeha with the horns of a stag. Iouskeha struck his brother so hard that the blood flowed. As he fled, the drops of his blood fell on the ground and were turned into flint (atawiskara), which the Indians later used to make stone tools and weapons." (Bruce Trigger, Huron, 2nd ed., p. 108 -9) The representation here is thus: Aataentsik = conservation; Iouskeha = non-linear entropy-increase; Atawiskaron = linear entropy-increase. In other words, at the primitive stage of the symbolization of order-disorder -- which becomes a thermodynamic problem in modern physics -- the state of conservation could be experienced as bad as well, the ultimate quantitative equilibrium confused with the ultimate qualitative equilibrium (i.e. chaos: below), but through differentiation it later could then become the ultimate good.

G. Justice, karma, or karmic thinking, and "guilt" in the general sense. Justice, just like divinity, immortality, creation-foundation myth (order-formation), and sacrifice, was a reflection of the anamnesis of thermodynamics. Justice came from the experience or memory of equilibrium, confused, again, with conservation. That is: equilibrium exists differently in the two laws, and differently even within the second law: it is the overall, general, final quantitative state in the first law, where eventually all apparent changes result in no substantial change, but only in quantitative sameness or equilibrium (Conservation). In the second law equilibrium can mean the final, inevitable goal (and so the first cause) of everything, the inescapable leveling of all meaningful order, of all differences, down to meaningless disorder, to sameness, which is qualitative equilibrium. Or it can mean, in a restrictive sense, the maintenance of order by taking in energy and disposing of waste as disorder (the self-maintenance of an open dissipative structure): the maintenance of an ordered system (restrictive or internal equilibrium qualitatively) far from (qualitative final or external) equilibrium. Thus the meaning of equilibrium exists on a scale from the most restrictive to the most general: the maintenance of order - the sameness of disorder - the ultimate sameness of amount (Conservation).

In such undifferentiated consciousness as the cosmological form, the tribal, or contemporary laymen the three types of equilibrium are not distinguished. Justice, the righting of wrongs, the most primordial experience of which is captured in the formula "an eye for an eye", is typically conceived of as the necessary or even automatic consequence of the state affairs, as if part of nature. This is conditioned by our experience of thermodynamics, but in all different ways. "An eye for an eye" in terms of quantitative equilibrium (first law): We can understand the primary motivating experience of justice by thinking about a chemist doing equations for chemical changes or physicists doing equations: the two sides of the temporal chain of "transformation" (from the side of atomic compositions to be transformed to the side of atomic compositions transformed into) must remain the same because of the first law, Conservation (no atoms should be lost during the chemical transformation). In fact this is why they are called "equations". Justice as the righting of wrongs is basically an "equation": the advantage ("pleasures") gained from injuries done at the beginning of the temporal chain of events must be balanced by an inversely equivalent disadvantage ("displeasure") derived from injuries suffered at the end so that the total amount of pleasure-pain of the doer remains the same in the end. Such consciousness of justice based on necessary conservation not only made intelligible tribal feud but also ordinary person's demand of "justice" when being done wrong by criminals in contemporary society. In tribal feud, one tribe robbed the other, and this other deemed it necessary to rob back, to exact revenge, in order to restore justice, that is to say to even out the imbalance between advantage and disadvantage (pain and pleasure) and to return to the equilibrium disrupted by the dis-equilibrium (in-equation between the two ends) caused by the first tribe's robbing out of the blue. Today the mother of a murdered victim demands execution of the murderer as a matter of justice also in order to return to the state of equilibrium/ equation temporarily disrupted by the murderer's act of causing harm to the victim's family without the victim's family doing anything to incite it.

In The Genealogy of Morals from which this view of the origin of justice is originally derived Nietzsche says that the origin of punishment lay not in the idea that the wrong-doer should be held responsible for his acts (or even that only the guilty should be punished),4 but in the idea that, as anger at being injured causes one to want to vent on the person who caused it, "this anger is held in check and modified by the idea that every injury has its equivalent and can actually be paid back, even if only through the pain of the culprit", and this idea eventually came from the "contractual relationship between creditor and debtor, which... points back to the fundamental form of buying, selling, barter, trade, and traffic." (trans. Kaufmann, p. 63) When someone does us harm and gains advantage (pleasure) from it, s/he owes us a "debt" -- a portion is taken out of my store of pleasure and given to him or her and s/he thus has an excess amount of it in his or her store. Thus the conservation (first law) of the amount of pain-pleasure can be imagined diachronically across the time-span of a single person or the (final) equilibrium (second law) of it can be imagined synchronically across persons. Nietzsche then concludes that punishment -- the means by which we restore justice or equilibrium -- is a form of compensation, and, as physical punishment as it often is in the justice system (e.g. execution, imprisonment, bodily disfigurement), is "a recompense in the form of a kind of pleasure -- the pleasure of being allowed to vent [one's] power freely upon [another] who is powerless", or the pleasure of being master over someone else (p. 64- 65). That is, precisely the pleasure gained from doing injuries back to the person. But if justice and punishment as the means for it thus originated in the first economic exchange system of the primitive people, I would simply argue that the economic exchange, and in fact all forms of exchange, together with justice, originated in the intuition of the thermodynamic structure of the Universe. Because of this structure, transformations should never involve loss, or inequality (disequilibrium of a system) should always be evened out in the end; a person who has suffered injury should always have the injury paid back, even if only in the form of pleasure over the equivalent injury of the injuring person, and a person who has caused injury should always suffer in the same amount as the pleasure he gained while causing the injury. The total amount should always be conserved: no net gain or loss of pain or pleasure.5

This justice, which uses punishment as means of its restoration, thus means the equilibrium, quantitative (diachronically: in terms of the first law) or qualitative (synchronically: in terms of the second law), necessarily conserved or always reached in the end, respectively; but undifferentiated consciousness does not distinguish the three types of equilibrium, as order to be maintained, as disorder (leveling of differences) or as Conservation. Insofar as Conservation is simply a guaranteed state of the universe, man often thinks that justice, as restoration of equilibrium or as conservation of the net amount of pleasure and pain, is also always automatically guaranteed, hence the idea of "karma", that a person will at some time in the future, even in the next life, get what he or she deserves simply as a matter of fate so that the net amount of the pleasure or pain experienced will in the end be conserved.6 Thus the prevalent saying in classical Greece of which the sophists became sceptical but which Plato had had to defend was: alla gar en Aidou dikhn dwsomen wn an enqade adikhswmen, h autoi h paideV paidwn. "For however in the Hades will we pay [lit. give justice] for what injustice we have here committed, either we ourselves or through the children of our children." (Republic, Book II, 366 a5) Dike is the natural getting-even of, or compensation for, adike, through either the misfortunes of the same person or those of his descendents. The "karmic thinking" is thus universal across all peoples, and only explicitly named "karma" in India; and it frequently takes the mythic form of the "judgment of the dead": the soul after death and going to the spirit world would first get a trial there apportioning reward (pleasure) or punishment (suffering) in order to even out any disequilibrium of pain-pleasure the soul has incurred while embodied, and only after the restoration to equilibrium would it be allowed to reincarnate. This karmic thinking can again be compared with the "retribution of nature" in the structural perspective with respect to the production of virtual particles through quantum fluctuation: just as Nature will eventually take back the particle given out for free after the apportioned time, so here, in the functional perspective, it will even out the pleasure one has gained through evil done with the displeasure resulting from evil suffered. But when justice is applied system-wide to the whole of society it is experienced as order, the maintenance of the internal equilibrium or stability of an ordered system away from external equilibrium. In this case of the collective we know that in order to maintain social justice we have to work for it, i.e. pump energy into it.

Through this discussion of justice we can arrive at an understanding, based on the first law of thermodynamics, of the feeling of guilt in the general sense. When we injure someone (which is a gain of pleasure or satisfaction), our understanding that the net amount of pleasure/ pain should be conserved leads us to fear that "retribution" will eventually happen to even out the pleasure just gained. The fear for this natural retribution is the fear for its unpredictability in timing and form. Atonement or repentance through self-inflicted suffering, e.g. self-mortification or extreme austerity, is our voluntary effort at restoration of the net amount of pleasure/ pain just as in the case of sacrifice. (Hence the Christian penitent, filled with the feeling of guilt ["sin"] and fearing for retribution: so the more he torments himself, the safer he feels.) Repentance is preferred because here we have control of the timing and form of the necessary retribution. People especially today who have no feeling of guilt (or rather the fear and anxiety associated with it) are well enough differentiated in their consciousness to know that it is not these functional entities (person's pleasure and pain) that are conserved necessarily but only the impersonal atoms and energy that have nothing to do with the psychological dynamics of human beings. Thus during the time of great differentiation of mind both Buddha and Plato had had to encounter sceptics who no longer believed in karma or in natural retribution for their bad deeds. Today the educated individuals who do not believe in karma (like the straight-thinking psychologist just cited) usually observe justice only out of respect, sympathy, and integrity and no longer out of fear, because they understand that justice and the guilty feeling associated with repentance for wrong doings (and sometimes with sacrifice) all arise from the incorrect application of the law of Conservation to functional entities (such as pain, pleasure, satisfaction, etc.) rather than, correctly, to the level of structure.

The repayment of debt through repentance could then be manipulated by reversing its process. A person might intentionally inflict suffering to himself in order to secure good fortune for later. In artificially creating for himself disadvantages (suffering), the self-mortifier was waiting for the natural "retribution" (in this case, advantages, pleasures) that would necessarily come to even out the disadvantages already suffered. This is the Christian penitent in reverse. This is just like the attempt of an influence-wielding man in a primitive tribe to give out as much gifts as possible or to hold as many public feasts as possible -- even to the point of almost bankrupting himself -- in order to "cause" among his fellow tribemen indebtedness to him, in the name of which he may then in the future direct the actions of these others who thus need to satisfy his desire in order to "repay" him.7 Self-mortification through the denial of especially sensual pleasures (e.g. sex) can gradually pass into a different connotation of "purification", i.e. concentration of the soul away from equilibrium, which now becomes the requirement for "soul-power".

A therapist of contemporary time may lament over human beings' insistence on justice as a source of misery. He may tell the story of a dog which waits outside the restaurant everyday on account of the restaurant's policy of throwing out the bones every night after closing. If one day the bones stop being thrown out the dog, disappointed, will simply go to the next restaurant. Humans, however, in such circumstance will waste energy protesting even if the effort will turn out futile, because they want "justice." Why can't people be more practical like animals, saving themselves so much trouble and misery? Human beings' seemingly irrational hard effort in clinging to ideals such as justice as opposed to an easy-going life of animals that comes with utilitarianism is probably rooted in the fact that human beings have always already intuited the thermodynamic laws whereas animals do not. The hordes of deer that are hunted by the same hordes of lions everyday probably never develop the feeling that the lions are unjust "oppressors" and that one day revenge (pay-back) should be exacted upon these carnivores or that their oppression should be canceled through a "revolution". Animals do not think about the thermodynamics of equilibrium and conservation.

In the cosmological civilizations it is justice at the collective level that is at issue. In the cosmological empire, the king, with the divine force (that flux of energy of divine atmospheric substratum) acting or mediating through him, was responsible for the maintenance of justice/ order in society, the good rewarded and the bad punished (giving back to the givers and taking away from the takers in order to conserve the net amount for each person: justice at the personal level) so as to maintain social equilibrium. In this way "justice" and the like were often associated with his title (e.g. the Archaemenian kings). The maintenance of the internal order (justice) of the social organism with the energy of the divine anima meant then somehow that the failed conservation of pain-pleasure complex of the persons -- even in the temporal, social world, i.e. before the karmic mechanism of the natural, cosmic world set in -- signified the relapse of society into injustice, into chaos, into equilibrium with the external environment (disorder), just as the same failed conservation on the cosmic level (as when Zarathustra complained to the supreme god: "Why haven't thou yet punished the evil-doers?") pointed to the breakdown of the cosmic structure, of the "laws of nature" in today's scientific jargon which at the time of functional perspective actually comprehended human pleasure, pain, and fate. The maintenance of social justice was furthermore associated with the king's performance of rituals at particular intervals of time to restore the cosmo-empire to its original pristine state (order; e.g. the New Year Festivals in Mesopotamian empires). The king maintained justice for each and the internal equilibrium-stability of the autopoiesis of the social organism (order) through transferring the divine, cosmic substance (the conserved substrate as energy) to the social realm and through maintaining a relationship of equilibrium with the gods or ancestors or the cosmos (e.g. Heaven) to pre-empt any possible "retribution by Nature". Thus was the king "just", maintaining "justice".

H. Periodicity as the defining characteristic of "intraworld" religions which the disengagement of salvation would break up. Another reason for which primitive religions are characterized as pre-salvational is that there the permanent resolution of the tension between the two laws of thermodynamics was never really sought after: the tension between on the one hand life (and society) as a mere open dissipative structure -- i.e. a temporary, localized, limited order maintained at a continually generated debt of order destroyed -- and then death or the disintegration of its order necessitated by the passage of time (the second law), and on the other the fact of Conservation despite all disintegration or constitution of order (the first law). That is, the problem of order at the expense of (greater) disorder and yet some sort of Conservation despite the dissolution that is the function of this necessary greater and greater disorder.

As said, consciousness has always already intuited the most fundamental laws of nature, the first and second law of thermodynamics. Naturally, consciousness has also experienced the conflicting tension between the two laws, the destructiveness of time on the one hand (the second law), and the preservative conservation on the other (the first); or the separateness of beings (the second law) as opposed to the consubstantiality in Being (the first); or again, the temporal passing-away versus the eternal, conservational sameness. The experience of this tension produced in consciousness a fundamental dichotomy between the temporal and the eternal -- between disparate beings and Being as the source for all beings -- and so a fundamental anxiety for the relation between the two poles, a fundamental search for the resolution between the mortal state and immortality. Furthermore, as said, the non-distinction between Conservation and the internal equilibrium of an ordered system stabilized away from the general (external) equilibrium also generates the categories of good (order) and evil (dissolution of order through entropy-increase) that overlap that opposition between mortality and immortality. The tension between the experiences of the two laws of thermodynamics -- but not yet its resolution -- is the principal theme of the cosmological myth, and the germ from which springs the history of human search for salvation, which can be defined as the permanent resolution of the tension at long last.

But its non-resolution in "intraworld" religions is what produces their character of "periodicity" (the myth of the eternal return). In the cosmological civilizations, for example, the king, in transferring the divine conservedness into the social internal, hoped to "fix" or conserve the internal equilibrium or stability of the order of the imperial organism against the disintegrating effects of the second law -- constantly feeding it -- thus he maintained justice, offered restorative sacrifice (or expiatory: depending on whether the restoration was based on the imagery of regeneration or that of purification, that is, that of "washing away" the stains of disorder), and replayed the cosmogonic (order-generative) theo-machia between the good and evil gods during the New Year. Among the Australian aborigines, the Arunta also annually re-enact the cosmogonic acts of the ancestors during the ritual of intichiuma. All these were acts of "feeding": pumping into society or the cosmos (divine) energy to maintain its order against disintegration, because the divine substratum of being is energy, just as the substratum of all matter today in the scientific perspective is energy. The undifferentiation between quantitative equilibrium (Conservation) and qualitative equilibrium of the restricted sense (stability of order maintained through being positioned at the midpoint within the energy gradient) meant that the resolution of the tension between the two laws of thermodynamics through the negation of the second law with the first would result in the thinking that everything not only was conserved in terms of its "amount" after its entropic dissolution but that its order -- so the hope went -- could be so conserved as well. One could thus envisage the possibility of negating the entropic disintegrating effects of the second law altogether and once and for all through a "feeding" of the divine restaurant once and for all after which one would never need a feeding again to regenerate against the otherwise necessary entropic disintegration (e.g. the Gospel of John): the eternal conservedness of perfect order never to degenerate. The search for such permanent resolution is what is called (in this case, first mode or eschatological) salvation, and properly so called because the resolution typically consists in the negation of the second law (always greater disorder) by the first law (eternally unchanging, undegenerating, conservation of some sort of ultimate order), i.e. negation or dismissal of the temporal, meaningless coming-into-being-and-then-passing-away through the Eternal Unchanging. This search for resolution, usually by means of negation, really started when philosophy and testamental religions were differentiated out of the compact cosmological myth.

The non-resolution between the first and the second law of thermodynamics in the cosmological civilizations results in the essential mode of existence proper to these civilizations as maintenance of order. We have said that the New Year Festival of the Mesopotamian empires is the clearest expression of (the attempt to deal with) the experience of the second law: humans learn of the second law by observing that a house just built (an order created), if not fixed periodically (maintenance as pumping energy into it periodically), will decay into shabby form; that their body (an order), if they do not eat periodically (maintenance, pumping energy into it), will disintegrate. Primitive humans have always known that entropy (the amount of disorder in the universe) necessarily increases with time and that order can only be stabilized against the entropic increase of Time through the constant or periodic restorative energy-input. The cosmos therefore needs periodic "fixing" or restoration (maintenance) lest it degenerate, i.e. the rituals of the New Year Festival. This most explicit ritual expression of the understanding of thermodynamics is also brought out in the same way by the Iranian version of the New Year, the Nourouz (lit. in modern Farsi, "New Day"), which, "comme tout scénario rituel du Nouvel An, renouvelait le Monde par la répétition symbolique de la cosmogonie [the triumph of the king over Azdahak as already mentioned]." (Eliade, ibid., p. 334) The Iranian Nourouz illustrates most clearly how restorative religious rituals, those that effectuate "la reprise du Temps à son commencement", or the restoration of the primordial, sacred, pure Time, are about the temporary negation of entropy and the arrow of time as determined by the second law of thermodynamics. During the ceremony of Nourouz "the king proclaims, 'Now is a new day of a new month of a new year: we must renew what Time has used up.' Time has used up human beings, society, and the cosmos [obviously because order tends to dissolve as time passes: the second law], and this destructive Time was the profane Time, the duration [la durée] properly speaking: we must abolish it... [to re-bathe] in the pure, strong, and sacred Time." (Le sacré et le profane, p. 68 - 9) Time is destructive because of the second law; it is because entropy always increases with time that one's room always gets messier and messier, and never more and more orderly by itself -- until one day one has to clean it up and return it to its former "pristine state" -- just as eating returns one's body to its former pristine state -- that's the mythic moment, the "pure, sacred Time". A good analogy, because, first of all, even today Iranians have the custom of total house-cleaning during the Nourouz; and second of all, because, as Eliade notes further, the passing-away of the old world and the birth of the new during the new year means also "an annulment of the sins of the individuals and of the community in its entirety, and not a simple 'purification'" (ibid., p. 68): a total soul-cleansing.

"La conception était familière aux Indo-Iraniens; cependant il est probable que, sous les Archéménides, le scénario avait également subi des influences mésopotamiennes. De toute manière, la fête du Nouvel An se déroulait sous l'égide d'Ahura Mazda [the ultimate conservative force, and the energy substratum of all being, all confused with the original inhomogeneity and the subsequent non-linear entropy-increase creating order while dissolving this inhomogeneity], hiératiquement représenté sur plusieurs portes à Persépolis... [Thus] le Roi iranien était responsable de la conservation et de la régénération du Monde, autrement dit, que sur le plan qui lui était propre, il [either as the influx of the energy of the divine conserved substrate of being or as the non-linear entropic operation] combattait les forces du mal et de la mort [i.e. forces of the linear entropy-increase], et contribuait au triomphe de la vie, de la fécondité et du Bien [the consequences of the divine influx and non-linear entropy]." (Eliade, Histoire des Croyances, p. 334) The king doing his job, as the maintenance personnel for the order of the cosmos (in his role as the initiator in the New Year rituals) and as the maintenance personnel for the social order (in his role of maintaining law and order, justice, the internal equilibrium of the social organism), is constantly busy pumping energy into society and the cosmos by transferring the divine substance of order (ultimate quantitative equilibrium or eternal conservedness which is energy) into both (as if "feeding" the cosmos and social organism) in order to thus defeat or check the forces of disorder (linear entropy) -- with justice-law, theo-machia, and sacrifice -- and this is his role as the mediator between heaven and earth. This constitutes a failure in the resolution between the first and the second law, because such recognition would enable him to envisage the possibility of restoration once and for all instead of periodically. And this resolution itself is finally based on the non-understanding by the immature consciousness of the difference between quantitative equilibrium (Conservation) and qualitative equilibrium or stability of order (maintained through being positioned at the midpoint within the energy gradient) so that Conservation (quantitative) could somewhat mistakenly be taken as also conservation of (qualitative) order.

The constancy of maintenance of order (of the cosmos and of the human social) is reflective of the essentially non-historical mode of the tribal organizations and the cosmological civilizations, their existence in undifferentiated time, the present of order as the stand-still moment to be maintained: ""Es [Gegenwaertigen] gegenwaertigt um der Gegenwart willen" ("The presencing is be-ing present for the sake of the present") to use Heidegger's description of the same phenomenon on the ontogenic level of the person's life (c.f. later). From the Israelite Yahweh religiousness is to emerge eschatology as the restoration once-and-for-all, like "eating once and for all and never having to eat again." This is historical form, and properly salvational, and corresponds to Heidegger's "Entschlossenheit" (resoluteness) on the ontogenic level, as we shall see.

The maintenance of order through periodic refuelling (ritual) is also expressed in the aspect of the restoration of the "right way" of doing things:

| Au niveau des civilisations "primitives", tout ce que l'homme fait a son modèle trans-humain; même en dehors du Temps "festif", ses gestes imitent les modèles exemplaires fixés par les dieux et les Ancêtres mythiques. Mais cette imitation risque de devenir de moins en moins correcte [because of the arrow of time!]; le modèle risque d'être défiguré ou même oublié. Les réactualisations périodiques des gestes divins, les fêtes religieuses, sont là pour réapprendre aux humains la sacralité des modèles. La réparation rituelle des barques ou la culture rituelle du yam [speaking of the rituals during the annual festivals on the Polynesian island of Tikopia] ne ressemblent plus aux opérations similaires effectuées en dehors des intervalles sacrés. Elles sont plus exactes, plus proches des modèles divins, et d'autre part elles sont rituelles: leur intention est religieuse. On répare cérémoniellement une barque non pas parce qu'elle a besoin d'être réparée, mais parce que, dans l'époque mythique, les dieux ont montré aux hommes comment on répare les barques. Il ne s'agit plus d'une opération empirique, mais d'un acte religieux, d'une imitatio dei. L'objet de la réparation n'est plus un des multiples objets qui constituent la classe des "barques," mais un archétype mythique: la barque même que les dieux ont manipulée "in illo tempore"... (Le sacré et le profane, p. 75 - 6.) |

Getting away from Eliade's rather metaphysical interpretation of the primitive experience of temporality, our more ordinary thermodynamic interpretation would not see the division between the divine, archetypal way of doing any thing and its empirical, human variants, but only the degeneration through time of the divine, pure way into the human, impure ways. Hence the need to restore periodically the divine way.

I. Concluding remarks. One may wonder of course why the ancients did not understand that energy (divine substance) was automatically pouring in from the sun to regenerate the biosphere every day and that humans really had no need to pump energy into the cosmos themselves. The answer is two-fold, already hinted at. First the automatic restoration of the Earth (the whole cosmos for the primitives) by Nature (the rise of the sun every morning) applies only to its biospheric component and not to human society, whose maintenance depends on human effort. But the primitives did not know this, because they experienced society compactly as a microcosmic outgrowth of the cosmos itself; and since society clearly did disintegrate even if the sun rose every day, they were apparently quite justified in believing also that the human effort spent on maintaining social order was compacted with the Nature's own automatic forces of regeneration -- thus that sacrificial restoration and the natural restoration by sun-rise for example were just two sides of the same operation. Primitive humans were thus experiencing themselves as participating in the cosmic (natural) chain of causation itself when they sacrificed. Today we don't offer "sacrifice" to keep nature-society running because we have differentiated between the two and (correctly) understood that the order of society does not depend on the order (laws) of nature. Secondly, those aspects of Nature that could disrupt human social order (natural disasters) but which were really just part of Nature's self-working and so were as "valid" as were those other aspects that did not so disrupt (e.g. good weather) were experienced as however the disintegrations of the nature-cosmos due to the compact experience of the human and the cosmic order as an integrated whole: if the cosmos still ran down despite sun-rise everyday, then the automatic input of energy by the sun must either be irrelevant or at least insufficient, and it was up to the humans themselves to feed the cosmos and stabilize its order away from equilibrium. Underlying the restorative religiousness was therefore the egocentric view of the primitives that saw their own social order as the reference point by which to define what was right (order) and what was wrong (disorder) everywhere else.

Human religiousness is therefore fundamentally a thermodynamic problem. Because entropy always increases (the second law), order is not free, but actually requires the destruction of some other order so as to be (in fact the destruction of order has to outweigh the creation of it):8 the sun has to gradually but continuously destroy itself -- waste itself away -- through the nuclear fusion reaction within itself so that the biospheric order on earth may appear, feeding on the energy thus released from the "sacrifice" of the sun.9 Animals have to be killed and eaten so that energy may be released from them to sustain the order of our body. As said, this is part of our primordial sin: our order itself depends on the destruction of more order, by virtue of our constitution as open dissipative structures -- by virtue of the very thermodynamic structure of the cosmos itself. The order of our body incurs for us a debt that we can never finish paying off: we have to kill, consume, and then defecate as long as we live. Thus sacrifice of the primordial god has to happen in order for social order to be founded (the "creative" function of sacrifice) -- and this sacrifice has to be periodically repeated to guard the social order against reaching equilibrium with the disordered environment (the "restorative" function of sacrifice). Or the non-linearity has to outweigh the linearity of entropy production -- and continually so -- in order for cosmo-social order to appear -- and to continually be maintained. Or the king has to constantly be directing the flow from the concentration of the divine conserved substratum of being (as one does the energy from the sun: the energy released from the divine sacrifice) into the cosmo-society in order to stabilize its order away from equilibrium. The cosmological civilization, ordered around the cosmological myth, and maintaining its order with rituals based on this myth, demonstrates and is engaged in a mythic understanding of thermodynamics.

Postscript: A Hopi myth of the beginning will illustrate this thermodynamic dilemma at the center of human religiosity as well as the topic of next chapter, the origin of the sacred, that the "sacred" originally not only means the atmosphere but also "food" (plants and animals) that is taken to be the concrete manifestation of the atmosphere:

|

During the time when Kloskurbeh, the creator, lived on this earth, humans did not yet exist. But one day, when the sun was high above in the sky, a young man came therefrom, who addressed the creator thusly: "Uncle, the brother of my mother." [Traces of cross-cousin marriage here.] This young man had been born from the foam of waves, the foam which the wind had animated (!) and the sun heated. It was the movement of the wind, the humidity of water, and the heat of the sun which had given him life... Especially the heat, because it was life itself. The young man therefore lived with Kloskurbeh and he became his principal assistant.

Then, one day, after these two powerful beings had created all sorts of things, there came to them, when the sun shined right at the zenith, a very pretty young girl. She was born from the marvelous plant which the earth had produced, from dew, and from heat. A dewdrop fallen on the leaf had been heated by the sun, the sun which warmed up all and gave life. The young girl was thus born, from the green and living plant, from dew, and from heat. "I am love," said the young girl. "I will make you strong, I am the Nourisher, I provide nourishment to all humans and animals. I am loved by all." Kloskurbeh thus thanked the Great Mystery Above for sending them this young girl. The young man, the Great Nephew, married the girl, and she became the Primordial Mother. Kloskurbeh, the Great Uncle, who taught them all that they needed to know, taught their children how to survive. He then left for the North, from where he would return if anyone should need him. After that, men proliferated. They lived by hunting, and the more they hunted, the more numerous they became and the less game they found. Too much hunting had resulted in the disappearance of game animals. Famine thus befell on them. The Primordial Mother was quite troubled by this. Small children came to her and said, "We are hungry. Give us something to eat." But, having nothing to give to them, she started crying. She said to them: "Be patient. I'm going to make some food to fill your stomach." But she continued to cry. Her husband then asked her, "How can I see you smile again? What can I do to make you happy again?" "There is only one thing which can stop my tears." "What?" "Kill me." "Never will I be able to do such a thing!" "You must. Otherwise I'll never stop crying or lamenting." Her husband then went to the end of the earth. He came to the North to ask the Grand Master, his uncle Kloskurbeh, what he should do. "Do what she asked of you. You must kill her," said Kloskurbeh. The young man thus returned and started crying for his turn. But the Primordial Mother said, "It shall be tomorrow when the sun is at its zenith. When you have killed me, tell two of your sons to take me by the hair and drag my body to the end of the earth, until my flesh should become completely separated from my body. Then, you shall collect my bones and bury them in the middle of the forest. Then you shall go away." And she smiled: "Wait until the seven moons have passed, and then come back. You will find my flesh, which I have given by love, and which will nourish and keep all of you strong until the end of time." [The primordial meaning of the "sacred", as we shall see.] Thus was done... They dragged her corpse here and there until the earth was covered with her flesh... and buried her bones... When the husband, his children, and the children of his children came back to this place after the seventh moon had passed, they saw that from the earth now had sprung up all these green plants... whose fruit, the maize, was the flesh of the Primordial Mother. This was her gift to her children so that they might survive and prosper. They thus divided the flesh of the Primordial Mother and found it sweeter than words could describe. Thus her flesh and her spirit renewed themselves every seven months, generation after generation. And from the place where they have burned the bones of the Primordial Mother sprout forth a different plant, with large and perfumed leaves. This was the breath (spirit, soul) of the Primordial Mother, and they heard it telling them: "Burn these leaves and smoke them. This plant is sacred. It will clear up your spirit, facilitate your prayers and revigorate your heart." Thus the husband of the Primordial Mother called the first plant skarmunal (maize), and the second, utarmur-wayeh (tobacco). "Remember," he said to his children, "to take great care of the flesh of the Primordial Mother, because it is her goodness which is transformed into substance. Take great care of her breath, because it is her love which is transformed into tobacco smoke. Remember her and think of her every time you eat and smoke, because she has given up her life so that you can all live. She is not dead, however; she lives always; by giving her eternal love, she renews herself ever and ever." |

Thus Eliade makes the general conclusion (for elsewhere but applicable here as well): "According to the myths of the first horticulturalists of tropical regions, the edible plant is not given in nature; it is the product of a primordial sacrifice. In the mythic epoch, a semi-divine being, male or female, is sacrificed so that tubers and trees with fruits can grow from his or her body." (Cited by René Bureau, "Esquisse d'une théorie sociologique du sacrifice", in Mort pour nos péchés, 3eme ed., publications des Facultés universitaires Saint-Louis, Bruxelles, p. 97; "Suivant les mythes des premiers horticulteurs des régions tropicales, la plante comestible n'est pas donnée dans la nature; elle est le produit d'un sacrifice primordiale. A l'époque mythique, un être à demi divin, masculine ou féminin, est sacrifié pour que les tubercules et les arbres fruitiers puissant croître à partir de son corps.") Hence "it is attested in numerous regions that in the beginning of the spring season, one or more victims, often a young girl, were put to death." ("Il est attesté dans de nombreuses régions qu'au début de la saison printanière, une ou plusieurs victimes, souvent une jeune fille, étaient mises à mort." Ibid.) After a while the sacred energy released by the primordial ancestress is used up; in order for the earth to keep producing the crops, the energy-releasing sacrifice of the ancestress must be repeated periodically, especially before the growth season. Hence a human girl is sacrificed in imitation of the ancestress.

Footnotes:

1. Mircea Eliade posits the origin of this "primordial human experience of spatiality" in "hominisation", i.e. upright posture, walking on two legs, which the hominid lineage developed after its separation from that of the great ape leading to chimpanzees. "On ne peut se maintenir debout qu'en état de veille. C'est grâce à la position verticale que l'espace est organisé en une structure inaccessible aux pré-hominiens: en quatre directions horizontales projetées à partir d'un axe central 'haut'-'bas'. [C.f. the Chinese six he (六和): up, down, north, south, east, and west: the three-dimensional space.] En d'autres termes, l'espace se laisse organiser autour du corps humain, comme s'étendant devant, derrière, à droite, à gauche, en haut et en bas. C'est à partir de cette expérience originaire -- se sentir 'jeté' au milieu d'une étendue, apparemment illimitée, inconnue, menaçante -- que s'élaborent les différents moyens d'orientatio; car on ne peut vivre longtemps dans le vertige provoqué par la dés-orientation. Cette expérience de l'espace orienté autour d'un 'centre' explique l'importance des divisions et répartitions exemplaires des territoires, des agglomérations et des habitations, et leur symbolisme cosmologique." (Histoire des croyances et des idées religieuses, vol.1, p. 13) Eliade of course does not take into account the temporal component of this primordial human experience of the lived world (or rather the "participation in the cosmos"), and Voegelin does not include the up-down axis in the preceding. But together this vertical posture results in the explicit consciousness of the four dimensional reality -- crawling on four legs of course can also lead to awareness of the up-down axis, but less explicitly -- which the cosmological symbolism inherits from the tribal. But the origin of this four dimensional reality in human experience is not yet exhausted at this point, but only by Heidegger's analysis of Weltlichkeit later.

2. Except that the political categories associated with it (e.g. king, empire, god as king in heaven, etc.) were those of a bureaucratically administered state, no longer of tribal organization. Just like the shaman, the king in the cosmological empire performed the function of the link between the divine and the human, between the spiritual and the fleshy material; in the cosmological civilizations, from the Mesopotamian empires, whose consciousness was most compact and static in the sense of being resistant to evolutionary change (differentiation), through the more differentiated Egyptian dynasties, to the most differentiated Chinese kingdoms and empires, the king (or emperor), first of all, replicated the divine/ cosmic conservational order in the human world, hoping to conserve, or fix, i.e. stabilize, the internal equilibrium of the social or rather imperial organism against the disintegrating effects of the second law -- i.e. against its natural tendency to reach equilibrium with its environment; and secondly, he maintained human relationships with the gods (or Heaven in the more differentiated framework of the Chinese) in equilibrium (through sacrifice and divination; and in the later Chinese empire, through the maintenance of moral order; c.f. later) so that not only were the needs of existence of the members of the empire or kingdom (such as food supply through agriculture) satisfied just as in shamanistically maintained tribal orders, but the bureaucratic survival proper to these cosmological kingdoms was maintained as well. More on the divine conservational force of order in the next.

3. Let us here then briefly summarize the contemporary view on the formation of order through self-organization. This continues from the material meaning of life we have analyzed in the thermodynamic interpretation of history, and remember that there Fritjof Capra defines life or an organism in three key criteria (The Web of Life): pattern as autopoiesis ("the network pattern in which the function of each component is to participate in the production or transformation of other components in the network", p. 162), structure as dissipative structure, and process as (the non-conscious type of) cognition. To continue from this, "[a]ll living organism is characterized by continual flow and change in its metabolism [dissipation via autopoiesis], involving thousands of chemical reactions. Chemical and thermal equilibrium exists when all these processes come to a halt. In other words, an organism in equilibrium is a dead organism..." This equilibrium is identified by the ancients as evil. "Although very different from equilibrium, this state [far from equilibrium, of life, the good] is nevertheless stable over long periods of time [hence called internal equilibrium here], which means that, as in a whirlpool, the same overall structure is maintained in spite of the ongoing flow and change of components." (p. 181) In classical linear thermodynamics "[t]he system will always evolve toward a stationary state in which the generation of entropy (or disorder) is as small as possible. In other words, the system will minimize its fluxes, staying as close as possible to the equilibrium state. In this range the flow processes can be described by linear equations." Now non-linear thermodynamics tells that "[f]arther away from equilibrium, the fluxes are stronger, entropy production increases, and the system no longer tends toward equilibrium. On the contrary, it may encounter instabilities leading to new forms of order that move the system farther and farther away from the equilibrium state. In other words, far from equilibrium, dissipative structures may develop into forms of ever-increasing complexity." (Ibid.) This is self-organization, order-formation, the creative power within the general disintegrating thermodynamic flux. Of course the flux -- i.e. inflow of energy -- has to be present. "Dissipative structures in effect collapse energy-matter gradients. If the gradient were not replenished, the structures themselves would collapse. A cell deprived of nutrients dies." (Depew and Weber) "Far from equilibrium, the system's flow processes are interlinked through multiple feedback loops, and the corresponding mathematical equations are nonlinear. The farther a dissipative structure is from equilibrium, the greater is its complexity and the higher the degree of nonlinearity in the mathematical equations describing it.... [this is] the crucial link between nonequilibrium and nonlinearity..." (p. 182) "The linear equations of classical thermodynamics, Prigogine noted, can be analyzed in terms of point attractors. Whatever the system's initial conditions, it will be 'attracted' toward a stationary state of minimum entropy [production], as close to equilibrium as possible, and its behavior will be completely predictable... systems in the linear range tend to 'forget their initial conditions'... [But n]onlinear equations usually have more than one solutions; the higher the nonlinearity, the greater the number of solutions. This means that new situations may emerge at any moment. Mathematically speaking, the system encounters a bifurcation point in such a case, at which it may branch off into an entirely new state... In the nonlinear range initial conditions are no longer 'forgotten'. Moreover, Prigogine's theory shows that the behavior of a dissipative structure far from equilibrium [macroscopic order of the biospheric level] no longer follows any universal law [and certainly not the universal laws given since the beginning of the Universe like those for fermions and bosons] but is unique to the system." (Ibid.) This we have mentioned in the Synopsis. "Near equilibrium we find repetitive phenomena and universal laws. As we move away from equilibrium, we move from the universal to the unique, toward richness and variety." (Ibid.) The "indeterminacy at bifurcation points is one of two kinds of unpredictability in the theory of dissipative structures. The other kind, which is also present in chaos theory, is due to the highly nonlinear nature of the equations and exists even when there are no bifurcations." (p. 183) Now "chemical instabilities will not automatically appear far from equilibrium. They require the presence of catalytic loops, which brings the system to the point of instability through repeated self-amplifying feedback. These processes combine two different phenomena: chemical reactions and diffusion (the physical flow of molecules due to differences in concentration). Accordingly, the nonlinear equations describing them are called 'reaction-diffusion equations'." Now there are always feedback loops "in a self-organizing process, in which structures of increasing order emerge at successive bifurcation points." (p. 190 - 1) "A bifurcation point is a threshold of stability at which the dissipative structure may either break down or break through to one of several states of order. What exactly happens at this critical point depends on the system's previous history... [And t]his important role of the history of a dissipative structure at critical points of its further development, which Prigogine has observed even in the simple chemical oscillations, seems to be the physical origin of the connection between structure and history that is characteristic of all living systems. Living structure... is always a record of previous development." (p. 191) "Thus all deterministic description breaks down when a dissipative structure crosses the bifurcation point. Minute fluctuations in the environment will lead it to the choice of the branch it will follow. And... in a sense, it is those random fluctuations that lead to the emergence of new forms of order... Thus 'self-organization processes in far-from-equilibrium conditions correspond to a delicate interplay between chance and necessity, between fluctuations and deterministic laws." (p. 191 - 2) The formation of macroscopic complex order thus follows the causal sequence: nonlinear entropy production, bifurcation point, feedback loop, instability; after which the resulting loop needs only to acquire membrane boundary and self-replicative ability to be considered "life".

4. E.g. in the case of the Huron, the offense of wounding "was compensated with presents that varied in value according to the seriousness of the injury and the status of the person who had been attacked... There is no evidence that wounding as a result of deliberate assault was differentiated from accidental wounding. Wounds inflicted by one Huron on another as the result of a hunting accident were compensated in the same way as if they had been caused deliberately." (Trigger, ibid.,, p. 95)

5. The primordial meaning of "debt" can be gleaned from the Latin debeo. "Le sens de latin debeo parait résulter de la composition du terme en dē + habeō..." Its meaning is "having something which one holds of someone else" ("avoir quelque chose [qu'on tient] de quelqu'un": Benveniste, Le voc. des inst. Indo-Europ., vol. 1, p. 185). It does not mean "debt from borrowing" per se, as "on peut 'devoir' quelque chose sans l'avoir emprunté: ainsi le loyer d'une maison, qu'on 'doit' bien qu'il ne constitue pas la restitution d'une somme empruntée. En vertu de sa formation et de sa construction, debeo doit s'interpréter d'après la valeur qu'il tient du préfixe de, à savoir: 'pris sur, retiré à': donc 'tenir (habere) quelque chose qui est retiré (de) à quelqu'un... [Donc] debeo s'emploie dans des circonstances où l'on doit donner quelque chose qui revient à quelqu'un et qu'on détient soi-même, mais sans l'avoir emprunté littéralement... On emploie debere, par exemple, pour 'devoir la solde de la troupe', en parlant du chef, ou l'approvisionnement de blé à une ville." (p. 185 - 6) Similarly one who artificially increases his pleasure through injuries on someone else has something of this someone or of the cosmos in general which he must give back -- even forced to do so by the "law of nature" -- through equivalent injuries on himself: karmic retribution.