|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. Two Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial 2.D.1. The example of the Yijing Metaphysics of Sung Dynasty, China Chapter 4B ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

|

Scientific Enlightenment, Div. Two Book 2: Human Enlightenment of the First Axial 2.D.1. The example of the Yijing Metaphysics of Sung Dynasty, China Chapter 4B ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |

copyright © 2003, 2006 by Lawrence C. Chin. All rights reserved.

Thus if yang = 1 and ying = 2 -- meaning, e.g. that ying has intensity of spatiality 2 and yang 1 or that yang is more existent than ying by the measure 1 -- and the (spatial) intensity of the hexagrams thus carried by the solar periods is calculated in the corresponding table below, one can notice the rising and ebbing of existence in the manner of spatial directions, yearly seasons, and the hours of the day. (Again "period" is designated by 1 and "air" by 2 and the spatial intensity of the hexagrams by the sequence 12-11 or 10-10-9, etc. The cycle starts from Kun, North, as before.)

| [1] N 11m (1) 12-11 wint.sols. |

[2] 1am (2) 10-10-9 | [3] 12m (2) 10-9-10 | [4] 3am (1) 8-10 begin.spring |

[5] 1m (2) 9-9-9 | [6] 5am (2) 9-8-8 |

| [7] E 2m (1) 7-10 spri.equi. |

[8] 7am (2) 9-9-8 | [9] 3m (2) 9-8-8 | [10] 9am (1) 7-9 begin.sum. |

[11] 4m (2) 8-8-7 | [12] 11am (2) 8-7-7 |

| [13] S 5m (1) 6-7 sum.sols. |

[14] 1pm (2) 8-8-9 | [15] 6m (2) 8-9-9 | [16] 3pm (1) 10-8 begin.autum. |

[17] 7m (2) 9-9-10 | [18] 5pm (2) 9-10-10 |

| [19] W 8m (1) 11-8 autum.equi. |

[20] 7pm (2) 9-9-10 | [21] 9m (2) 9-10-10 | [22] 9pm (1) 11-9 beg.wint. |

[23] 10m (2) 10-10-11 | [24] 11pm (2) 10-11-11 |

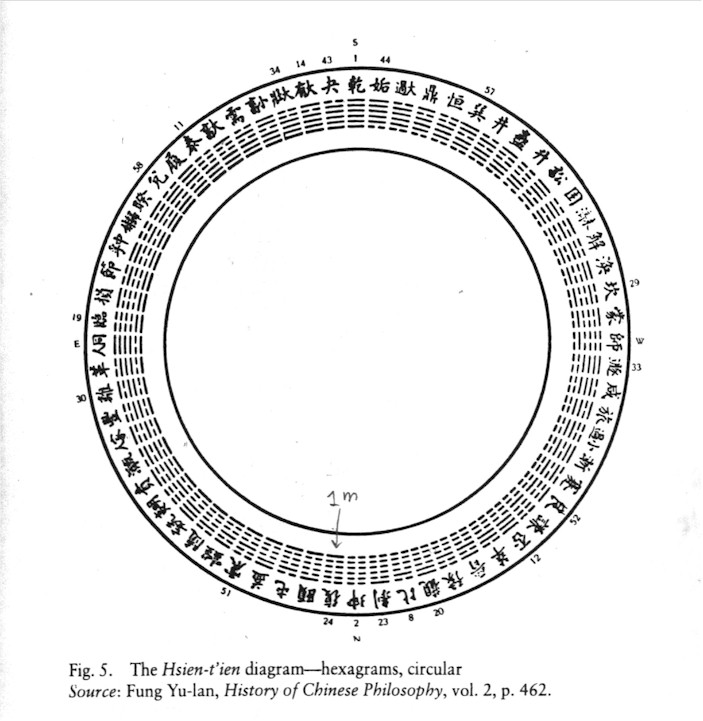

So from the 11th month until the 5th month the spatial intensity is falling, from 12th to 6th, yang rising; and from the 5th month to the 11th month the number is rising again: ying rising. Same with the cardinal directions and the hours of the day. The number in bold type indicates a sudden fluctuation of value, after every 7 hexagrams, that deviates from the trend of the surrounding. This is due to the changing of the trigrammic base after the trigrammic permutation on top has exhausted itself. Perhaps nature does contain such periodic fluctuations as well? Hou's circular hexagrammic correspondence with the yearly and hourly periods as presented here is evidently derived from the Guaqi of Han Dynasty which was the first of such attempts at hexagrammic correspondence with the terrestrial stems and calendrical units, etc. (John Henderson, The Development and Decline of Chinese Cosmology, p. 14.) For better reference the circular hexagrammic without the correspondences of hours and yearly periods:

Also to note is that the conservation formerly noticed of the trigrams across in the circle still holds with the hexagrams in this circular arrangement. With Yang = 1 and Ying = 2, let us look only at the first (I) and last (VIII) set. Qian = 6; Kun = 12. 6 + 12 = 18. The conserved number 18 is only double the original 9, as expected from the doubling of the trigrams into the hexagrams. Counterclock wise, Yang' 夬 = 7 and, opposing it, Buo 剝 = 11. 7 + 11 = 18. Then 7 + 11 = 18; 8 + 10 = 18;... til the last two, 大畜 8 + 萃 10 = 18 and 泰 9 + 否 9 = 18.

Again, the conservation of the "total quantity" of spatiality (and so inversely the quantity of existence) for every axis (now there are 32 of them) means that the cosmos is fundamentally symmetric, due to the conservational principle. The temporal and spatial stretch of the omphalos (the center of the cosmos, the source of being) into summer/winter and south/north, or into the beginning of spring/autumn and northeast/southwest, generates the symmetry that summer and south (or beginning of spring and northeast) are the mirror image of winter and north (or beginning of autumn and southwest), i.e. ying exchanged for yang and yang for ying. The beginning of spring/ 3am/ northeast, for example, is quantitatively represented by 2 hexagrams, first with Zhen as the base and Qian

as the top, the second with Li

as the base and Kun

as the top; the beginning of autumn/ 3pm/ southwest by the 2 hexagrams that are mirror image of the first two: first with Xun

as the base and Kun

as the top, the second with Kan

as the base and Qian

as the top. Any pair of hexagrams on the opposite ends would be like this. The cosmos as experienced is indeed like this: a circular set of binary oppositions (mirror images), summer solstice the mirror image of winter solstice, and, the cosmos being the repetition of this same structure of circular set from microscopic to macroscopic levels, from spatial to temporal repetitions, noon and south the mirror image of midnight and north. This representation of the cosmos by the circular hexagrammic structure is moreover quantitative, a size-up through numbers. This representation -- containing moreover the truth of existence, that spatiality is the inverse of existence -- works, as long as one sees the cosmos from the Middle Kingdom, just as the Ptolemy representation of the Universe works as long as one stays on Earth. If one goes to the southern hemisphere then the circular hexagrammic representation needs to be inverted. But if one leaves the Earth (i.e. transits to the structural perspective) then the representation will break down.

|

Fuxi's Square Diagram of the 64 hexagrams

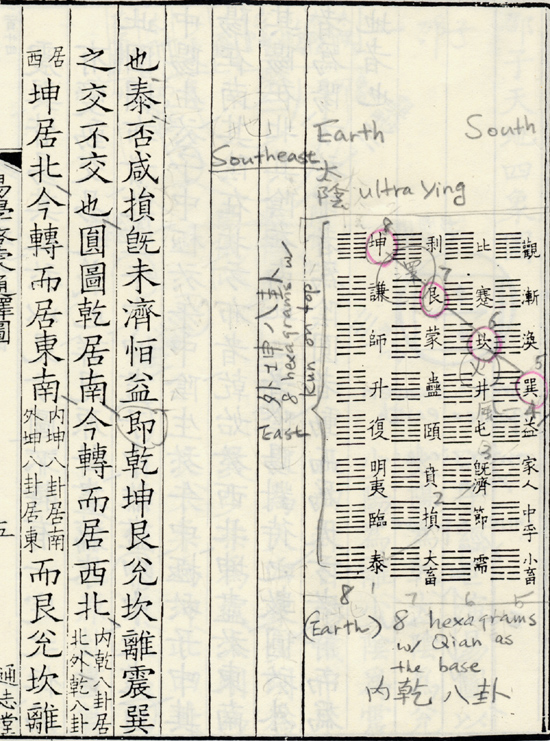

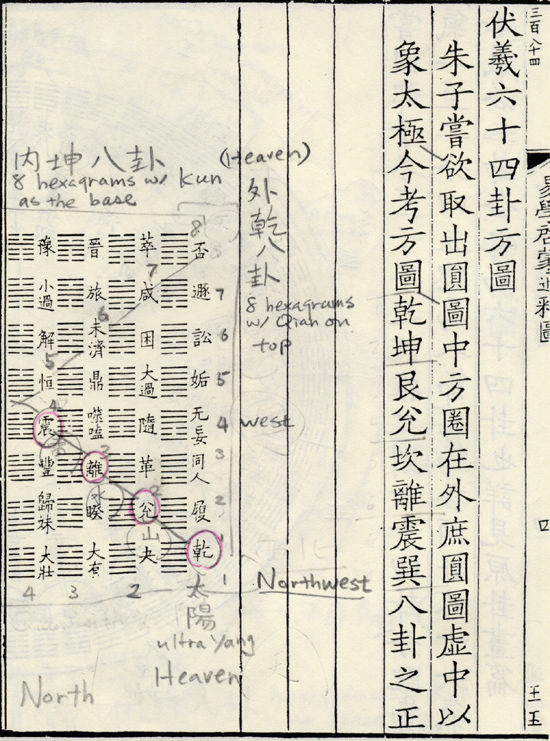

Zhu Zi... to represent Taiji. Now consider the square diagram. Qian (1), Kun (8), Gen (7), Dui (2), Kan (6), Li (3), Zhen (7), and Xun (5) are the orthodoxal of the 8 [tri]grams. |

What one can see is that these eight pivotal hexagrams, the doubling of the original eight trigrams, form the diagonal axis of the Square Diagram, from the upper left (southeast) to the lower right (northwest). The bottom-most row of the eight hexagrams corresponds to the first set of the eight hexagrams in the derivation, i.e. those having Qian as their base. Their numbering from 1 to 8 hence corresponds to the 1 through 8 of the first set of the eight in the derivation. (Note again, in the facsimile, the hexagram of Hsiau Chu [5 小畜] is misprinted. The base should be Qian.) The second lowest row then is the second set of the eight hexagrams in the derivation, with Dui

as the second from the right (or west). The third up is the third set, with Li

as the third. The fourth up is the fourth set, with Zhen

as the fourth. The fifth up is the fifth, with Xun

as the fifth. The sixth up is the sixth, with Kan

as the sixth. The seventh up is the seventh, with Gen

as the seventh. The top most row is the last set of eight hexagrams in the derivations, with Kun

as the last (the southeastern tip).

| Tai (1 泰), Fuo (8 否), Hsien (7 咸), Suen (2 損), Ziji (3 既濟), Weiji (6 未濟), Hen (5 恒), Yi (4 益) are the crossing/ non-crossing of [the 8 pivotal hexagrams]. |

What can be seen is that these eight hexagrams, as numbered 1 to 8 on the facsimile, form the diagonal axis from upper right (southwest) to the lower left (northeast). Tai (1) is the 8th of the first set of eight hexagrams in the derivation (the repetition of the eight trigrams on top of the trigram Qian; it being the last, and so the repetition of kun (8) on top of Qian (1)

). Suen (2) the 7th of the second set (the repetition of Gen (7)

on top of Dui (2)

). Ziji (3) the 6th of the third (the repetition of Kan (6)

on top of Li (3)

). Yi (4) the 5th of the fourth (the repetition of Xun (5)

on top of Zhen (4)

). Hen (5) the 4th of the fifth (the repetition of Zhen (4)

on top of Xun (5)

; note that now the process is reversing of the first 4, the up coming down and down up). Weiji (6) the 3rd of the sixth (Li (3)

on top of Kan (6)

). Hsien (7) the 2nd of the seventh (Dui (2)

on Gen (7)

). Fuo (8) the 1st of the eighth (Qian (1)

on top of Kun (8)

).

|

In the circle diagram Qian is situated at south, and now it changes to northwest. [The small print commentary, in quotation marks:] "The [eight] hexagrams with the Qian [trigram] as base [= 'the eight inner Qian hexagrams'] are situated at north, and the [eight] with the Qian [trigram] on top [= 'the eight outer Qian hexagrams'] at west." Kun [in the circle] is situated at north, but now changes to southeast. "The [eight] hexagrams with the Kun [trigram] as base [= 'the eight inner Kun hexagrams'] are situated at south, and the [eight] with the Kun [trigram] on top [= 'the eight outer Kun hexagrams'] at east." Gen, Dui, Kan, Li, Zhen, and Xun also change places in order to be seen in the Square Diagram. [All] do not have definite positioning but rather possess the principles of changing movements and cross-change. For detail, see the section on the original hexagrammic representation.

In the Circle Diagram, Qian exhausts itself at Wu3 (noon, 午); Kun exhausts itself at Zi3 (midnight, 子). Li |

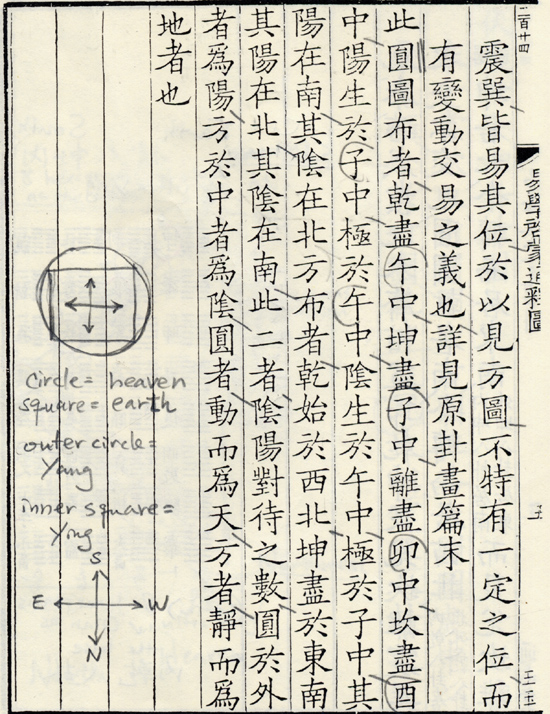

The enclosure of the square earth within the circular heaven will be seen to provide all the numerological orders of the cosmos in the Chinese functional perspective. Chuxi is to use it to justify the centrality (literally!) of 5 -- the "cosmological constant" -- in the Chinese perspective:

|

Question: Why do they both place 5 in the center [of River Picture and Luo Document]?

Answer: The beginning of all numbers is simply "One yin, one yang." The symbol of yang is the circle. If the circle's diameter is 1 its circumference is 3. The symbol of yin is the square. If the square's side is 1, its perimeter is 4. If a circumference is 3, and we take 1 as 1, thus by tripling this 1 yang [diameter] we make it 3. If a perimeter is 4, and we take 2 as 1, thus by doubling the 1 yin [side] we make it 2. This is what is meant by "Triple Heaven and double Earth."(65) 3 and 2 together then make 5. This is why the numbers of the River Chart and the Lo Text both place 5 at the center. [Introduction to the Study of the Classic of Change, trans. Joseph Adler] |

| ACADEMY | previous section | Table of Content | next section | GALLERY |